In yesterday’s post, I discussed the state of the publishing industry with respect to Barnes & Noble’s recent unimpressive fiscal announcements. How would the disappearance of the last remaining large-scale, traditional bookstore affect the metaphysical book industry? After speaking with two industry experts, the answer seems conclusive. A Barnes & Noble collapse, while not at all preferable, would not permanently damage either company. Llewellyn and the Phoenix & Dragon Bookstore both maintain flexible, diverse, customer-driven business structures that are adaptable in this evolving marketplace.

Photo Courtesy of Elysia Gallo, Llewellyn

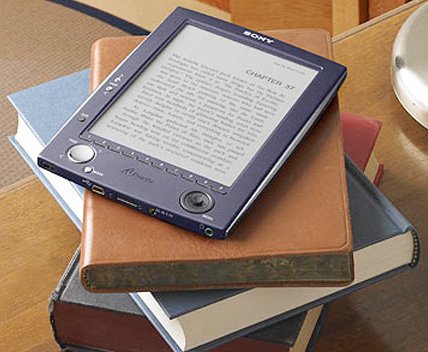

Will Barnes & Noble go the same way as Borders? Only time will tell. The industry is still changing and evolving. To date, there are many factors that have contributed to the upheaval including increased competition, changing consumer behavior, and the diversification of the product. There are paper books, audio books and eBooks in multiple formats. There are books published by the “big six,” by independent publishers, and most recently, by the authors themselves.

Self-publishing has become one of the hottest trends in the marketplace. Several weeks ago I interviewed New York Times best-selling author John Matthews, who had just announced the launch of his new self-publishing venture Mythwood Books. After years of negotiating the traditional publishing world, Matthews has chosen to “go it alone” in order to earn a greater percentage of the revenue and to maintain creative integrity over his work.

As I reported in that article, approximately 43% (or 148,424) of all published books in 2011 were self-published. Bowker Books in Print reports the 2012 figure to be well-over 235,000 titles.The number continues to grow.

Cara Schultz

First-time author Cara Schultz chose to self-publish after an uncomfortable encounter with a traditional publisher. She explains:

The security, expertise, and wider distribution offered by publishers were attractive, but in the end the loss of control over my content and brand weighed too heavily… The publisher wanted to add and subtract products featured in my book based on advertising and marketing partnerships with companies. I wanted to only feature products I own, use and recommend based on performance.

Virginia Chandler

Virginia Chandler, author of fantasy fiction novels, and Christine Hoff Kraemer, Patheos Pagan Channel’s managing editor, also made a similar choice. Chandler’s first two books were published by Double Dragon Publishing, who she describes as “very supportive.” However, she “craved more control” over her end product and has now turned to Amazon’s Create Space. Kraemer published her first books through a traditional academic publisher but turned to the more progressive Patheos Press for her most recent work, Seeking the Mysteries: A Introduction to Pagan Theologies. “The royalty percentage [is] much higher,” she says.

In response to the Matthews interview, author Donald Michael Kraig posed a poignant question to those who do choose to self-publish:

Self-publishing replaces everything the publisher did, including promotion, advertising, marketing, etc. Publishers have distributors and can get their books into bookstores and chains. How will you, the self-publisher, accomplish this?

Christine Hoff Kraemer

All three of authors had the same response. Shultz said, “Publishing houses say they will help market your book, but … they really won’t.” Chandler agreed saying, “Unless you are JK Rowling, Dan Brown, or a guaranteed million dollar selling author, you are going to be doing all of the promotional legwork.” Kraemer added, “Some publishers still do limited marketing for you, although this is becoming more rare.”

So how does their choice to “go it alone” affect the traditional book industry players? EBooks nearly eliminate the need for a publisher, distributor and brick-and-mortar store. Everything is done digitally. Phoenix & Dragon had already lost 15% of its sales to Amazon even before the popularity of eBooks. Self-publishing only exacerbates the problem.

Many self-published authors, like Kraemer, have turned to print-on-demand publishing services. These companies, such as Lulu.com, bridge the gap between a traditional publisher and full self-publishing. With print-on-demand, the author can offer a tangible product which broadens the potential readership and increases the likelihood of seeing their work on a store shelf.

However, it is not quite that simple. When I asked Candace Apple about the growth in self-publishing, she simple stated, “It makes life crazy.” Phoenix & Dragon employs a full-time book buyer who evaluates every book sold. This screening process becomes more strenuous with self-published products. In such cases, Apple can’t rely on a publisher’s reputation in order to pre-qualify a book’s content. Her buyer must carefully screen every self-published book. That takes time.

In addition, the cost is prohibitive. As Apple explains, self-published authors do not offer wholesale discounts and large inventories. Apple must pay the full cover price plus shipping for every book purchased.

With that said, Apple believes in supporting community and will showcase local self-published authors. “I enjoy finding the gems,” she told me. Fortunately for the self-published Pagan author, the independently-owned metaphysical bookstores have that flexibility. The big chains, like Barnes & Noble, don’t. Going forward, Apple hopes that Amazon’s new distribution processes will alleviate some of the headaches associated with selling the self-published book.

What about Llewellyn? How is it handling the increase in self-published material? Bill Krause said:

There is no denying it has never been easier to self-publish and would-be authors may choose this path rather than submitting a manuscript to a traditional publisher for consideration. We can’t change this, so we have to figure out how to work with it. We have picked up some authors who were originally self-published and sold them to the trade quite successfully. In some cases we had them write new books, in other cases we had them rework their original. In all cases, it’s based on the content of the work.

He continued on to say:

The number of self-published books that find success is extremely small. Unless the author has some industry knowledge and also happens to be a tireless marketer/promoter while also being a strong writer, editor and designer (or willing to pay for this assistance), it’s very difficult to find success.

David Salisbury

Author David Salisbury echoed this sentiment saying:

My books so far have all gone through the traditional publishing process. It made the most sense for me to go that route for all the practical reasons. I love writing but hate doing everything else that goes along with putting a book out (editing, marketing, pitching etc.). I felt better handing my work over to professionals who I trust more than myself to complete a nice polished product

Crystal Blanton

Crystal Blanton, author and Wild Hunt Columnist, also chose the traditional route. She said:

All three of my books are published through Immanion/Megalithic Press….I was looking for a partner in the process of working on my book. I chose to publish with a small press because I wanted the support of a publisher yet the creative freedom that a smaller press like Immanion could provide.

But what about that great promise of 70% revenue on every self-published book sold versus the 10-15% from a traditional publisher? Krause said, “70% of what? To be another face in the crowd with no marketing budget.” He reiterated the importance of the relationship that Llewellyn forms with its authors. This relationship along with its professional services can be invaluable over the long run – making up for that 55-60% revenue difference.

By Jorghex (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons

As for the mega book seller, don’t count Barnes & Noble out just yet. According to some analysts, Barnes & Noble is now in a golden position to thrive in one specific area –book selling. It has the brand name, the resources, the real estate and industry clout. The only question is: can it adapt to the changing climate, find a way to work with the growing population of self-published authors and compete with Amazon? If it does, it will only be good news for Llewellyn, specialty stores like Phoenix & Dragon and many others. If it doesn’t, we can all reminisce about our glory days getting lost in a book superstore.

Full Unedited Comments from authors:

Cara Schultz

Virginia Chandler

Christine Hoff Kraemer

Crystal Blanton

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Correction: I published Seeking the Mystery through an independent press (Patheos Press) that does only e-books and limited print on demand — I worked with an editorial team, so it wasn’t self-published. I wouldn’t call Patheos Press a “traditional” publisher, though, for the reasons stated in my full remarks, which you’ve already linked to. 🙂

This is me and the above comment can be deleted.

This is P. Sufenas Virius Lupus…still having trouble with Disqus.

As Apple explains, self-published authors do not offer wholesale discounts and large inventories. Apple must pay the full cover price plus shipping for every book purchased.

Has Ms. Apple actually checked with self-published authors on this? I have always offered the full range of Red Lotus Library books to independent booksellers and pagan shops at 40% off, the usual wholesale price, so that they can actually make a profit on selling them. It’s still hard to find bookstores that will stock the titles, of course, but many of us are doing our parts to make it easier and profitable for the independents.

There are definite advantages to going your own way. The devotional and fiction anthologies we publish through Bibliotheca Alexandrina are far too specialized for any mainstream publisher; it’s doubtful that even Llewellyn would take a chance on them. But we love what we do, and doing it on our own affords us full control of the content and final product. It’s hard work, but immensely satisfying.

I’ve bought a few of those and they’re spectacular. Thanks for all the work that obviously goes into them.

Could you give a website please? I pulled up what I thought was your site but it is dedicated to Egyptian Arabic content. Was that the correct site?

http://neosalexandria.org/bibliotheca-alexandrina/current-titles/

Thank you! Very different site from what I originally found.

(This is coming from someone who studies Publishing and just got done being an intern at a The Midwest Writer’s Conference)

The problem with Self-Publishing is that people don’t realize this is a new medium, so it requires new strategies for promotion and being noticed. People can’t be a noticeable force if they aren’t connected to the community and don’t already have a platform of other publications to stand on. Anything from a website with their own original content, prior books that people know and respect to something as simple as twitter or facebook updates that, even if we don’t think of them thusly, do count as publications. That’s the online world, and if a person has no presence in the online world it’s going to be very hard for them to make money online. It’s perhaps unfortunate, but it’s true. A writer’s best advertiser is that self-same writer, and anyone connected to the author through facebook/twitter/tumblr, or whatever the new site is in five/ten/fifteen years.

THAT BEING SAID, this advice applies more to “Mainstream” fiction (whatever the hell that is) and other publications where the market can come from anywhere. More and more rapidly, the pagan community is becoming more tech-savvy, and it’s possible that going digital publishing may be a good way for us to go. Much as I love the smell of a pagan’s book from a used bookstore or my local library (they always smell like a barrage of incense), the dissolution of information about all of the variations of paganism is going to be much easier if I can google a book on Solitary Reconstructionist Heathenry than if I have to wait for it to appear at my Books-A-Million, and the use of hyperlinks and author websites makes it much easier to find and build a community when there may not be one in my hometown.

However, there are a LOT of pagans who find their stuff from a bookstore. So many Teenage Wiccans exist because almost every bookstore has a copy of “Wicca for the Solitary Practitioner”, and that’s one of their few pagan books. Whether children would keep being able to access good books when they may not have access to credit cards is a question that is entirely dependant on internet piracy and how much online access to media is monitored by parents.

BUT, (and my gods, this really ought to be a blog post) a problem with self-publishing is that there’s no vetting process, and people may get access to a book without realizing that the publisher hasn’t done their homework. This could be problematic if people start getting ideas they shouldn’t, doing things they shouldn’t and being involved with the wrong groups of people or taking risks with their religious lives/souls/what not because the “How to do Wiccan Sex Magic” was only $2.99 and “Reconstructions of Buckland’s Book of Shadows for the New Millennia” was $4.99.

Although, the latter is also true of a great deal of mainstream publishing as well–both Llewellyn and Weiser publish things that have not been copyedited very well, and both also publish things that have not and never will be fact-checked. The amount of mainstream published Celtic claptrap and craptrap is astonishingly high, for example, and yet no one at those publishers ever bothers to try and check on even the most basic of matters in this regard far more often than they do; and if they do, it’s usually because the author is well-informed to begin with, and thus still no checking has gone on. There is just as much dangerous (as in “erroneous and thus leading to people having ideas they shouldn’t”) material out there with the imprimatur of the non-self-published book industry as there is good material; likewise with self-published things.

This, seriously. The idea that you can go by “publisher reputation” is kind of laughable with some of the clunkers Llewellyn has put out through the years (I think I could rest my case with “Witta” and its infamous Irish potato goddess alone). Self-publishing isn’t any worse when it comes to mangling facts. Mangling grammar, perhaps, but not mangling facts.

Some academic publishers don’t even do copyediting any longer, though–it’s too expensive and time-consuming in a process that is already overly both, and thus they just assume (and/or hope) that their author has done it adequately. Alas, that’s not always true, and it’s not always on harmless matters…

Ugh, that explains the uptick in really obvious, easy-to-catch goofs I’ve been seeing all over lately (one even had an egregious misspelling in the beginning of the second paragraph on the FIRST PAGE, fercryinoutloud). I just thought it was me.

I can attest to the truth of this — some of the academic copyediting I’ve experienced has actually introduced grammatical errors into my work.

What I’ve found on Lulu is a wide variety of quality. Some of the books I found there were gems; but others were banal, filled with poor grammar, or simply rip-offs of information that is easily obtainable elsewhere. If anyone knows of a site that helps a person navigate through the chaff of self-publishing, please let me know. Thanks.

Was going to comment with this on the B&N post but after reading Ms. Apple’s comments about self-pubbed books it applies even more here: I stopped going to brick-and-mortar Pagan shops because the range is almost always so astonishingly narrow. Wicca, Wicca, oh, look, more Wicca (and not even obscure Wicca much of the time, either, just crescent moons as far as the eye can see with a few by Weiser thrown in for variety), an Egyptian section with two new-age books and everything else by Budge, a Norse section with more crescent moons and the Blum set… well, you get the picture. “Metaphysical” stores that aren’t outright Pagan are often even worse– I’ve been in some where I couldn’t even find books on Wicca, let alone anything less common that’s Pagan. I found that if you’re not Wiccan or perhaps a Druid– or a CM, at some stores– there’s not a lot there for you. For me, the only reason to make what’s often a long trip to a store with limited hours (and that’s if they’re regular at all– I tried no less than three times to go to one Pagan store that was never open when it said on the sign that it would be, before I finally just gave up on it) and even more limited parking is to see works I never would have run into browsing Amazon– but if the store’s idea of “Pagan” is limited to Wicca and you’re not Wiccan, why bother?

There was, however, one store that broke all those rules, and I will forever miss it. It took a chance on small publishers and self-pubbed books way before the dawn of the internet and had books so obscure I’ve never seen them anywhere else since– and better still, had them on any New Age, occult, or Pagan-adjacent topic you could possibly imagine. That store was a treasure of a resource and an example of what an indy bookstore could be, and I spent hundreds in there (and ate lots of ramen because of it :). Was so sad to return to that city a couple of years ago to find that it had become another generic new-age shop with no Pagan books in sight because the owner died and his son thought that would be a better business model. Apparently the books went to a landfill. I still mourn its loss every time I’m up there.