In August of 1619, a ship docked in Point Comfort, Virginia, holding cargo that changed history. The ship was the first to bring enslaved human beings from Africa to the American colonies. John Rolfe, the famous widower of Pocahontas and also the Virginia colony secretary, logged the cargo as “some 20. and odd Negroes.”

Weeks earlier, 350 Africans were forced onto the San Juan Battista, a Portuguese ship in what is now modern-day Angola. The San Juan Battista docked in Spanish-controlled Veracruz, Mexico, on August 30, 1619, with 147 Africans onboard. Sixty had been taken aboard two English pirate ships, the White Lion and the Treasurer. These events are attested by documents discovered in the Spanish national archives about 20 years ago.

The White Lion docked in Virginia and sold its cargo for food- the cargo John Rolfe documented. “Few ships, before or since, have unloaded a more momentous cargo,” wrote the professor and social historian Lerone Bennett in Before the Mayflower: The History of Black America.

Make no mistake about that landing: the American experiment – from the shape of its democracy to the foundations of its economy – was built on the enslavement of Africans. Democracy and slavery both began in a summer union 400 years ago in North America under the British flag.

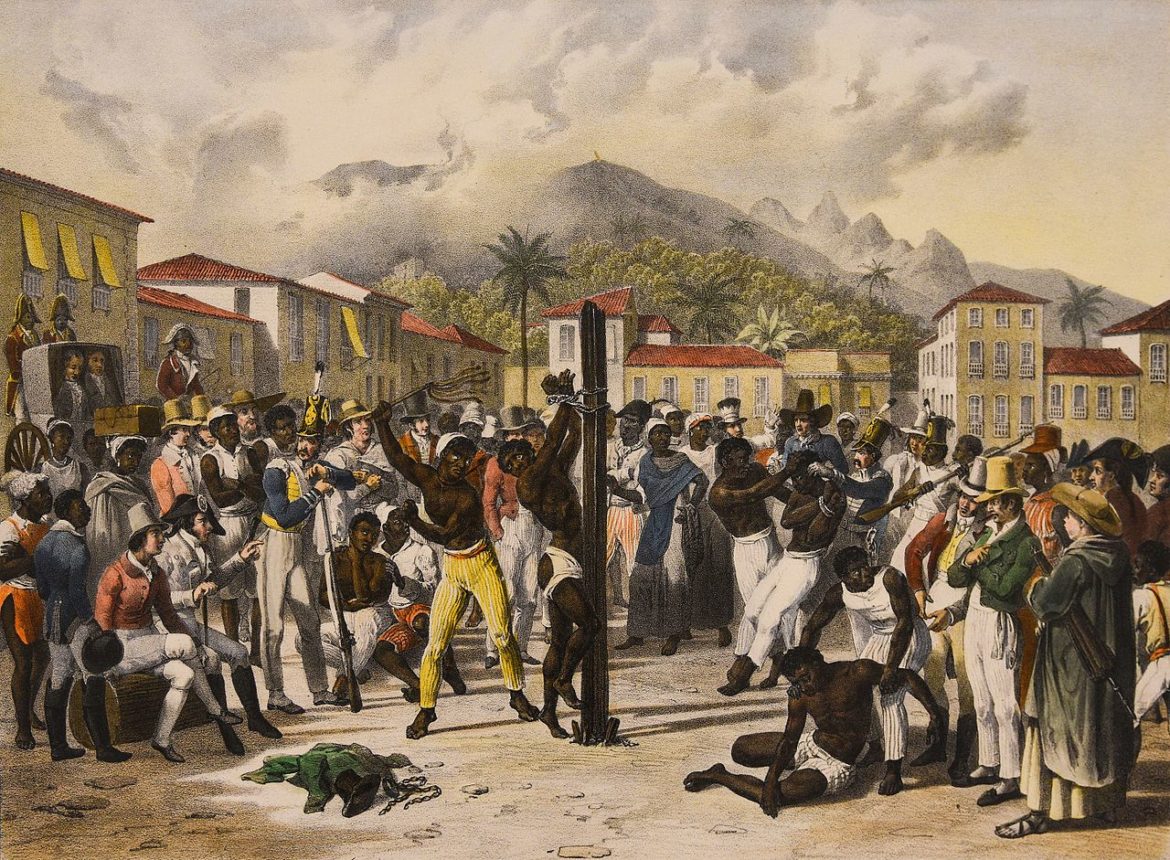

Slavery in Brazil by Jean-Baptiste Debret [Public Domain]

Until recently, this history has been silent, an injustice to our ancestors and their descendants. Look no further than the simple truth that many whites do not know that this week marks 400 years since the first slaves were brought to British America. A few weeks prior to the landing, the first elected body of representatives -foreshadowing the future nation- formed the General Assembly of the Virginia colony. To put the date into perspective, the Pilgrims arrived on Cape Cod on November 11, 1620, more than a year later.

Only two of the first 12 presidents never owned slaves; eight of those 12 owned slaves while in office. America was built by slaves, and its institutions coddled and protected slave-owners for centuries.

This is the history that we must look for because it is rarely taught. Slavery was not short-lived, marginal, confined to the South, or rarefied as many would have us believe. In response to those beliefs, we mustn’t mince words. Black history has been erased by white America.

This erasure is a moral convenience; it allows part of our nation to avoid the reality that slavery and its injuries have never ended. It continues to this day with overt inequalities in finance and healthcare, the disproportionate imprisonment and deaths of black men, and legislation that favors skin color. It exists as much in the narratives of science and medicine about “racial” disparities and pain sensitivity, and just as much in the cultural theft of African rhythms.

As professor Edward E. Baptist of Cornell University writes in The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, “The slavery economy of the U.S. South is deeply tied financially to the North, to Britain, to the point that we can say that people who were buying financial products in these other places were in effect owning slaves, and were extracting money from the labor of enslaved people.”

Modern America is deeply invested in the myth of racial differences. To address that investment and the realities of history, The New York Times brought to the fore this week a conversation that America, and every slave-trading nation, needed to have.

The 1619 Project is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.

It is a stunning exposure of American senility when it comes to race and slavery. It has received push-back. Former U.S. Representative and Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, who holds a Ph.D. in European History from Tulane, tweeted “The NY Times 1619 Project should make its slogan ‘All the Propaganda we want to brainwash you with.'”

Public flogging of a slave in 19th-century Brazil, by Johann Moritz Rugendas [Public Domain]

Here is another important factor in this history: racist views have frequently sought solace – and power – in religion.

As David Meager wrote in Cross Way, many Christians “assumed instead that Christendom was the new Israel and therefore that they could treat pagan peoples in the same way as Israel had done in the Old Testament. As God’s chosen people they believed that they had the right to enslave ‘inferior’ nations.”

Underpinning this view are passages from the Torah, such as Leviticus 25:44-6:

44 “‘Your male and female slaves are to come from the nations around you; from them you may buy slaves. 45 You may also buy some of the temporary residents living among you and members of their clans born in your country, and they will become your property. 46 You can bequeath them to your children as inherited property and can make them slaves for life, but you must not rule over your fellow Israelites ruthlessly.” (New International Version (NIV))

The passage suggests that Pagans – that is, those from other nations – may be purchased, sold and held indefinitely in servitude, even bequeathed to new owners. Only fellow Israelites were exempted from such ruthless rule.

Rick Hampson of USA Today succinctly links the process:

Seven thousand miles from Jamestown, on a rise overlooking the Atlantic just south of Angola’s capital city, Luanda, sits an old two-story white building. With a cross on its pediment and a sand-colored baptismal bowl inside, it might seem that its function, centuries ago, was sacred.

But this was a slave-trading hall. Tens of thousands of people were forcibly baptized, marched out the door and eventually put on ships headed west toward what Europeans called the Americas and Angolans called “the land of the dead.”

Forcible conversion offered the hope of redemption, while skin color offered evidence of inferiority. The traditional religions of West Africa provided another justification for oppression.

A few months ago, I was invited to deliver a lecture on race and religion in a seminar on modern societal challenges. I noted the usual issues that psychology as a discipline raises about prejudice and how motivated reasoning is employed by a group to preserve its power. I also noted in my presentation that I believe white supremacy is the moral challenge of this moment. There was a general agreement.

When I invited everyone to look into the eyes of their colleagues who are likely descendants of African slaves, they honored the reality of people near them.

When I began pointing out the continuing impact of slavery, specifically that nothing in modern American society is untainted by slavery, many in the room became noticeably uncomfortable, much like the 1619 Project is making many uncomfortable right now.

I think that discomfort is a good thing.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.