Editor’s note: This is part of Luke Babb’s “Reckoning” series. Today’s post includes descriptions of racist violence and racial trauma.

“Why,” the facilitator asked, “are you here today? What makes you want to do this work?”

I looked around the circle of my coworkers, more than a little wary of the answers, steeling myself for a fight. Uncovering systemic oppression is difficult, unpleasant, emotionally taxing work. Surely some of the people attending the Racial Equity Institute’s two-day course about systemic racism were there reluctantly, only participating as part of their job.

What I didn’t expect was the first response, from an older white man in a sweater and suit jacket. “I’m here because I believe we are all equal in the eyes of the Lord,” he said, looking around the meeting room. “And I believe our world should reflect that.”

As the question worked its way around the circle I sat, stunned, trying to figure out why that had taken me so off guard. Part of it, I knew, was the comfort and ease that he had in talking about his faith in the workplace, but it was more than that. Sitting there, thinking quickly and quietly as the question progressed toward me, I realized that one of the things I found surprising was seeing a Christian identify their faith as the reason for fighting against racism.

It took me some time to identify the reasons for my surprise. As I have continued to read and research, it has become clear to me that American racism has, at every step of its existence, relied upon a framework of Christianity. The laws that have enacted it, the groups that have enforced it, even the differences of race that it has rested upon, have been constructed and justified through Biblical passages. Not all American Christians are racist, but racism in America is inextricably Christian.

When this happened, I had already started this series about examining Christian influences on Paganism. Most things that American Pagans have inherited are manageable, or even useful in the right light. Racism is different. There is no place for racism in a Paganism divorced from Christian roots.

I believe that being Pagan, and uncoupling Paganism from the culture of Christianity, necessitates interrogating and divesting from the unscientific, ahistorical fiction of white supremacy. As I continue to look at racism in Pagan circles, I find borrowings and overlays of America’s specific and Christian construction of race, rather than anything truly sourced from the lore. These beliefs do not belong here, and are not based in the historical periods that reconstructionists study. But they are pervasive. The last 200 years have made them so much a part of American culture that identifying and cutting racism from our practices requires constant anti-racist action. It is not enough to identify racism as wrong – we must identify the injustices in our own theology, the imbalance in our communities, and work against them.

A believer can become antiracist while being Christian, because while Christianity has been used to justify racism, it has also provided a doctrine of equality and freedom that motivates people like my coworker. The opposite is not true. We cannot cease to be Christian while remaining racist. American racism is the child and lover of the American church, a byproduct and creator of its most damning doctrines and historical precedents, the clearest place its relationship with American democracy can be observed.

Let’s look at it.

Štefan Straka, “Čeština,” 1930 [Wikimedia Commons, public domain]

What we call race today did not exist in Antiquity. While people certainly could see differences in skin color, Ancient Greek and Roman scholars made it clear that what mattered was where people lived, not what they looked like. In fact, the science of the time was very clear that a person’s temperament, mental acuity, and physical ability depended on the climate where they grew up — people in the wetlands would be more sedate than people from the desert, for example. If a tribe came from a river valley, or a nation existed mostly in the desert, the people were expected to show the traits of their terrain. This gave the rich, city-living people who wrote the books a way to look down on the people living “over there.” These theories were never tied to bloodline, however. They couldn’t be. The migration of tribes and the ways that they mingled meant that the people described in, for instance, the Germania would have a substantially different demographic two or three generations down the line. Communities blended. People moved. The idea of the “other” was fluid, and there were many things more important to describing it than skin color.

As an aside — this is hard to tease out in modern translations, because the idea of race is so pervasive that editors have gone back and put it into the mouths of the ancients. My favorite way to get a look at it is in mythology. Many myths have different “groups” of gods, often from different places, that interact in less than pleasant ways. Still, I have yet to find a myth that blames even the worst kinds of enemy on some basic difference in “type.” The Aesir and the Jotnar intermarry, war, and posture in much the same way neighboring kingdoms might. The Olympians descend from and overthrow the Titans in a political coup without even the benefit of a separate bloodline. People look different, but many of the most dangerous monsters are from right next door, or from inside the family. The idea that there are different kinds of people separated by their origin and appearance starts to break down once it’s examined.

This is because the concept of race, as America understands it, was constructed in Jamestown in the 1680s, or, at least, that’s when it was written into law. The 1680s are the first time that the government used the words “white men” rather than “Englishmen” or “Christians” to define who had access to the rights and privileges of their new land. The idea of difference based on skin color had been fomenting since the 1400s, and had been used to justify atrocities against native populations throughout colonialism, but it had never before been written into law. This was the first of many deliberate choices America would make about race, and it was made for a specific reason. In England, Christians could not enslave other Christians. Defining slavery based on race allowed slave owners to evangelize to a captive population that could not return home. It was a law created in order to allow the spread of Christianity.

This required some mental gymnastics because, until that point, slave owners had been debating whether or not people of color were even capable of becoming Christian. Many slave owners believed in something called “hereditary heathenism,” an old European belief which argued that religion, like skin color, was passed down from parent to child. This meant that people who looked a certain way, and had non-Christian beliefs, were incapable of being Christian and therefore were free game for slavery. Once it became legal to enslave other Christians, the idea of hereditary heathenism faded away.

Or at least, hereditary heathenism fell out of mind until its latter-day resurrection as “metagenetics.” Coined by Stephen McNallen, founder of the Asatru Folk Assembly, in 1980, “metagenetics” is the pseudo-scientific argument that religions are passed through genes. It’s used as a logic for why only people with Northern European ancestry should be Heathens, and, like race, it is biological nonsense. All modern genetic studies have shown that there is more variety within a supposed “race” than across races. Being able to trace a bloodline back to a specific area does not guarantee that it will be genetically similar to the people in that area. There is no science to metagenetics. While it is, at this point, a well-established and often cited justification for modern Heathen racism, it is taken directly from Christianity – and specifically from the Christians that used it to subjugate pagan faiths.

Scientifically, nothing about the human body is indicative of race. It is the first great American export — a shifting fiction that defined race by what it was not and allowed people who looked like they had European ancestry to claim power. In Pagan terms, it was a modern myth, a powerful story that depended on the framework of Christianity to spread itself, and one that has been instrumental to the spread of Christianity and the the history of our nation. One defense of the South’s secession asked, “And above all, was it nothing that [black slaves] should be brought, by the relation of servitude, under the concienses and Christian zeal of a Christian people?” The justifications of slavery based on Biblical passages make up a considerable chunk of the arguments around the South’s secession. Firsthand accounts of Confederate soldiers make it very clear that, for many men in the Civil War, slavery was a holy cause worth dying for.

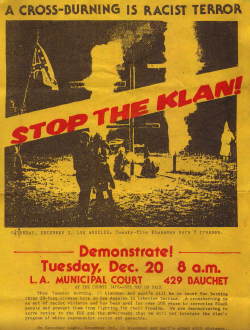

[Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

Those arguments didn’t go away after the war. They continued to be codified into law and built into the infrastructure of the country. Jim Crow laws were defended legislatively with Biblical arguments. Groups that rose up to subjugate newly freed black people did so in explicitly Christian ways. (The most obvious example of this is the KKK’s use of crosses to spread terror.) The pervasive split between White and Black Christian congregations also has its roots and modern enforcement in racism within the church. While the specifics of American chattel slavery have faded into history, the myth that allowed for its creation has been baked into the structures that make up America—our educational system, our transit systems, and especially our spirituality.

Knowing this history brings me to two conclusions. The first is that, if I want to achieve a real understanding of pre-Christian sources and live an authentically Pagan theology, I need to do the work of removing racist structures from my worldview. The difficulty there is that, as a white American, I am constantly complicit in the enactment and propagation of racism. In order to combat racism I need to be actively anti-racist, in my daily actions, in my work, and in my religion. That’s a lot of work and, frankly, it is sometimes overwhelming.

The second conclusion is that modern American Paganism, by the sheer fact of having been founded and grown in America, is also racist. For some of us, that’s not a surprising conclusion. My fellow Heathens have encountered virulent white supremacist versions of our faith. But the issue runs deeper than fringe elements who use our gods as a decorative cover for their hatred. The ways we read our texts, the ways we structure our communities, the services we offer those communities, and the theology that underpins our Paganism are all necessarily infected by the American myth of race.

There is a reason so many Pagan groups are majority white. There is a reason we so often come from affluent and educated communities. There is a reason our many theologies are founded on similar texts, and have reached certain conclusions. There is a reason that our communities, when challenged to grow by people of color, so often fail instead.

American Paganism, by sheer fact of being American, is racist. American racism, in its history and modern expression, is Christian. What sort of Paganism might we create, who might we be, if we committed to fighting it?

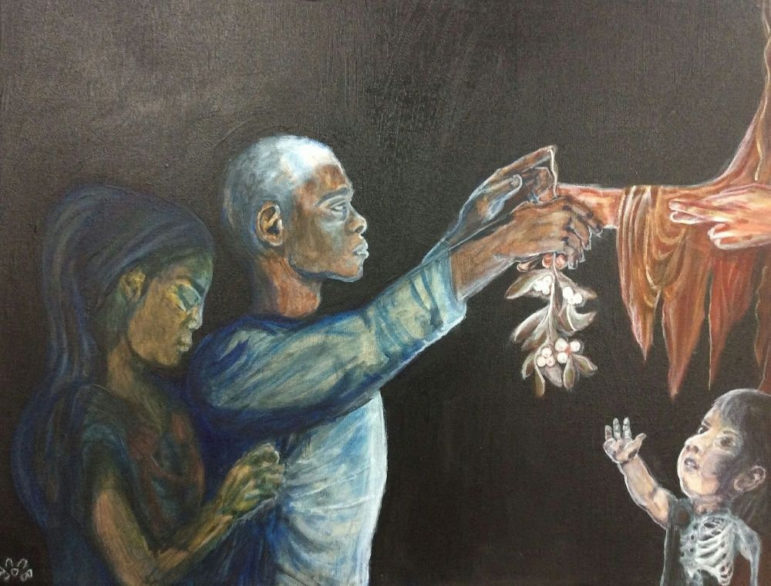

Bat Collazo, “Frigga’s First Sorrow” [courtesy]

This is a difficult proposal. Racism is built into American culture to the point that it is almost invisible. Investigating it in ourselves is emotionally taxing work that often feels dangerous, and requires us to put our truths on the line for reevaluation. It is a massive project that has no clear starting place, just an endless parade of movies, books, and podcasts teasing apart some new area of culture to reveal the underpinnings of racism. More difficult is that much of the good work is being done within the Christian church, examining its history and working toward reconciliation. Bringing that work into a non-Christian setting often feels like compounding the problem.

That doesn’t change the fact that it must be done.

I continue to think of the man, sitting in a two day class, about to get down into the weeds of anti-racist work, who found strength and joy in doing so through his faith. There are ways for Pagans to ground anti-racist action in our theology as well. I’ll focus on some of those next month. But for now, there is work to do. That work can and must include self-examination, but with all of this introspection, learning, and theological discussion we also have to act and, most importantly, to listen. I am white, and I live in America, and at the end of the day the difficulty here is in how it makes me feel – not in an experience of oppression. Starting to fight back against racist systems means listening to those most affected. It means centering their experience, believing their stories, and offering the help they ask for. Everything starts there.

For those interested in learning more about this history, I suggest the “Seeing White” series on Scene On radio and Jemar Tisby’s book “The Color of Compromise.” There is also this video from Dr. Robin DiAngelo, which examines how white people can begin doing anti-racist work, and which was funded by the United Methodist Church.

Stay tuned for next month’s reckoning.

The Wild Hunt always welcomes submissions for our weekend section. Please send queries or completed pieces to eric@wildhunt.org.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.