[Editor’s note: This column is intended to be the first part in a series of columns investigating some of the underexamined relationships between American Christianity and American Paganism.]

The first time I felt a god’s presence was in church.

I was young, still – middle school young, driven here by my parents young – and in my small town understanding this was what people meant by “religion.” I had a vague understanding that the Catholic kids down the street did something different, somehow, but at its base it was the same. Bible school, a song, a sermon, offerings, another song, and then you were done. Probably, I thought to myself, the Catholics had different songs, but all the songs went to the same place, so that didn’t seem important.

That was the shape of my Sundays, from early breakfast through late lunch, for my entire childhood. For the most part it was fine. I liked singing, liked the work of a cappella hymns led from the front by an off-key baritone who refused to take the soprano section’s hint. I liked the people at church, with their thin-skinned hands and sacks of spare zucchinis. Occasionally I even liked the sermons, if only because they gave me time to dream. Intentionally or not, as the pastor held forth my mind would wander, coming back only occasionally to check on the thread of his argument before vaulting off to Westchester, or Baker Street, or wherever my fantasy life took me that day.

I don’t think those times were meditative, or even astral experiences, at least no more than any flight of imagination is. But they do explain why I have no memory of what exactly was happening on this particular day in church. I don’t recall the sermon being especially interesting, or being moved by a particular song. If anything, I remember being miserable, the way teenagers are always miserable, and feeling very isolated, although that might be my urge to situate the experience in a story, to give it more depth.

What I know is that, as I was sitting in the bare wooden pew, I felt the unmistakable weight and heat of a hug. It was simple – two arms circling my chest, as if someone was sitting directly behind me. There was nothing else – no heat of a body, no visible change in the room, no smell – and that made it even more strange to me. The denomination I was raised in had no room for mystical experience, no tradition of miracles after those written in the Bible. When the lay leader talked about a “personal relationship with Jesus,” that was a metaphor, a way to talk about reading the Bible and drawing your own conclusions about its content, though those conclusions were always mediated by the teachings of the church.

The arms lingered for a few minutes, still warm, still inexplicable, before the sensation faded. I pulled my mother aside after the service to ask about it, in that hushed and uncomfortable voice that children use when they ask, “Is this normal? Is there something wrong with me?”

She looked a little uncomfortable, and then shrugged. “You were probably just cold,” she said, giving me a warmer, more encompassing hug. “Let’s get you something to eat.”

And that was that.

This story sat for a long time in a small folder in the warehouse of my brain that might be labeled Things That Were Real. Experiences I have had that I can’t explain, cannot even link to other areas of thought, are filed there until I have other uses for them. I reference them from time to time, test them out. Does this make sense yet? If not, back into the file it goes. If, on the other hand, something finally clicks into place, it is often the missing piece, the context that allows synapses to fire and connections to slide into place. These are the pieces that make the world grander than I would otherwise understand it to be.

This story sat for a decade, unremarked and half remembered, until I was sitting in a Pagan discussion group and the conversation, as it inevitably does in certain circles, swang back around to Christianity.

“It’s my experience,” said one member of the group, “that the gods of the Christians are all dead. What they are worshipping now are egregores, thought forms that they’ve created. The original deities – El, Baal – they’re as dead as gods get.”

With no prompting, the memory of that morning came back to me, the inexplicable arms that came unprompted, asking for nothing in return. I told the story hesitantly, still unsure in my own theology and knowing it was unwise to say something positive about the Christian god in this space.

The member frowned, thoughtful, and then shook his head. “Probably just a parasite,” he said, and moved the conversation on.

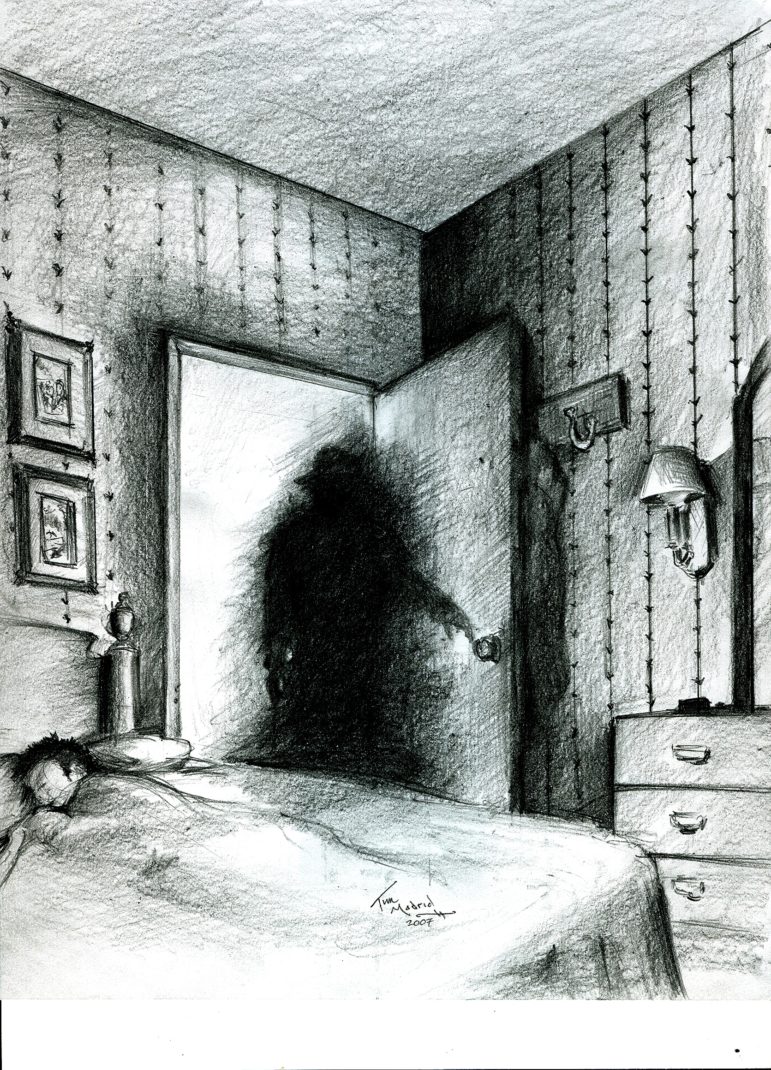

Shadow People [Timitzer, Wikimedia Commons]

Here are some things I have experienced in the Pagan community:

- Many of us are ex-Christians.

- Many of us have had incredibly hurtful interactions with the Christian church.

- Many of us are extremely fucking rude about the Christian faith.

In case my editor has edited the line above, let me make it clear that it originally included some expletives.

In my relatively short time as a Pagan, I have encountered some truly hateful rhetoric pointed at the Christian god(s) and their followers. Christians are deluded. Their belief gives them nothing. Their gods are dead, evil, pulling the wool over their eyes. They are being used for the spiritual gain of false gods. They are being used for the financial and emotional gain of people, and there are no spirits involved at all. And as a consequence of this rhetoric, Pagans who work with Jesus and his father are tacitly uninvited from events or loudly decried as everything from fools to traitors.

In short, I have heard all of the things that the Christians tend to say about us.

The crux of it, for me, is a conflation of the church, which I experience as a man-made and largely political organization, with the deities themselves. While I don’t run with that crowd anymore, the Christian pantheon is certainly no more difficult or uncomfortable than any of the gods I currently worship. Their dad’s a jealous type, but the kid is on record as being an all-around decent guy, with a lot of good things to say. They’ve got whole books about them, more than most other pantheons get, and by and large they’re good books. (The ones written by that guy from Tarsus are maybe the exception.)

It’s the church, the organization that has built up around people who believe in those deities and now enforces its interpretation of their words, that most of us have a problem with. It has told us we are hateful, broken things, taken away our liberties, abused us with the knowledge and consent of its elders. Individuals have hurt us in its name, and continue to do so at seemingly every turn. There are plenty of reasons for a modern Pagan to dislike the church, and the church is inescapable.

Sun and Cross and Shadow [Magnus Hagdorn, Wikimedia Commons]

I was in my last year of college when I first met someone who didn’t know anything about Christianity.

She was in my “Women in Medieval and Early Modern English” class, which pretty much sums up the problem. I don’t remember what we were reading, specifically, and it really doesn’t matter; anything that comes out of England between 1066 and 1859 is likely to feature Christianity. When it became clear that she had no context, not even a basic understanding of the Christmas story, the classroom ground to a halt. Even the teacher was taken by surprise. How could we start talking about medieval ideals of virginity if she didn’t know who Mary was?

I remember that the weirdest part, the part that really threw me at the time, was that she was from Missouri. Growing up in America, in my neighborhood of America, without growing up under the background radiation of Christianity seemed impossible. I wasn’t sure I believed it could be done. Not without some careful planning and lucky happenstance, anyway, on her parents’ part if not her own.

Looking back, I point to this as the first moment in which I was able to distinguish the church from its mythology. Because I believe that I was right. It is impossible to live in America without feeling the effects of the American church, even if one is somehow ignorant of its theology. It is baked into our political landscape, as it always has been, as it is baked into the physical landscapes of even our smallest towns. Our laws have been made, enforced, and interpreted by Christians, often with the funding and directive of the church. Our morals, learned from family and taught in schools, derive from its specific interpretations of holy texts. Even if we have never heard of Nazareth, our culture has the American church baked into every aspect.

I believe that, as Americans, we carry that legacy with us in ways that are pervasive and unexamined, too much a part of how we understand the world to be noticeable as the emanations of one common source. As converts, many of us carry it even deeper still, in the bedrock foundations that make up our personalities, the experiences that shaped us as children.

Those experiences are, in some ways, immovable. I can no more forget my childhood than my mother, and losing either memory would make me a different person than I am. But there are other ways in which I can tease out individual effects and examine them, deciding whether to incorporate them into my current worldview or set them aside as no longer useful. One of those ways, for me, is a whole lot of therapy. Another is Pagan theology.

These are huge claims, and it will take me more than one essay to argue for them. Let me give an example, just to start out.

[Gardenermd, Wikimedia Commons]

I remember holding hands and crying.

I was young – all of the stories of my time in church start that way. I was young, and newly baptised. In my family’s denomination, baptism is an opt-in oath, a sacrament that is held until the age of consent. Jesus may have died to cleanse the sins of man, but I was taught that I needed to accept that gift and allow him to cleanse my wickedness. If I died before that, I’d end up in hell. While I wasn’t entirely sure what I believed, I knew that the idea of spending an eternity in pain and away from my family scared me enough to steal my sleep.

I got baptised. And when I was dried off and brought out to the congregation, they were singing with joy, and I was sobbing, shaking with relief. There was no more threat of hell. I was saved.

“Now, I am your brother,” said the man on my right. He was a longstanding member of the congregation, and I could tell he was confused at my reaction, not sure what to do to console me.

“Yes,” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say. I loved that congregation, the familiarity of them, the repeated shapes of strangers that I never really got to know. I wanted him to feel better. I didn’t really understand why I was crying, either.

I have made very few oaths in my life. This was my first.

Oaths are important for a Heathen. Sae Lokason has done an excellent job researching the history and connotations of why, but the theology is fairly simple. Taking an oath binds a person’s wyrd, their fate, to the fulfillment of a promise. It is a spiritual and magical contract, a guarantee signed with fate as collateral. Breaking an oath leaves a person liable, payment due to the gods themselves as well as to the beneficiary of the broken promise. That payment isn’t always pretty.

This is the theology that I used when I first considered my baptism from a Pagan lens. For reasons of my own, I did consider the baptism to have been an oath, the kind that I now consider binding – a promise to follow one god, and only that god, until my death. Depending on my mood and my philosophical bent, I wandered between two conclusions, when I thought that through. Either the oath, made too young and in bad faith, had no real hold on me, or I had broken it.

Other Pagans offered their advice, their own ways of paying off the debt that a broken oath incurs. I gathered rituals, repayments, tithes, and turned them over in my hands as I considered my options. When an oath is broken, payment is set by the person to whom the oath was owed. What value might that god place on the loss of my soul? Would it be something that I was willing to pay?

Moreover, would it make a difference? As I researched, I realized that in the theology of my parents’ denomination, baptism is not a final salvation. It must be followed up by a life of continual faith. Without that, they consider it void, an open door that has been rejected. This meant that the theology still holding me accountable was my own. The voice in the back of my head, repeating “this was real,” is only me.

I have come to believe that even if I were to pay schuld, a compensation for failure to maintain the oath, of some sort, it would not actually loosen the connection I still feel to that god. Wyrd is not the work of a moment. It is the building of a relationship: the long acquaintance, the eventual separation. My wyrd will always be colored by my time in the church and, for me, that feels almost freeing. Rather than panicking at being held by an inescapable debt, I am able to remember the good times, as well as the bad, and to search for lessons that I might otherwise have missed.

This story is both an example and a parable. Examining baptism through my Heathen theology has allowed me to examine and set aside a debt while honoring a more important connection – all of that is true. But just as my wyrd will forever be tied to my childhood relationship with Jesus, Paganism’s history will forever be tied to the history of the church. It is only through examining that history, recognizing those influences, and comparing them to our own theologies that we can start to come to terms with where we are and identify a place to move toward.

I hope to do some of that work over the next few months.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.