NEW YORK – Long before it was commonplace for modern-day Pagans to participate in large-scale public rituals, there was the “Witch-In.” The event – a gathering of Witches, Wiccans, and other magical practitioners – was held in New York City’s Central Park on October 31st, 1970.

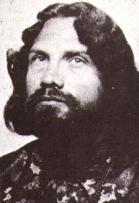

Leo Martello – 1970 Witch-In, Central Park, NYC [courtesy]

It drew over a thousand attendees, who danced, sang, and proclaimed their devotion to the goddess at a time when Witchcraft was still taboo and not as well-tolerated as it is today. A spiritual success and a landmark legal victory for Pagans when the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation granted a permit for the event, the “Witch-In” was the vision of an oft-forgotten trailblazer whose legacy has never been fully explored.

Dr. Leo Louis Martello was a Witch and gay rights activist who figured prominently in the early New York City Pagan community. Also an author, lecturer, psychic, hypnotist, and graphologist, he claimed to have descended from a long line of streghe – Italian Witches – who hailed from Sicily and passed down their magical customs strictly from one generation to the next.

Martello identified as a priest of the Old Religion; among its pre-Christian roots was the Sikelian* goddess to whom he paid homage and whose name, according to certain practitioners, remains a closely guarded secret. But neither secrecy nor an aura of mystery defined Martello’s life. He was, by all accounts, a vocal activist passionate about gay rights, feminism, and the evolution of the modern Pagan movement.

“As a gay man, Leo knew he had to live a closeted life […] or come out, but come out with an alternative lifestyle, and that meant an alternative religion, too,” said Peter Levenda, a friend of Martello’s and the author of numerous books, including Unholy Alliance: A History of Nazi Involvement with the Occult. “Paganism accommodated that need and gave him a safe space, as we would say now.”

Levenda pointed out that in the 1960s and 1970s, not all covens were open to homosexuality.

“It was difficult for gay men and women to belong to covens that were largely straight due to the god and goddess motif that governed the rituals, which seemed based on a strict male/female polarity,” he explained. “A gay coven could still respect the idea of polarity and gender but in a more nuanced and sophisticated way.”

A fierce opponent of discrimination, Martello quickly sought to remedy the problem. Following the Stonewall riots, he became a member of the Gay Liberation Front and later a founder of the Gay Activist Alliance, for which he authored a frequent column called “The Gay Witch.” He also founded the Witches International Craft Associates (WICA) and the Witches Anti-Defamation League, campaigning for the rights of Witches everywhere.

“Leo knew that normative sexuality was not the universal that many in the movement thought it was,” said Levenda, who notes that Martello’s insights were inclusive of religious history beyond the Judeo-Christian construct.

“There is a long tradition in Pagan history of transvestism, of eunuchs, sacred prostitution, multiple genders, and of homosexuality in priesthoods from Asia to Mesopotamia to ancient Europe. Obviously, there were homosexuals in the world long before Christianity was born and in many areas of the planet where Christian missionaries were slow to arrive. Thus, there had been a place for homosexuals (and other LGBTQIA+ individuals) in religious rituals, religious organizations, oracles, shamans, and the like. Paganism – and especially Wicca, which allowed everyone to become a practitioner as well as a devotee or follower – was Leo’s natural element.”

Early on, Martello recognized the need for a Pagan tradition that would respect and empower gay men, and it was in the late 1970s that his friend and fellow Witch, Eddie Buczynski, founded the Minoan Brotherhood.

According to its website, The Minoan Brotherhood is “a men’s initiatory tradition of the Craft celebrating Life, Men Loving Men, and Magic in a primarily Cretan context, also including some Aegean and Ancient Near Eastern mythology.”

There is no evidence that Martello had any direct influence in the creation of the Minoan Brotherhood, but his early work as both a public Witch and gay rights activist undoubtedly contributed to the tradition’s framework.

In Bull of Heaven: The Mythic Life of Eddie Buczynski and the Rise of the New York Pagan, author and Minoan Brotherhood member Michael Lloyd describes the process by which the tradition came together.

“The inspiration provided by Leo Martello to Buczynski lay in his firm belief that gay men needed to be liberated from the shackles and expectations of society,” Lloyd explained. “Eddie took this message to heart when he created the Minoan Brotherhood in 1976-77.”

With Buczynski, Martello contributed to the formation of Welsh Traditionalist Witchcraft, and was subsequently initiated into that tradition. He was also an initiate of Gardnerian Wicca.

It was the Old Religion, however – known in Italian as La Vecchia – that defined Martello’s identity as a Pagan and a magical practitioner. In his best-known work, Witchcraft: The Old Religion, he explored what he believed were the origins of a Pagan faith that once thrived in Sicily. A rich tapestry of mythology, folklore and history, La Vecchia venerated gods and goddesses and understood the divinity inherent in nature. The Sicily Martello writes about is a place of ancient temples and sacred tombs; it was “called Trinacria and was literally the center of the civilized world.” According to Martello, the magic of that ancient land survived centuries of conquest and even slipped unnoticed through the steely edicts of the Roman Catholic Church. That very magic, he claimed, ran through his own blood.

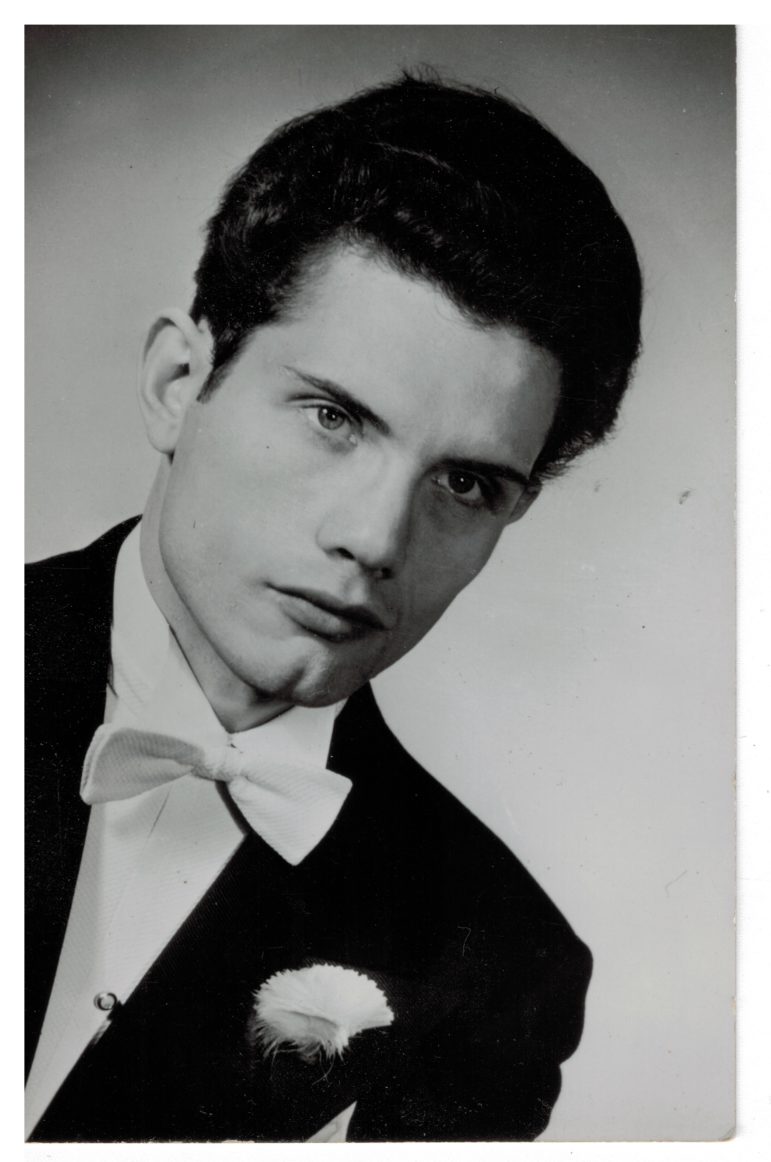

Leo Martello at 26 years of age, in white tie [courtesy L. Bruno]

Born in Dudley, Massachusetts in 1931, Martello was raised in a traditional Roman Catholic household. His father was an Italian immigrant. Little is known about Martello’s mother, other than that she left the family early on.

Following his parents’ divorce, Martello was sent to a Catholic boarding school in Worcester. He often described those years as the bleakest period of his life. By his own accounts, he was drawn to the esoteric before he hit puberty. In his teenage years, he had numerous psychic experiences, which led him to study palmistry and the tarot.

It was around this time that Martello’s father revealed to him two family secrets.

The first: Martello’s paternal grandmother was reputed to be a powerful maga – a female Witch – in her native Sicily who practiced folk magic and even cursed a Mafioso to his death after being threatened by him.

The second: Martello had several cousins in New York who were eager to meet him. Both revelations set the course for his spiritual awakening. As the story goes, Martello moved there and met his cousins, who were practicing Witches. They initiated him into their familial tradition and Martello immediately embraced what he had innately known himself to be: a mago, or male Witch.

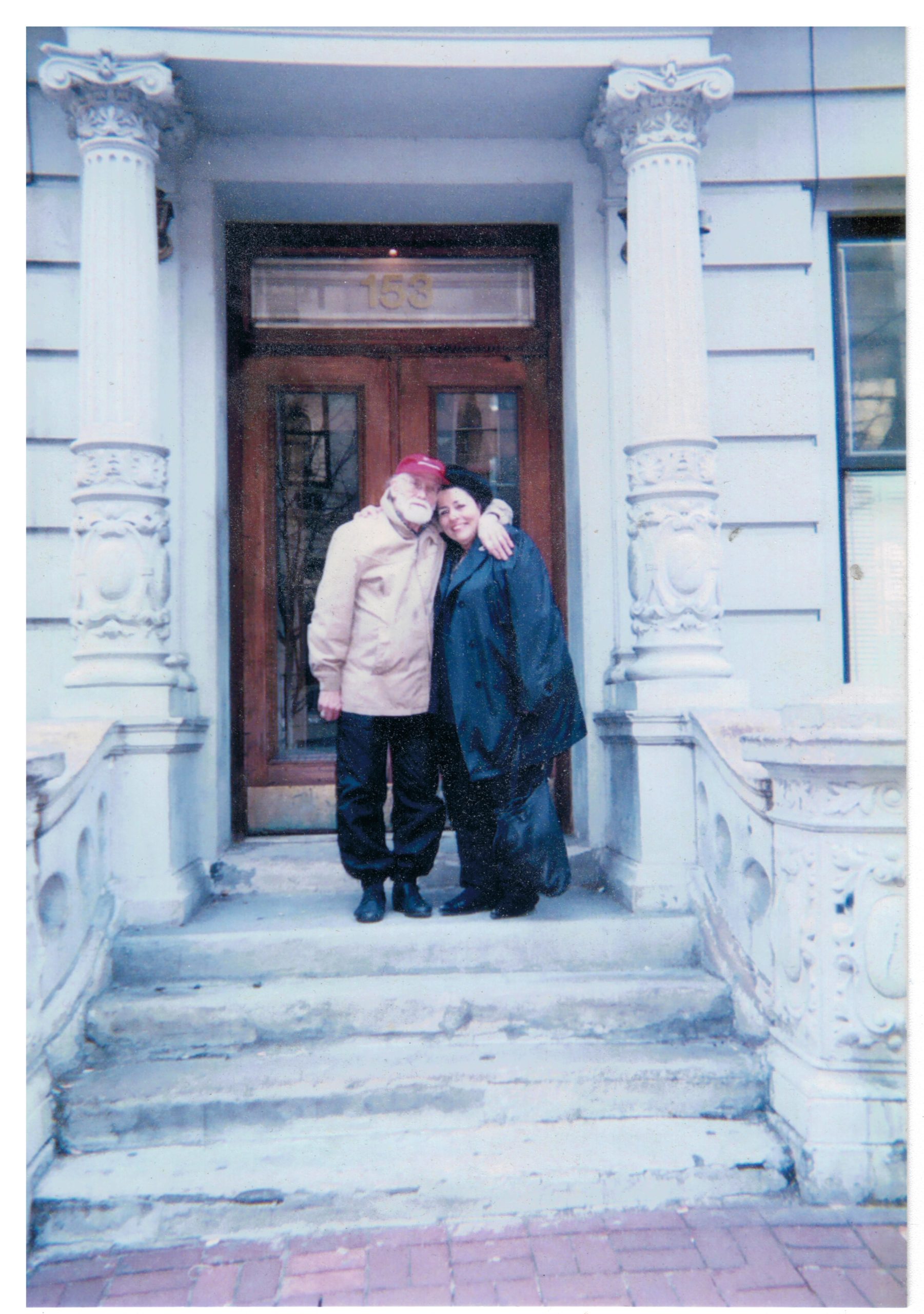

“Leo was of the highest moral character,” said Lori Bruno, Martello’s closest confidante and the executor of his estate. “He got his inspiration from his roots, his magic, and from the light that shined above him. He trusted that light more than he trusted people.”

Bruno, a hereditary high priestess and elder of the Sicilian Strega line of the Craft, formed an instant kinship with Martello when they met in New York City in the 1970s. They were, according to Bruno, best friends who shared a deep reverence for the Old Religion.

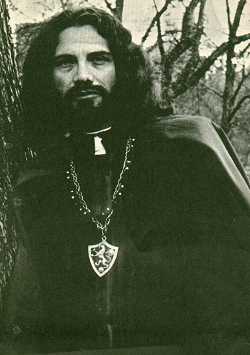

Leo Martello – Image credit: Astro-Gnostic Enterprises [courtesy, The Buckland Museum of Witchcraft & Magic]

They were also linked by the same magical heritage – Bruno’s lineage, like Martello’s, was rooted in Enna, Sicily, and she had also undergone her own family’s secret initiation into La Vecchia. That initiation included a sacred “last meal” followed by a burial, the details of which are kept private by practitioners.

“We don’t divulge certain things,” Bruno explained. “But the ‘burial’ we undergo is an ending of this life upon the earth, and then you reemerge into the life of light. There’s no more fear. The burial buries all of the fears you’ve ever encountered, and when you come out into the light, you know you will be strong.”

While strength was certainly a cornerstone of Martello’s personality, he has been described by many of his contemporaries as aggressive, caustic, and downright abrasive. That sharp edge, Bruno said, was matched by a compassion that knew no bounds.

“Leo cared for everyone,” she explained. “He didn’t like cowards. He despised people who hurt animals. He fought hard for the rights of the gay community and for Witches. He believed he could help people by using the energy that was within him from the gods, that he could tap into that force and create goodness for people.”

Martello authored several books about Witchcraft, the tarot, and other occult subjects, but rarely divulged aspects of his own magical practice. Much of that had to do with the oath of secrecy that accompanied his initiation. In Witchcraft: The Old Religion, he mentions that code of silence as it pertains to the ancient goddess of the Sikels: “Her secret name, which has been preserved for centuries, is known only to those who have been initiated into her worship.”

Bruno verified this claim. She also noted, as Martello did, that much of the Old Religion practiced in Italy survived because le streghe – the Witches – hid in plain sight of their oppressors, outwardly adopting Roman Catholic rituals while continuing their worship of the old deities behind closed doors. Only after receiving permission from his cousins did Martello begin writing about his faith. The majority of his published work, however, is decidedly impersonal. So what is the magic at the heart of La Vecchia?

Bruno gives us a clue. “As Leo would say: you are the candle, you are the sword, you are the pentacle, you are the chalice, you are the wand,” she explained. “Every part of you is that magical instrument. You are that magical instrument. Leo believed everyone was special, and that everyone had the ability to remember their own unique power. Love is the most potent magic.”

Those interested in glimpsing more of what comprised Martello’s life as a practitioner can do so at The Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick in Cleveland, Ohio. It is home to one of Martello’s altars. The Museum’s director, Steven Intermill, noted the significance of having the altar among its extensive collection of occult artifacts.

“Leo’s legacy is very important to us,” Intermill said. “I feel personally attached to him because the first book I ever read on Witchcraft was Witchcraft: The Old Religion when I was a teenager. Being able to tell a bit about Leo’s story to our guests is a lot of fun, and I know that he really resonates with many of our guests who are members of the LGBTQIA+ community.”

Indeed, the freedoms and practices enjoyed by new generations of Witches – including those from the LGBTQIA+ community – are the result of the groundwork done by Martello and many of his contemporaries. From the acceptance of Paganism as an official religion by the American government to the vocal protest movement among Witches during the Trump administration, the confident voices of magical practitioners owe a debt to Martello’s first battles.

He also paved the way for the popularity of the Stregheria tradition — best known through Charles Godfrey Leland’s Aradia: the Gospel of the Witches and the works of the late Raven Grimassi – by introducing its forefathers to readers in Witchcraft: The Old Religion, published first in 1973. And although he is not a household name in the Pagan world, traces of his oeuvre can even be found online by seekers of magical texts and ephemera. An unpublished manuscript of Martello’s was recently for sale on eBay for $2,000, and early copies of his books appear on sites ranging from Amazon to antiquarian booksellers.

When Leo Louis Martello died in on June 29, 2000, he left behind a legacy of magic, activism, and pride – most especially in his identity as a gay man. This pioneering spirit gives succor to those today seeking justice, those who value the intersection between tradition and innovation, and those struggling to be true to themselves in a world that is not always welcoming.

He did it with sharp elbows and an uncompromising outlook, noting in his best-known battle cry that: “The weak find a way out. The strong find a way.”

In this, he instructed his contemporaries and coming generations to be fearless, to embody the change they want to see in the world, and to move ever forward.

*Sikels are believed to have been an Italic people who occupied a region of what is today is known as Sicily; they reportedly inhabited this land before the Greeks and their influence.

Today’s article is by Antonio Pagliarulo. He has been a member of the Pagan community since his teens. The son of Italian immigrants, he was schooled in the ways of Italian folk magic and Stregheria and is a dedicated priest of the Old Religion. While a college student, he authored Rocking the Goddess: Campus Wicca for the Student Practitioner and American Witch: Magick for the Modern Seeker (Kensington Books) under the penname Anthony Paige. He is also the author of five young adult novels published by Delacorte Press/Random House. His reporting on spirituality and the occult has appeared in the Washington Post and Religion News Service. A full time writer and volunteer EMT, Antonio lives in Manhattan with his husband and is currently working on his first novel for adults, as well as a new volume of witchy nonfiction.

Today’s article is by Antonio Pagliarulo. He has been a member of the Pagan community since his teens. The son of Italian immigrants, he was schooled in the ways of Italian folk magic and Stregheria and is a dedicated priest of the Old Religion. While a college student, he authored Rocking the Goddess: Campus Wicca for the Student Practitioner and American Witch: Magick for the Modern Seeker (Kensington Books) under the penname Anthony Paige. He is also the author of five young adult novels published by Delacorte Press/Random House. His reporting on spirituality and the occult has appeared in the Washington Post and Religion News Service. A full time writer and volunteer EMT, Antonio lives in Manhattan with his husband and is currently working on his first novel for adults, as well as a new volume of witchy nonfiction.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.