GREAT YARMOUTH, Norfolk, England – Members of an art group named We Are Witch will be undertaking a pilgrimage on the weekend of the summer Solstice along the River Yare from Limpenhoe, near Norwich, to Great Yarmouth, Norfolk. The starting point is St Botolph’s church in Limpenhoe, as he was the patron saint of wayfarers. Participants Ruth Dillon and Eleanor Dale, who will be undertaking the walk in period dress, say that they aim to remember miscarriages of justice during the witch trials in Norfolk during their 10-mile walk. Ruth Dillon told the BBC that the pilgrimage offers

“…[a] unique opportunity to connect with people and place. I am interested in modern pilgrimage as an act of honouring and devotion. Walking was central to the lives of people in the 1600s and to the trials of the women persecuted as witches. In making and wearing period clothing, we hope to embody something of their stories and lives through cloth and stitch. Using clothing as a portal for connection allows us to share the project more widely with people we meet along the route.

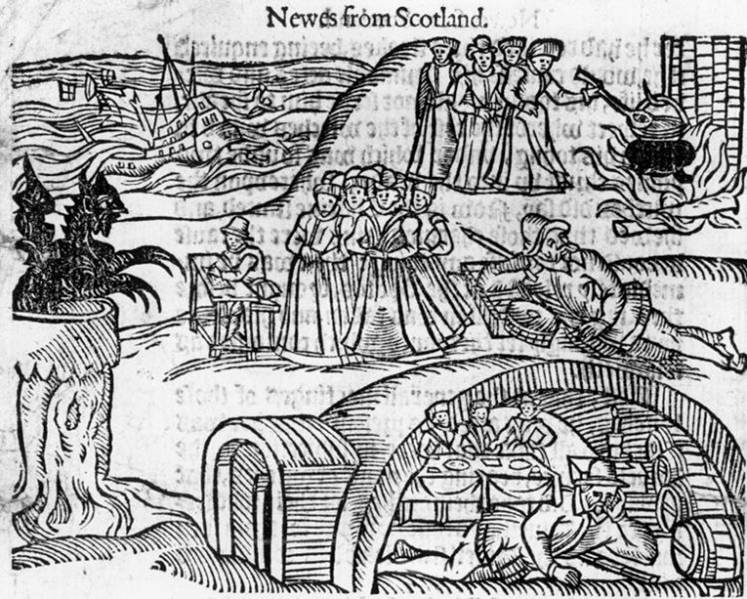

The North Berwick witches from a contemporary pamphlet, Newes From Scotland.

These women were killed at the height of the trials in East Anglia. It is hard to comprehend the fear that must have been present in communities where every woman was at risk. The project is called We Are Witch in recognition that if any one of us was born at a different time, we could have experienced the same fate; when women were singled out for being different, poor, single, disabled or for speaking their mind.”

Sound artist Charlotte Arculus will be joining the pilgrimage, telling the Great Yarmouth Mercury that

“When I heard this pilgrimage was happening, I immediately got in touch. I wanted to walk with it, to listen, to feel into time, and to sonically scry this journey. To remember, to mourn, to warn, to be with these women and hear and imagine their stories.”

East Anglia has a nefarious place in the history of the Witch Trials, and one of the principal players in the witch trials of England operated here: Matthew Hopkins (born c. 1620) known as the Witchfinder General. His title was not an official one, but one he adopted himself – yet it allowed him to organise the trials of around three hundred women in the 1640s and a hundred deaths.

Women being hanged for witchcraft, Newcastle, 1655. “A. Hangman, B. Bellman. C. Two sergeants. D. Witch-finder taking his money for his work.” [public domain

Hopkins was born in Suffolk and was the son of a Puritan clergyman. He is alleged to have been trained as a lawyer, but we have no direct evidence of this. With a professional associate, John Stearne, Hopkins set himself up as a witch-hunter. Hopkins claimed that this began after he overheard a conversation between some women in Manningtree about their concourse with the Devil, but his career as a witch-hunter seems to have begun with accusations made by Stearne. Twenty-three women were subsequently tried at Chelmsford by Justices of the Peace overseen by the Earl of Warwick.

Ronald Hutton has attributed some of Hopkins’s success to the Civil War itself and the collapse of the assize system, since under normal circumstances, these women would have been tried at the assizes and under its more formal rules, could have been acquitted. However, the Civil War left a power vacuum that Stearne and Hopkins took full advantage of. Both Stearne and Hopkins claimed to have been hired by Parliament, which does not seem to have been true, and with some female accomplices, they both made a considerable amount of money from witch-hunting. Parliament expressed considerable concern about their activities, and a report from the area to Parliament mentions ‘as if some busie men had made use of some ill Arts to extort such confession’.

Hopkins stated in his book The Discovery of Witches that the self-styled witch finders’ investigations were based on the Daemonologie of King James. Their methods remain familiar to most people today: ducking a witch to see if she floated, pricking her (it’s usually ‘her’) with a trick needle to see if she bleeds, and so on. There was some pushback. Hopkins was warned against ducking people without their permission (who would agree to this?) and was forced to give up the practice around 1645, having to rely on the ‘Devil’s mark’ instead. This is supposed to be a third nipple, but in Hopkins’ interpretation, it could simply be a birthmark or a mole instead, and unfortunately, a lot of people had these.

One of Hopkins’s principal opponents was a vicar: John Gaule of Great Staughton, who preached against witch-hunting. Then Hopkins and Stearne came to the attention of the justice system themselves, but they prudently retired before they came to court. Hopkins died in 1647, probably of tuberculosis, although there is a legend that he was subjected to his own swimming test. However, the terrible legacy of his actions and those of Stearne could not be undone and remain one of the nastiest episodes of English history in relation to accusations of witchcraft. 11 women were tried at the Great Yarmouth Tolhouse and 5 were convicted: Alice Clisswell, Bridgetta Howard, Maria Blackborne, Elizabeth Dudgeon and Elizabeth Bradwell were hanged. The Tolhouse will be open on Sunday, 22nd of June, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., as part of the pilgrimage.

The injustice of this, and other trials, is what the pilgrimage is hoping to commemorate, and the project also involves a needlecraft project culminating in the making of a quilt.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.