My Oma didn’t really use the front door of her little yellow brick house in Milwaukee. Most coming and going was done through the side door, which stepped directly into the kitchen. Inside the kitchen, hanging on the little bit of wall between the door and the table, hung the calendar from her church.

When I was little, the church she and my Wisconsin relatives attended was still full of German immigrants who came to the United States after the war. To their dying days, “the war” always and only meant the Second World War, the conflict in which they were driven from their village by Marshal Tito’s communist Partisans and put into extermination camps.

The calendar fascinated me back then. It was printed on a strangely textured and crinkly paper, and every day had something printed in its little box below the number. The days that weren’t Catholic holidays major and minor each had the name of a saint printed in a tiny font. So many saints!

In the celebrations of their traditional, old world religion, your birthday mattered much less than your saint’s day. The important date was the one associated with the saint you were named for, and everyone was named for a saint of some sort. My father was Johannes, and his father was Johannes. As its equivalent John is in English, Johannes is a solidly saintly Catholic name in German.

After my dad left the church, left religion, left Europe, and became a philosophy professor in Chicago, he and my philosopher mother named me Karl Erik – not only not thinking of any connection to saints, but accidentally giving me versions of the names that were more Scandinavian than German. I was raised in a humanist household, but taught that I needed to read the mythologies of the world (including the Christian ones) in order to understand great art, literature, and music.

It was always strange interacting with the fervently faithful world of my German relatives. One of my earliest memories is of visiting a great-aunt in Canada and sitting with my parents in her dimly lit front room. She told me she wanted to show me something, took my hand, and led me up the steep stairs of her old farmhouse. At the top of the stairs was a linen closet she had converted into a shrine. She held a statue of the crucified Jesus up to my face and told me to kiss it. In a Stephen King moment, I remember my parents rushing up the stairs to save me while I stood paralyzed by the weirdness of it all.

I never practiced a religion at all growing up, and I only came to the modern religion of Ásatrú as an adult after reading Padraic Colum’s retelling of the Norse myths and feeling this was the way for me. So it’s a bit odd that I now have a patron saint.

Baseball player with a notebook

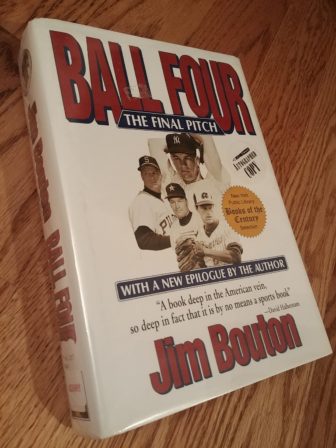

Last summer, I was looking for a good baseball book to read. After reading a bunch of “best of” lists, I settled on Ball Four by Jim Bouton. There was an autographed ex-library copy on eBay for cheap. And so it began.

Autographed, ex-library copy of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four: The Final Pitch [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

Bouton’s career as a pitcher started out conventionally enough. In 1958, the New York Yankees signed him out of Western Michigan University. He played in the team’s farm system until 1962, when he was called to spring training with the major leaguers. His breakout year was 1963, when he pitched in the All-Star Game, shut out the Minnesota Twins to win the American League pennant, and started game three of the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers. He won two World Series games against the St. Louis Cardinals in 1964 but suffered from a sore bicep in 1965 and had a miserable season. Even though he had a better year in 1966, his arm troubles led him to be sent down to the minors in 1967. He worked his way back to the Yankees in 1968, but was sold to the new Seattle Pilots and finished out the season down in the minors.

For most players, that would have been it. Rookie struggles would build to a performance peak, eventually followed by a decline and fade to black. But Bouton was definitely not like most players.

During the 1969 season with the Pilots, he surreptitiously took written notes and recorded a journal on tape to detail his experiences as he continued to bounce between major and minor league teams. He quietly worked with sportswriter Leonard Shecter to turn his notes and tapes into what became Ball Four.

For most players, the result would have been yet another book about the glory and heroism of baseball, about clean living and the American way. Even the surprise ending to the season – that Bouton’s relentless grinding resulted in being traded to the pennant-chasing Houston Astros – could have been part of a generic sports redemption narrative. Again, Bouton was definitely not like most players.

From first page to last, Bouton breaks the cardinal rule of the baseball clubhouse: “What you see here, what you hear here, what happens here, stays here.” Rather than spout inspirational platitudes and insist that faith in God and dedication to clean living leads to success in sports and in life, he presents an unvarnished portrait of the daily lives of professional baseball players. He tells of widespread use of “greenies” (amphetamine pills), of married players regularly sleeping with “baseball Annies” (female groupies), and of drunken antics performed by supposedly virtuous superstars. This was enough to get him called to the commissioner’s office, effectively blacklisted from baseball, banned from old-timers’ days at Yankee Stadium, and passionately hated by a generation of professional baseball players.

And that could have been that, except for two things. First, Bouton’s writing is absolutely hilarious. Second, he resolutely and repeatedly challenges widespread American beliefs, prejudices, and hang-ups about politics, race, religion, sexuality, and war.

Maybe due to the fact that he told the stories into a tape recorder, but definitely due to his skills as a writer, Bouton manages to capture the vitality of the humor of the baseball life – one liners, practical jokes, hijinks, and non-sequiturs. This kept me up late every night until I finished the book, but it wasn’t what made me love Bouton. And I do love him.

The pitcher and the World Serpent

Throughout the book, Bouton details his regular stands against the status quo. He travels to Mexico City to formally protest the inclusion of apartheid South Africa in the Olympics, volunteers to work with underserved African-American youth, and challenges the casual racism of his teammates and the institutional racism of his bosses. He supports students protesting against American involvement in Vietnam, questions the public Christocentrism of professional sports, and promotes workers organizing and taking collective action against owners. On the major issues of his time, Bouton was decidedly to the left of the baseball world and had no qualms about damaging his career by standing up on a long list of issues that Americans were fiercely fighting over.

This is what really hit me in the heart. As a progressive practitioner of Ásatrú who is out-of-step with the majority of Heathens on political, social, and theological issues, I felt like Bouton was a kindred spirit. I’ve often written about what I see as the symbolism of Thor’s willingness to stand up to the World Serpent, despite his actions leading to his own destruction. I believe we must stand up to the monsters of our own time, even though it means a steady stream of trolling, slander, declarations of blasphemy, and threats of violence in return.

Not only did Bouton stand against the monsters and face the professional consequences after Ball Four’s 1970 publication, he continued to swing his hammer in the book’s 1971 sequel I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally and in the 1981, 1990, and 2000 updated editions of Ball Four that together swelled its length from 371 to well over 500 pages.

Autographed copy of Jim Bouton’s I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

There’s more to life than baseball and politics, and Bouton was resolute in his honesty about all of it. I’m fine with admitting publicly that I sobbed uncontrollably while reading of the death by car accident of his daughter Laurie in one of the later Ball Four updates and of his open discussion of not only the deep heartbreak of that day but of the many years of powerful grief that followed. This expansive and expanded book about baseball was never really just about baseball.

Bouton never stopped grinding. After being ushered out of baseball in 1970 and building new careers as an unsurprisingly unorthodox television sportscaster, actor, and 1972 Democratic National Convention delegate for George McGovern, he decided to go back to baseball in 1977. Unbelievably, he worked his way into the minors and fought his way up to starting pitcher for the Atlanta Braves in 1978. He then became a novelist and businessman and – among other ventures – created and marketed Big League Chew, shredded bubblegum in pouches mimicking the chewing tobacco then popular with baseball players.

Bouton’s final battle against the earth-girdling serpent began in 2001 when he began working to save Wahconah Park, a minor league baseball stadium built in 1919 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. As he had done over 30 years earlier, he kept a journal and turned his notes into a book. Foul Ball was published in 2003 and, like its predecessor, was about much more than baseball. The harder Bouton worked on the stadium project, the deeper he became embroiled in local, regional, and national politics. What began as a small-time crusade for an old local baseball park became an exposé of a shocking conspiracy between banks, business owners, government officials, and multinational corporate conglomerates to manipulate the stadium issue as part of a massive cash grab, consolidation of power, and cover-up of serious environmental pollution.

When his publisher turned out to have ties to the forces involved and reneged on issuing the book as it stood, Bouton created his own company to get the book out. As he had done with Ball Four, he later wrote a follow-up edition that updated the story and followed his resolute fight to its depressingly bitter end. Thor doesn’t always beat the World Serpent.

Holy cards and baseball relics

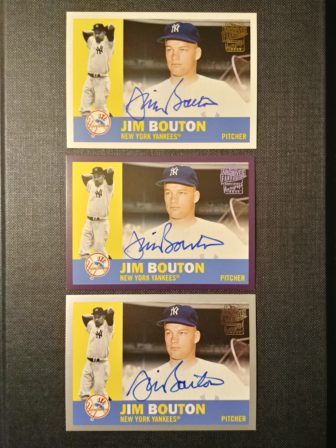

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a baseball fan in possession of an autographed item, must be in want of a collection. After reading Ball Four, I began haunting eBay in search of cheap autographed copies of Bouton’s other books. The more I read, the more I loved him and the more I felt that we were simpatico. After finding out we shared a birthday, I started to think of him – with tongue planted firmly in cheek – as my patron saint. But what’s a patron saint without holy cards?

I eventually found a surprisingly affordable autographed baseball card of Bouton on eBay. One led to another, and now I have binder pages full of them. If you’re diligent and follow an old retired player who isn’t considered a superstar by the masses, it’s amazing what you can get for under five dollars. I even picked up a picture postcard Bouton wrote to a young fan in 1963 saying he’s happy to be his pen pal. As with autographed books, part of the appeal of signed cards is knowing that the player actually held that same object at some point. Following Frazer’s “Law of Contact,” there’s a sort of magic to be felt when holding the signed card in your own hand.

Two Jim Bouton baseball cards: autographed 2018 Topps Archives and 2003 Upper Deck Sweet Spot relic [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

Relic cards are another step up the ladder of baseball religiosity. Most commonly, trading card companies purchase a jersey, some other article of clothing, or a bit of equipment from a player or collector, cut it up into tiny pieces, and insert those pieces into baseball cards. The fact that they are actually called relic cards is hilarious, since it connects them to the saintly relics – bits of bone or hair or clothing – so prized by the devout devotees of the medieval period. Equally hilarious is the fact that, as in the Middle Ages, there’s a long history of counterfeit relics passed off as authentic to obsessed collectors. Also following the religious model, the ones presenting the relics to the faithful are sometimes in on the fraud. Today, it’s trading card manufacturers doing the dirty deeds.

Some relics are better than others. My one Bouton relic card contains “an authentic piece of a jersey worn by Jim Bouton in an official Yankees® Major League Baseball® game.” So says the back of the card. I was happy to get this particular one, since it shows a nice pinstripe where all the others I’ve seen just have a snip of white cloth. I got it in a cheapie twofer with a relic card of old-time Yankees manager Casey Stengel, one of the subjects of Bouton’s 1973 “I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad.” The back of the card states, “You have received a Casey Stengel Game-Used Pants trading card.” I like to think it’s from the seat of his pants and that this relic once touched the butt of a Hall of Famer. Talk about contagious magic.

Saint Jim

To be crystal clear, I don’t actually pray to Jim Bouton. The coincidence of our birthdays, contiguity of our worldviews, and collectability of the autographs together put me in mind of my Oma and her devotion to the Catholic saints, with the accompanying material culture of sacred books, holy cards, and venerated relics.

Three different versions of autographed 2018 Topps Archives Jim Bouton baseball card [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

Bouton’s sort of saintliness was tainted by very human failings. He neglected to mention his own philandering while gleefully detailing the sexual adventures of his fellow players. He regularly participated in “beaver shooting,” the practice of horny baseball players climbing up on the roofs of their hotels to peep into women’s windows. He engaged in Loki-level workings in his relationship with Ted Turner, mogul owner of the Atlanta Braves, in order to push the magnate to advocate for his place on the team during his second run at a baseball career. Back in 1969, he was fiercely committed to racial and economic justice but casually engaged in the macho-man homophobic humor of the clubhouse.

The others I consider saints were definitely also sinners in the traditional sense. John Coltrane cheated on Naima, his first wife whom he immortalized in the beautiful ballad named in her honor. Malcolm X was a drug dealer and pimp in his early days. Jack Kerouac was truly awful to his wife and daughter. But all three of them, like Bouton, focused on challenging themselves to evolve as they spoke their truths loudly and damned the torpedoes of their society’s social enforcers. It’s that combination of continual growth and public action that attracts me to them.

I fully acknowledge that they said and did distasteful things at different levels on the sliding scale of wrong. I also insist that all of us do so, all the time. I don’t hold a monotheistic and monocular view of morality, and I don’t believe that anyone is wholly good or totally evil. The Norse gods and goddesses certainly are not, and the heroes of Germanic legend definitely are not. I believe the goal of the good life is to work to make sure your good deeds outnumber your bad ones in both number and magnitude. The web of wyrd is as complex as both ancient and modern life can be.

So saint is really the wrong word. I may have started using it after hearing Kerouac perform his poetic prayer to the recently deceased Charlie Parker in Mexico City Blues, comparing him to the Buddha and ending with a quasi-Catholic request:

Charley Parker, pray for me –

Pray for me and everybody

The fact that Kerouac addresses the creator of bebop as a saint tickled me when I first heard it, and it still gasses me as I read it now.

These days I should probably call Bouton, Kerouac, and the others ancestors, as we use that term ritually in Thor’s Oak Kindred to refer to those now gone who inspire us, those departed souls with whom we feel a kinship that can be stronger than that to an unknown and nameless progenitor. The fact that Bouton died on July 10 of this year now puts him in this ancestor category.

The horn beneath the oak

Seven years ago, on the fifteenth anniversary of his daughter’s death, Bouton had a stroke that affected his mind. Two years ago, he revealed to the public that he had cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a brain disease connected to dementia that led him to struggle with memory. What a terrifying prospect for those who write!

In the Old Norse poem Grímnismál (“Sayings of the Masked One”), Odin speaks of his ravens:

Huginn and Muninn

fly every day

over the great ground [the world].I dread for Huginn [Thought],

that he will not come back,

though I fear more for Muninn [Memory].

As we grow older, it’s terrifying enough to face the prospect of losing our ability to think clearly. But when we lose our memories, are we still ourselves? If we believe that we are our deeds, then beginning to lose the memory of those deeds means we begin to lose our sense of self.

Maybe we’ll get one more book from Bouton, and it will chronicle his experience of loss during his final years. I have a memory of reading that someone was working on the first comprehensive biography of Bouton, but I can’t find anything now. Maybe it was just a hopeful dream.

Autographed 2018 Topps Heritage Jim Bouton baseball card [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

I’ve been listening in the car to an audiobook of Bouton himself reading the final expanded edition of Ball Four. I play it on the way to teach, to rehearse, to perform, and to do everything else. It’s long, and I hope it goes on forever. I also hope I won’t be in a difficult driving situation when the powerful passage about the death of his daughter comes on. It’s amazingly endearing to hear Old Man Bouton crack up laughing when he reads the jokes preserved by his younger self. I can’t yet imagine what it will be like to hear him read his account of his greatest loss.

Since I first read Ball Four, I had been thinking about writing Bouton a letter and telling him how much his writing meant to me. As someone who moved from literature to music to religion and who teaches all three, I sympathize with the struggles, triumphs, and setbacks of Bouton’s polymath progression through multiple careers. As an outspoken opponent of bigotry, I appreciate the personal and public stances he took and the hate he received in return. As an old graybeard who was accepted into divinity school to work on my third graduate degree at age 41, I understand the challenges and satisfaction of his making it back to the big leagues at age 39.

As so often happens, life intervened, I never got around to writing a letter, and then he was gone. Such is the way of things. I’ll keep driving with his voice around me, and I’ll raise a horn to him the next time we gather beneath the oak tree and speak of those now gone who continue to inspire us.

The Wild Hunt always welcomes submissions for our weekend section. Please send queries or completed pieces to eric@wildhunt.org.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.