Sometimes, the Mead of Poetry works directly.

I suddenly have an entire tune in mixed meter with melody and chord changes pop into my head, and I sing it over and over during a four-hour drive until I can run into my office and write it out. It doesn’t feel at all like I composed it or created it. It feels like it simply appeared out of nowhere, poured into me by an external creative force.

Gunnlöð shares the Mead of Poetry with Óðinn (Carl Emil Doepler, 1905) [Public Domain]

Sometimes, the Mead of Poetry works indirectly.

An old rock ‘n’ roll song is stuck on repeat in my head, spinning unceasingly between my ears. Actually, it’s not even an entire song. It’s just a verse or a chorus or sometimes only a line or two. Someone else’s creative creation gets lodged in there, doing work on my mind that only I can hear.

Sometimes, there is a result.

That product of someone else’s creativity, that gift from another artist who themselves received the gift of inspiration, inspires me in turn. An ear-catching phrase or an evoked image turns and glitters in my inner light, and a new idea emerges.

So it has been, more than once, with the music of the Kinks.

The ambivalence of Ray Davies

Until late junior high, I mostly listened to pop music.

Sure, I knew a bunch of rock songs, but mostly because I heard them in rotation on the pop radio stations back in those long-ago days before streaming, before iPods, before the internet, when kids got their music by listening to whatever was played on the radio.

A major turning point was discovering rock ‘n’ roll radio DJ Dick Biondi on WJMK 104.3 FM Chicago, right around the time the station switched format to “oldies.” Back then, “oldies” meant 1950s and 1960s rock and pop mixed with Motown and a little bit of soul. It also meant music of the British Invasion like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Who.

And it also meant the Kinks.

The Kinks were different. Frontman Ray Davies really wasn’t like the precociously clever extroverted Liverpool lads in the Beatles or the in-your-face swaggering and strutting macho men Mick Jagger and Roger Daltrey.

Ray always seemed reluctant. Even when singing songs about girls and to girls, there was an inward turn to his persona and a fragility to his voice.

As the band developed through the late 1960s and into the 1970s, he embraced character portraits and an approach to rock music that was often closer to musical theater.

He also embraced ambivalence.

Sometimes, the ambivalence went straight over the head of a junior high kid like me until, one day, it smacked him between the eyes.

Well, I’m not the world’s most masculine man,

But I know what I am, and I’m glad I’m a man,

And so is Lola.

Of course, it seems so incredibly obvious now!

Many of Ray’s lyrics make the listener wonder what exactly Ray’s actual position or perspective is on the song’s subject. Is he creating a sympathetic portrait or sarcastically having a laugh? As he portrays characters, plays characters, and comments on characters, it can be unclear what is sincere and what is satire.

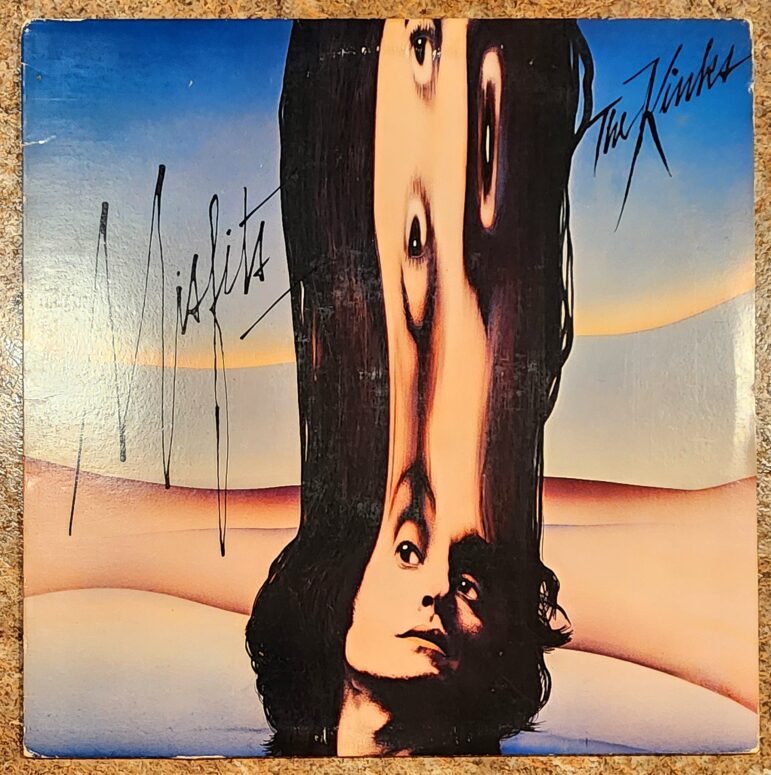

As a rock-obsessed high schooler, I always wondered about his songs “Juke Box Music” (from Sleepwalker, 1977) and “A Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy” (from Misfits, 1978).

I picked up both records from the 99 cent vinyl bin at 2nd Hand Tunes when I was preparing to see the Kinks play at the Holiday Star Music Theatre. I always liked to learn a band’s back catalog before going to see them. I still do.

Those two albums are still two of my favorites, nearly 40 years later.

“Hang on to a lot of the nice things”

“Juke Box Music” portrays a woman who loves music as much as I did and do.

She sings along with all the saddest songs,

And she believes the stories are real.

She lets the music dictate the way that she feels.

But the song’s narrator also states that “it’s only juke box music,” tells the woman “she’s in a fantasy,” and advises her that she “shouldn’t take it to heart.” The stories aren’t real, really.

Sleepwalker by the Kinks (original vinyl LP) [Photo by Karl E. H. Seigfried]

In those days, I was absolutely a member of what Lemmy Kilmister of Motörhead called “the electric church”:

Don’t you listen to a single word

Against rock ‘n’ roll

The new religion, the electric church

The only way to go

As a true believer, I definitely felt called out by Ray’s admonishments to not take it all so seriously.

“A Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy” portrays another dedicated follower of rock music, again with commentary from Ray-as-narrator.

There’s a guy on my block, he lives for rock

He plays records day and nightAnd when he feels down, he puts some rock ‘n’ roll on

And it makes him feel alrightAnd when he feels the world is closing in

He turns his stereo way up high

The narrator for this one states that this fan “just spends his life living in a rock ‘n’ roll fantasy” and concludes,

Don’t want to spend my life, living in a rock ‘n’ roll fantasy

Don’t want to spend my life, living on the edge of reality

Don’t want to waste my life, hiding away anymore

That ambivalence towards the power of rock music to both comfort and anesthetize does seem to reflect Ray’s own ambivalence towards his role as the front man of a big-time rock band in the psychedelic 60s and the arena-rock 70s.

It also put into words the mixed feelings I was having about sitting alone in front of my stereo for hours on end, figuring out bass parts to songs I would never play with a band on stage, while other teenagers were (I imagined) having adventures out in the world as if they were in a John Hughes movie.

That sense of being in two minds about something we love appears again in the song “The Village Green Preservation Society” (from The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, 1968).

In a 1968 interview on the BBC, Ray says,

I was looking for a title for the album about three months ago, when we had finished most of the tracks, and somebody said that one of the things the Kinks have been doing for the past three years has been preserving nice things from the past. So, I thought I’d write a song which said this.

Everybody’s trying to change the world. I’ve tried, and I’ll probably try again, but I don’t think you can change Britain that much, because we’re the way we are. So, I’m just going to try and hang on to a lot of the nice things.

The song itself is simultaneously earnest and tongue-in-cheek, with Ray both tapping into a heartfelt sense of nostalgia and pointing out its inherent silliness with his trademark music hall theater performer smile.

It’s the song’s refrain that has been stuck in my head for a while.

Preserving the old ways from being abused

Protecting the new ways for me and for you

What more can we do?

The song has been acting like a second-hand serving of the Mead of Poetry and giving me some ideas about the practice of Ásatrú and Heathenry, modern religions inspired by ancient Northern European polytheism.

“Preserving the old ways from being abused”

It was probably the song’s use of the term “old ways” that first got my imagination involved.

I often think of the new religious movement of Ásatrú as today’s descendant of the “old way” of the northern pagans before the conversions to Christianity. We know that – at least in Iceland – a parallel term was used in the medieval period, viz. the definition of siðr in the Cleasby and Vigfusson’s Icelandic-English Dictionary:

siðr (also in plur.) is the old and expressive word for religion, faith, as it appears in the life, laws, habits, and rites of a people; thus, inn Forni siðr, the ancient (heathen) faith; inn Nýi siðr, the new (Christian) faith; Kristinn siðr, the Christian religion; Heiðinn siðr, heathenism, etc.

Religion was seen as more than only ritual practice. It was a way of life.

Misfits by the Kinks (original vinyl LP) [Photo by Karl E. H. Seigfried]

As practitioners of Ásatrú today, part of what we do is preserve the old ways.

As an individual who began as a lone practitioner, I’ve long studied the old material that we still have from the Nordic countries, the continental lands, and the British Isles – not only the poems and myths preserved in written form, but also the lessons from archaeology, historiography, and modern scholarship.

I believe that anyone who’s really interested in the modern religion inevitably spends time studying its ancient roots in some form. By studying, we preserve the old ways within ourselves.

As goði (clergy) of Thor’s Oak Kindred in Chicago, I’ve worked to create open group celebrations that incorporate elements from Old Icelandic poems and prose, German folklore practices, records of northern European paganism, and the wider Indo-European religious world.

When we gather together for the various blóts (rites) of our ritual calendar, we preserve the old ways in a communal praxis that turns what we have learned from study back into living action once again.

As a teacher of Norse religion in secular settings (university courses, continuing education classes, public lectures, etc.), I approach the material as I would other world religions and guide students through an array of sources overlapping those that today’s practitioners spend so much time with.

Especially when teaching the Norse material in the context of a world religions course, I strive to show both the amazing parallels and the fundamental differences between this tradition and others both ancient and modern. By helping non-practitioners take this thing we love more seriously and learn about it more deeply, the old ways are preserved in the wider world.

The first line of Ray’s refrain is “preserving the old ways from being abused.” How do we, as Heathens of positive intent, prevent abuse of this material?

Maybe the most important way is by refusing to participate in the abuse ourselves.

If it turns out that the rune study group we joined is full of neo-Nazis and/or built around racialist völkisch (or neo-völkisch) materials, we shouldn’t say, “but there’s still a lot to learn here,” “Odin moves in mysterious ways,” or “even a broken sun-dial is right once a day.”

We should immediately disengage from those who abuse the old ways to forward their hateful worldviews and, even more importantly, let others know to stay far away from the group. There are plenty of other ways to learn about the old writing systems and their relationship to the old way.

If it turns out that a musician or band that we enjoy because of their use of Norse imagery and texts is tied to white nationalism and/or violent ideologies, we shouldn’t say, “but they totally rock,” “it’s just so cool that they do rituals onstage,” or “we can just ignore their personal politics and enjoy the music.”

We should be honest about the situation, avoid minimizing the problem, and decide what place that music has in our own lives. I understand that it’s complicated.

I teach, lecture, and write on the myth-inspired operas of Richard Wagner, but I openly discuss the fact that he was an extremely disgusting anti-Semite who built his ideology into his lyrics, and I fully understand those who reject his work totally. On the other hand, I threw out the Burzum album that a student gifted me, because screw that guy and his crappy use of this stuff for his gross ends.

If it turns out that a Heathen community we’re part of (online or in-person) welcomes, enables, excuses, and/or recruits racists, bigots, anti-Semites, Islamophobes, abusers, stalkers, neo-Nazis, and/or neo-völkisch folks, we shouldn’t say, “nobody’s perfect,” “we don’t talk about politics here,” or “as long as the group publicly says they support my own particular identity, everything’s copacetic.”

If a community welcomes us but also welcomes those who embrace hateful ideologies or commit gross deeds, we implicitly endorse their inclusion and the things they stand for. Instead of making excuses for staying, we should walk out and let others know the score.

But Ray isn’t only singing about the old ways.

“Protecting the new ways for me and for you”

I am not a reconstructionist. I have no desire to return to the world or worldview of the early medieval period or any other past period.

I’m a practitioner of the new religious movement of Ásatrú. My focus is on building a public theology that engages with the issues and challenges we face today, forwarding an in-person practice that is meaningful to participants (in whatever way they understand meaning for themselves), and engaging with the positive elements from the past that we feel connected to and inspired by.

A new religious movement is, by definition, new. And it’s in flux as we develop it.

“A Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy” by the Kinks (original vinyl single) [Photo by Karl E. H. Seigfried]

I believe that we must incorporate new ways that we value – new ways that are clearly not from the Viking Age, even if we can sometimes find loose analogues for them in the old texts, modern academic theories about the era, and so on.

These new ways are things like humanism, feminism, diversity, equity, inclusion, sustainability, democracy, social justice, nonviolent protest, interfaith cooperation, opposition to misinformation, and commitment to following the scientific method.

These are things that we should make central to our modern religion, because our religion is about living in the world, and our religion is about more than only what we do in the ritual moment.

Whether we call it a way or a worldview, it affects (or can affect) all aspects of our lived lives.

As a writer of public theology, I try to work through these issues in real time. I don’t insist that the answers I forward are the only true ones – or even the ones that I’ll still be arguing for in a year from now. It’s a process.

And we don’t have to agree.

My favorite line from “The Village Green Preservation Society” addresses this (sort of):

We are the Desperate Dan Appreciation Society

God save strawberry jam and all the different varieties

There are, quite obviously to anyone who has even a passing familiarity, many different varieties of Ásatrú and Heathenry. Nobody has to love them all, and they will continue to exist regardless of our opinion of them.

We’re under no obligation to obey anyone else’s theological theories. I can acknowledge that someone has a totally different view of Ásatrú that is deeply meaningful to them, but that doesn’t mean that I have to agree with it or support it.

It certainly doesn’t mean I’m some sort of heretic if I don’t follow the dictates of a Heathen group I’m not a member of and have no connection to. It’s your thing. Do you what you wanna do. Ditto for whatever you think of my ideas.

Acknowledging “all the different varieties” of jam doesn’t mean we have to individually enjoy the same ones.

I believe that a world-affirming religion should engage with the world we live in, but I acknowledge that some Heathens are seriously into a very ancient-era-focused faith. We don’t have to agree.

But I do think that we should focus on “protecting the new ways for me and for you,” with the caveat that the new ways deserving our protection are the positive ones, not the nasty ones. As long as an approach to this thing of our isn’t causing harm, your business is your business.

“What more can we do?”

We’re just people. We try to do our best, but we’re not perfect.

If we can each do some small part to preserve the positive from the old ways and protect the praiseful from the new ways, we’re helping move the pieces on the board forward.

Like Ray Davies, I sometimes feel ambivalent about the things to which I devote my time and my heart. What seems deeply meaningful and necessary one day can seem awkward and overwrought the next. Flux is key to this life we live.

I know one thing that never dies; the commitment to building a thoughtful theology and a positive practice.

What more can we do?

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.