This morning, the Supreme Court of the United States issued three opinions, each a vicious win for the Court’s conservative majority. In City of Grant’s Pass vs. Johnson, the court held that a person with no home and no bed in a shelter can be criminally prosecuted for sleeping outside. (Perhaps the poor should simply get on with dying, as one of the court’s ideological forbears once said, and decrease the surplus population.) And in Fischer vs. United States, the court held that a federal statute that clearly states it’s against the law to disrupt an official proceeding only applies to evidence tampering, not rioting – thus making it less likely that the January 6th rioters, much less Donald Trump, will face appropriate consequences for trying to overthrow the government.

Not that it matters much, I suppose, since the third case of the day went ahead and overthrew the government anyway.

United States Supreme Court Building By Carol M. Highsmith – Library of CongressCatalog: http://lccn.loc.gov/2011631106Image download: https://cdn.loc.gov/master/pnp/highsm/12900/12912a.tifOriginal url: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/highsm.12912, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91285025

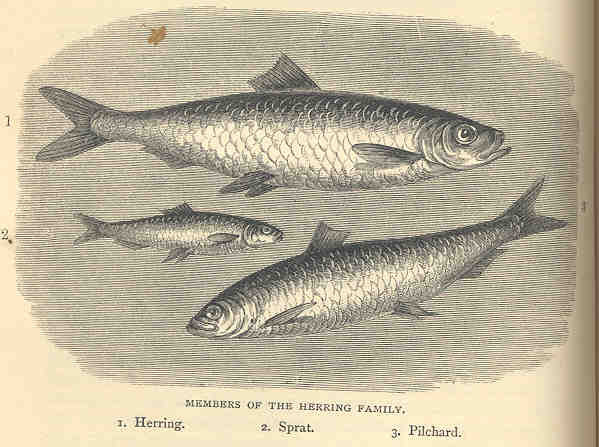

Am I exaggerating? A little, but not by as much as I wish. The third case, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, would appear on the facts to be utterly inconsequential. In brief, it concerns whether or not a company that catches herring must pay for the cost of a monitor from the government who ensures regulations are being followed – regulations such as “don’t fish the herring to the point of extinction.” The company sued, claiming that the relevant law – the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 – did not explicitly authorize the government to make the company pay for the monitors. They estimated the cost to be about $700 per day.

The lower courts, both at the circuit and appellate levels, all held that, although the law does not explicitly authorize this practice, it was a reasonable interpretation of the law by the government agency in charge of enforcing it, namely the National Marine Fisheries Service. The principle the courts used here is called “Chevron deference,” after the 1984 Supreme Court, Chevron USA Inc. vs. Natural Resources Defense Council. Chevron deference means that the courts will generally trust the decisions of government agencies in the areas apportioned to them by Congress – in this case, that the Fisheries Service should get the benefit of the doubt where the Magnuson-Stevens Act is ambiguous.

Today, in Loper Bright, the Court ruled on a 6-3 ideological line to overturn Chevron, using the occasion of a fishing expense to radically undermine the basic underpinnings of modern American governance.

In short, Loper Bright means that there is no room for reasonable inference by our regulatory bodies. You might think that the National Marine Fisheries Service, which was established to regulate our fishing industry, could expect to make decisions on how to carry out its mission. Not so fast, says John Roberts and the conservative supermajority. Now if there is any ambiguity in the law – and there will always necessarily be ambiguities in the law, because lawmakers are neither oracles nor saints – the Supreme Court says it has to be hashed out by federal judges, rather than an administrative system staffed by experts.

Why is this a problem? For three reasons, off the top of my head.

First: to be blunt, the typical judge has no idea what they are talking about when it comes to commercial fishing, or consumer protection, or affordable housing, or any of scores of other areas of modern life and commerce that are regulated by federal agencies. Thousands of decisions over the past 40 years have been premised on Chevron deference, allowing for agencies to keep pace with changes in American life. Now decisions about these areas will be made by whatever judge draws the case – or worse, plaintiffs will shop around for the most corporate-friendly judges. These judges have no guarantee of particular expertise, unlike the agencies tasked by Congress with overseeing certain fields.

Secondly: speaking of Congress, Loper Bright is premised on the idea that laws must be exact and unambiguous, that if Congress did not specifically authorize an action the agency by default cannot take it. But the U.S. Congress is in a seemingly-permanent state of gridlock; last year a record low number of bills were signed into law, just 27. Virtually nothing gets passed except for budget reconciliation bills, thanks to the Senate filibuster. Even when parties control the trifecta of the Senate, the House of Representatives, and the Presidency, they struggle to pass anything of substance. And now the Supreme Court says that Congress needs to explicitly authorize not just the creation of agencies, but every specific action those agencies might take to regulate their given areas? This is tantamount to saying there will be no further regulations at all.

And finally: our courts are overburdened as it is. There is a growing backlog of cases waiting to be heard and not enough resources for the judiciary to hear them in a fair and speedy manner. Overturning Chevron compounds the problem, as now every single disagreement over an interpretation of regulations must go before a judge, and potentially all the way to the Supreme Court. These lawsuits are likely to stress our legal system to a breaking point.

Members of the Herring Family, by James G. Bertram, 1873 [public domain]

Loper Bright is not an especially sexy Supreme Court case – it turns on procedural issues and judicial tests, and doesn’t have the immediate horror of something like criminalizing homelessness or depriving millions of Americans of the right to reproductive choice. But it is tremendously consequential, and is likely to have the net effect of giving an incredible amount of power to corporations and other wealthy interests who have complained for 40 years about “unelected bureaucrats” infringing on their rights to do whatever they want.

And one of the main agencies in the crosshairs will be the Environmental Protection Agency, which should be of concern to anyone who follows an Earth-based religion like most modern Pagan traditions. The EPA has already been hamstrung by the Roberts court over the past few years, which I wrote about at the conclusion to last year’s Supreme Court term – arguably Chevron was overturned for environmental issues in 2022 in West Virginia v. EPA. That case introduced the so-called “Major Questions Doctrine,” which states that questions of “vast economic and cultural significance” have to be clearly defined in statute. Loper Bright takes that one step further – now every question is liable to be a major question.

Climate science is exceptionally complicated, and explanations about climate change are often difficult to understand, leaving individuals with incomplete expertise on the subject to have exaggerated voices. Many individuals who do understand climate issues are working for polluters and have incentives to hide or distort the evidence. We need rational, effective translators of the science who can optimally communicate the evidence to people in other fields – like the law – so they can fully appreciate the documentary record without bias or spin.

There has been some reason for optimism about the climate – the Inflation Reduction Act has been much more successful than I predicted. We are building more renewable energy capacity more quickly than anyone anticipated. But climate change is still the most pressing issue for the world to come, and to fight it, we need agencies who can police the excesses of corporate interests.

We need experts on climate science to be able to stand up to polluters if we want to meaningfully slow our march towards catastrophe. For that matter, we need regulators with the power to make sure there are still herring in the Atlantic Ocean in 20 years.

All of that work to keep life on Earth viable is going to be a lot harder thanks to Loper Bright. In this case, as in so many others under Roberts, the Supreme Court has proven that their interests are the opposite of most modern Pagans.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.