Stefano Ciotti and Manny Moreno contributed to his article

LA PAZ, Bolivia – In Andean spirituality, Pachamama is the revered earth and fertility goddess, honored especially among the Quechua and Aymara peoples of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Argentina. Her name originates from the Quechua words pacha (meaning “world,” “earth,” “time,” or “cosmos”) and mama (meaning “mother”), often translated as “Mother Earth” but probably more accurately as “Mother of Time and Space.”

She embodies the life-giving force of the world, governing fertility, agriculture, and the well-being of humans and animals. Mountains, sacred landscapes, and the cycles of planting and harvest are closely associated with her, reflecting a worldview that sees nature and humanity as deeply interconnected.

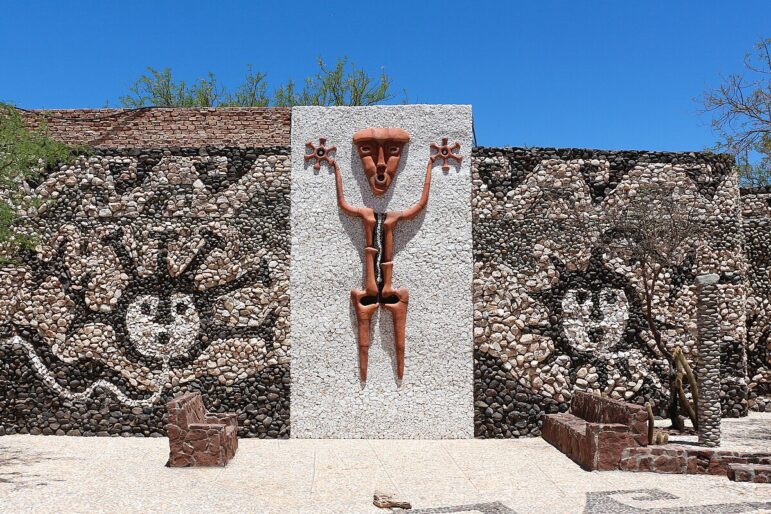

Pachamama Museum, Amaicha del Valle, Argentina [Photo Credit: Bernard Gagnon CCA-SA 4.0

People honor Pachamama through offerings called despachos—ritual gifts of food, coca leaves, chicha (corn beer), and sweets—often buried or burned to “feed” her. August 1 and the days following are especially significant, marking Pachamama Raymi, a major festival ensuring prosperity and protection for the year ahead. In everyday life, it is common to pour the first sip of a drink onto the ground in a ch’alla as a small act of reverence.

After colonization, devotion to Pachamama often merged with Catholic veneration of the Virgin Mary, a syncretism still present in rural rituals. During the October 2019 Amazon Synod in Rome, two unidentified men stole five Pachamama statues from a church and threw them into the Tiber River, sparking global outrage and praise from different Catholic factions. The Vatican, Indigenous advocates, and Pagan groups condemned the act as religious intolerance and violence, while ultra-conservative Catholics defended it as the destruction of “pagan idols.”

Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamayhua, Juan de (1613). Relación de las antigüedades deste Reyno del Piru. (Secund.:) Marcos Jimenez de la Espada (ed., 1879). Tres relaciones de antiguedades peruanas. – Madrid, Imprenta y fundicion de M.Tello.

In November 2019, Bolivian opposition leader Luis Fernando Camacho declared that “Pachamama will never return to the palace” after President Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first Indigenous head of state, resigned amid disputed elections and military pressure. Camacho, invoking Christian rhetoric, vowed to purge Indigenous spiritual traditions from government and “return God” to the presidential palace, sparking concerns over anti-Indigenous sentiment. His supporters burned the Wiphala flag, a symbol of Andean peoples, while Morales condemned the use of religion to discriminate against Indigenous communities. The political upheaval exposed divisions within Bolivia’s Aymara population and intensified tensions between secular governance, Indigenous identity, and religious politics.

The threats didn’t work.

Pachamama remains a powerful cultural symbol in environmental activism and Indigenous rights movements. Last week was Pachamama’s feast day.

As the Associated Press reports from La Cumbre, Bolivia, devotion to Pachamama remains deeply rooted in Bolivian culture. Neyza Hurtado, who was struck by lightning at age three, sat beside a mountain bonfire, proudly displaying the scar she calls the source of her wisdom. “I am the lightning,” she told AP. “When it hit me, I became wise and a seer. That’s what we masters are.”

Like every other August, hundreds of Bolivians hire Andean spiritual guides like Hurtado to perform rituals for Pachamama, or Mother Earth, whom the Aymara believe awakens hungry and thirsty after the dry season. “We come here every August to follow in the footsteps of our elders,” said devotee Santos Monasterios. “We ask for good health and work.”

Wiphala Flag [public domain

The offerings, called mesitas (“little tables”), are wooden platforms adorned with sweets, grains, coca leaves, and symbolic objects for health, protection, and prosperity. In some cases, llama or piglet fetuses are included. Once prepared, the mesita is set aflame, and participants pour wine or beer over it “to quench Pachamama’s thirst.” Monasterios explained, “When you make this ritual, you feel relieved. I believe in this, so I will keep sharing a drink with Pachamama.” After burning for hours, the ashes are buried, returning the gift to the Earth.

Carla Chumacero, who requested four mesitas for her family, told AP, “Mother Earth demands this from us, so we provide… Many people go through a lot such as accidents, trouble within families, and that’s when we realize we need to present her with something, because she has given us so much and she can take it back.”

Others, like miner María Ceballos, embrace the practice through community influence. “We make offerings because our work is risky,” she said. “We use heavy machinery and travel often, so we entrust ourselves to Pachamama.”

Bolivian anthropologist Milton Eyzaguirre told AP that the tradition dates back as far as 6,000 B.C., shaped by the Southern Hemisphere’s dry winter season from June to September. August is believed to be the month when Pachamama sleeps, and rituals are meant to strengthen her before planting in October and November. “These dates are key because it’s when the relationship between humans and Pachamama is reactivated,” Eyzaguirre said. Unlike other worldviews that treat land as a consumable resource, “here there’s an equilibrium: You have to treat Pachamama because she will provide for you.”

The August observances also honor the apus, mountains regarded as protective spirits for the Aymara and Quechua. “Under the Andean perspective, all elements of nature have a soul,” Eyzaguirre explained. “We call that Ajayu, which means they have a spiritual component.” For many, wind, fire, and water are spirits, and the apus are seen as ancestors, which is why Pachamama rituals are often held in highland locations like La Cumbre.

Veteran spiritual guide Rosendo Choque, a yatiri for 40 years, said such work requires both special skills and Pachamama’s permission. “I acquired my knowledge little by little, but I now have the permission to do this job and coca leaves speak to me,” he told AP. Hurtado, whose knowledge was passed down from her grandmother, says her relationship with Pachamama brings her the greatest joy. “We respect her because she is Mother Earth,” she said. “We live in her.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.