Here in these United States, we’re again at a point where public protest is part of the national conversation.

Recently, student protestors have been receiving strong criticism from prominent figures on both sides of our political divide – the Democrat/Republican divide, that is, which is not necessarily the same thing as the left/right divide.

Some of today’s most controversial protests have very much to do with religion and religious difference, but there hasn’t been much public discourse about theologies of protest.

Painting of marching Vikings by John Charles Dollman (1851-1934) [Public Domain]

Two of the most important figures of 20th century movements for social change both grounded their actions in theology. Mohandas K. Gandhi based his concept of nonviolent resistance in Hinduism, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. adapted Gandhi’s work to a Christian framework.

I’ve long advocated for more to be done in the area of Ásatrú public theology. I agree with Sebastian Kim about the growing need for theology that engages with “public issues of contemporary society” and participates in “dialogue with different academic disciplines, such as politics, economics, cultural studies and religious studies, as well as with spirituality, globalization and society in general.”

How can today’s progressive practitioners of Ásatrú and Heathenry – of new religious movements that turn to historical Norse and Germanic paganism for inspiration while living in the modern world – build their own contemporary theology of protest?

A good place to start is by very briefly reviewing the work of Gandhi and King.

Soul-force

Gandhi wrote “The Gospel of Selfish Action” (1929) while in prison after being arrested by colonial British authorities for his work in the Indian independence movement.

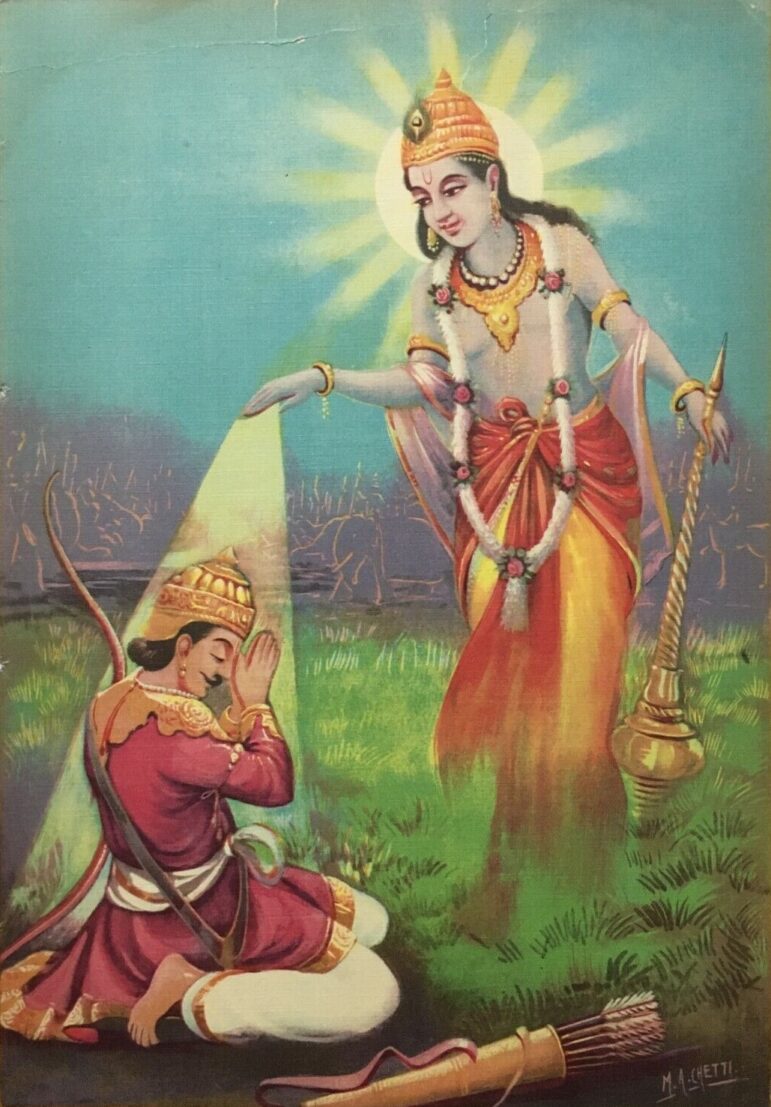

His commentary on the ancient Sanskrit Bhagavad Gītā (“Song of the Lord”) was written in response to a group of Hindu nationalist leaders who viewed the text’s hero Arjuna as a Hindu nationalist warrior and the god Krishna as his ethical advisor who counsels him to take up arms and fight against injustice.

The nationalists read Krishna’s monumental speech to Arjuna as a precursor of their own call for Indians to rise up against British rule. They also read the Bhagavad Gītā as a text that advocates and justifies violence.

Gandhi strongly disagreed.

Illustration of Arjuna and Krishna signed M.A. Chetti [Public Domain]

Calling the Bhagavad Gītā “the Book of Life” and his own “spiritual dictionary,” he writes that about his feeling

that it was not a historical work, but that, under the guise of physical warfare, it described the duel that perpetually went on in the hearts of mankind, and that physical warfare was brought in merely to make the description of the internal duel more alluring…

By ascribing to the chief actors superhuman or subhuman origins, the great Vyasa made short work the history of kings and their peoples. The persons therein described may be historical, but the author of the Mahabharata [the larger work containing the Bhagavad Gītā] has used them merely to drive home his religious theme.

The author of the Mahabharata has not established the necessity of physical warfare; on the contrary he has proved its futility. He has made the victors shed tears of sorrow and repentance, and has left them nothing but a legacy of miseries.

For Gandhi, this rejection of physical violence as a means of achieving social justice does not mean embracing passivity and inaction. As Fresno State Professor of Asian Religious Traditions Dr. Veena R. Howard explains,

Gandhi showed that the law of nonviolence was for all times. Especially in today’s social climate, it is important we realize the value of truth-force and soul-force.

He discovered nonviolence as a potent method of secure justice and peace and developed strategies and tactics, including civil disobedience, protests, marches, and non-cooperation. These methods have been wielded all over the world to defy structures of violence.

Gandhi’s nonviolence was active, not passive. The leaders of the civil rights movement and movements across the world have shown that nonviolent direct action is effective…

In today’s world, Gandhi’s teachings of resistance through nonviolent direct action and efforts to stand up for what is right, what is just, can help build just and harmonious communities. A realization of our wrongs, understanding our common humanity, and fighting for injustices would help heal the wounds of pain and violence inflicted on various people and communities.

One of the civil rights leaders who adopted Gandhi’s methods was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who adapted Gandhi’s theory and practice to fit within a Christian theological and African-American context.

Spirit and motivation

As early as the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, King looked to Gandhi as “the guiding light of our technique of non-violent social change.”

In 1959, King spent five weeks touring India, meeting and discussing with a wide range of people – from villagers and students to religious leaders, Gandhi’s family, and Gandhi’s closest colleagues (Gandhi himself had been assassinated in 1948).

Speaking on the radio shortly before leaving India, King said:

May I also say that since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense Mahatma [“great-souled’] Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation.

As summarized by the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, King’s concept of nonviolent resistance has six core principles:

- Evil can be resisted without resorting to violence

- Nonviolent resistance is not meant to humiliate the opponent, but to bring him to understanding

- Evil itself, not evildoers, should be opposed

- Nonviolent resisters must be willing to suffer without retaliating

- Nonviolent resisters must refuse to hate their opponents

- Nonviolent resisters must have “deep faith in the future” emanating from a conviction that “the universe is on the side of justice”

I can already hear the groans of the Heathens in the audience. Some of the groans are coming from me, myself. However, we don’t have to agree with everything King says in order to study and learn from his work.

The bits that seem most alien to those who venerate Thor, Odin, Freyja, and the other Ásatrú deities and spirits are also the bits that are most clearly and particularly grounded in Christian theology.

“As I delved deeper into the philosophy of Gandhi,” writes King in 1960, “my skepticism concerning the power of love gradually diminished, and I came to see for the first time that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.

“Christ furnished the spirit and motivation,” King continues, “while Gandhi furnished the method.”

How can those of us who follow the teachings of Odin and not the sermons of Christ make our own contribution to this dialogue of public theology?

“Call it malevolence”

Following Gandhi, we can begin by not reading our own lore literally.

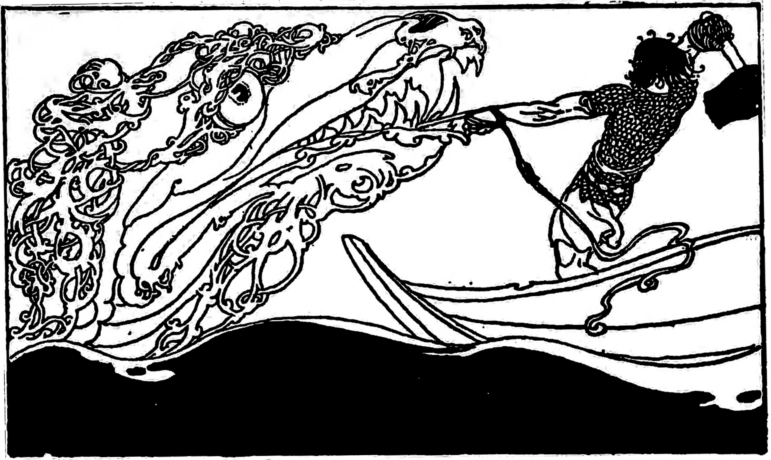

Instead of receiving Thor’s struggles with the World Serpent as instructions for using blunt weapons to exterminate water snakes, we can read them as a mythic/poetic reflection on both the moral imperative of standing up against evil and the deep personal consequences of doing so.

Thor eventually does vanquish the World Serpent at the final battle of Ragnarók (“doom of the powers”), but he stumbles back and dies himself immediately after winning the victory. As Gandhi writes of the parallel battle in the Indian Mahabharata, “the victors shed tears of sorrow and repentance.”

One of the things that the tale of Thor and his nemesis is about is the understanding that sacrifice is part of the true battle against real evil.

In this case, sacrifice does not have its usual Heathen meaning of “making a physical offering to the gods in the rite of reciprocal gifting known as blót” but instead fits the more general definition of “giving up something of oneself in service of an ideal.”

Gandhi and King both knew from hard experience that dedicated action in order to bring about meaningful social change and claim previously denied civil rights could come at great personal cost to those standing against oppressive forces. They were both willing to accept that cost. So is the thunder god of the Norse myths.

Physically assaulting those with whom you disagree is simple and simple-minded. It seems increasingly easy for even teenage boys to get guns and ammunition and shoot up people whose views – or very existence – they don’t like. There’s nothing strong or heroic about it, and it certainly isn’t changing our nation for the better.

Getting together with others of positive intent, joining in the community that Heathens speak of in such glowing terms, and openly standing against evil with full willingness to pay the price – whether getting brutalized by police or simply getting arrested and charged – that takes guts, or maybe the “soul-force” that Dr. Howard mentions.

“Soul-force” is actually associated with Thor, who is connected to ásmegin (“god power”) several times in the Norse myths. When most in need of strength to oppose the World Serpent, hostile giants, and malicious giantesses, he summons this particular form of spiritual power that seems much like the chi summoned by the kung fu fighter.

Illustration of the World Serpent and Thor by Willy Pogany (1920) [Public Domain]

“Christ furnished the spirit and motivation,” writes King. For Heathens, the inner spiritual power necessary to stand strong in the face of determined oppression and take the hard knocks that come with that stand can come from meditations on tales of Thor.

It can also come from the teachings of Odin.

Anyone with a basic knowledge of modern Heathenry in the United States is familiar with verse 127 of the Old Icelandic poem Hávamál (“Sayings of the High One”) and its injunction by the wisdom-sharing god Odin that (in Ursula Dronke’s 2011 translation)

where you know there’s malevolence,

call it malevolence–

and allow no peace to your enemies.

These lines can easily be read as a call to call out wrongs by those in power. More on what it means to “allow no peace to your enemies” below.

Odin is a deity who deals in strategy, advance planning, and finding clever ways to have enemies eliminate themselves. He advises his followers to be wise in all things and to be particularly so when dealing with those who would do them harm.

In verses 42 through 46 of Hávamál, Odin says to repay “lying with a lie,” to never be a friend of an enemy’s ally, and to hide your true thoughts from the untrustworthy. In direct contrast to the supposedly universal “golden rule” and the “turn the other cheek” message of Christ, Odin teaches that we have no responsibility to be love our enemies.

That particular Heathen teaching is a large part of what leads someone like me to be uncomfortable with some of King’s principles, but it does not mean that the embrace of violence is the answer.

To the contrary, Odin tells us to be smart in our dealings with those who would harm us, and getting violent during protests simply isn’t smart.

So what’s the smart Heathen thing to do?

Shield wall

If people of positive intent really do want to affect real change through nonviolent protest, we need to accept the basic reality that people in power disapprove of protesters.

They really disapprove.

It doesn’t matter what party they serve or what university they administer. It doesn’t matter what think tank they float in or how many conflict resolution training sessions their police department has had.

They all agree that protesters are inconvenient. They get in the way. They prevent the normal flow of business as usual. Maybe most importantly, they get the nation to notice things that the powerful would prefer to do without oversight or obstruction of any kind.

Sure, the folks in power say how much they respect the First Amendment and freedom of speech, but then they immediately go on to say things like “dissent must never lead to disorder” and “there’s the right to protest but not the right to cause chaos.”

At least, that’s what President Joe Biden had to say about the recent student protests.

When a follow-up question asked if the protests had led him to reconsider any policies, his answer was a simple “no.”

This doesn’t mean that nonviolent protest doesn’t have an effect. It simply means the protests haven’t yet gone far enough to overcome that condescending, paternalistic disapproval and to force the change.

To be truly effective, protest must be exactly what it has failed to be in recent years: widespread, disruptive, and sustained.

For nonviolent protest to have a real effect, it must be widespread. A college campus march here and there isn’t enough. It has to happen simultaneously all around the country, or it becomes just a series of isolated incidents that don’t build into a wider tidal wave of change.

Nonviolent protest must also be disruptive and lead to the exact situation that those like Biden fear most: “disorder” and “chaos,” which really means young people not quietly doing what they’re told, working as good little laborers, spending as compliant consumers, and unquestioningly voting for the approved candidate. Only when the daily norm is seriously disrupted will the powerful change course.

“Allow no peace to your enemies” says Odin. This doesn’t have to mean attack them physically. The disallowance of peace can be an active disruption of the tranquil continuance of everyday business by nonviolent protest.

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King warns of those who preach a false peace:

I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White citizens’ “Councilor” or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direst action” who paternistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.”

Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

It’s a bit awkward for our Democrat friends that the current president’s recent comments so neatly fit this scathing description, written seven years before Biden began a political career spanning six decades.

Most importantly and most difficultly, nonviolent protest must be sustained beyond the school vacation calendar and the convenience of the protesters themselves. It must continue through small victories and push on to codified systemic change, or things will simply snap back to the status quo.

One-day marches and even single summers of gatherings simply aren’t enough to change calcified systems for any meaningful length of time.

In 2023, just three years after the protests resulting from the death of George Floyd, more people were killed by law enforcement than in any other year over the past decade. Without large-scale protests, the killings will continue.

In 2024, four years after protests led to the tearing down of Confederate monuments and changing the name of public institutions named for Confederate characters, a Virginia county board is reversing the changes and reverting to school names honoring Confederate generals. In the absence of concerted pushback, the rollback will go on.

As practitioners of Ásatrú, we understand the importance of digging in for the long haul, whether it’s Odin working across the wide panorama of mythic time to minimize the toll taken at Ragnarök or Heathen service members and their supporters spending years working on gaining full recognition for their religious beliefs and practices by the U.S. Department of Defense.

It’s going to take dedicated work to clean out the corruption in our Supreme Court, to get Congress to stop posing for social media and instead focus on the serious work this nation needs, to fundamentally reshape law enforcement so that killing citizens isn’t something that so often only results in internal reviews and slaps on the wrist. There’s a lot of change that needs to happen, and we must be the change.

Are we willing to make the sacrifices needed to make real, lasting, serious, structural changes? Are we ready to literally link arms in a shield wall and refuse to move when militarized police in Judge Dredd gear demand that we disperse? Are we prepared to be imprisoned on trumped-up charges by Trump-appointed judges for daring to exercise our right to peaceful protest?

If that’s too scary, if we don’t really have the bravery that we boast about online, if we’d rather just pop open a beer and complain about things, the very least we can do is support the kids who are out there doing it.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.