I came out of the closet in 1988 at the age of 17.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s, I didn’t know any queer people. I never saw them. Not knowingly, at any rate. There were no queer characters on television or in popular movies, and when there was a rare queer character in a movie, they were either the villain or a tragic figure. Always were they an object of scorn and/or pity.

The topic of homosexuality was never discussed, save perhaps for brief mentions on the news. At that time, it was legal (and common) for homosexuals to be denied security clearances or have their previously obtained ones revoked, as they were considered a “security risk.” I remember this being discussed multiple times on TV as well as on news radio programs. There was never any substantive reason given. Just a “security risk,” presumably in the form of blackmail, since engaging in same-sex acts was still considered morally repugnant, deserving of condemnation and scorn, as well as being illegal. Consenting adults could be thrown in jail for engaging in same-sex acts, and very few felt that was wrong.

Closeup of the handcuffed hands of a man patterned as the gay pride flag to denounce the criminalization of homosexuality in some countries. [DepositPhotos]

Though all this was depressing for a closeted queer boy to hear, it told me two things: 1. That homosexuality existed, and 2. That it was a bad thing to be.

This only became worse when the AIDS crisis began to be reported in the mainstream news. Now, homosexuals were perceived as the carriers of disease, and so the contempt and hatred grew. Closet doors got harder to open. An entire generation was wiped out. They simply disappeared. Lost were the gay elders. So much was lost.

I didn’t consciously realize I was gay until just prior to my coming out. I had long known that I was attracted to other boys, but my mind compartmentalized those feelings, so I never had to fully confront them. But my sexuality was something that others could plainly see. Going back as far as kindergarten, I was more comfortable hanging out with the girls on the monkey bars than playing sports with the boys, but my mother knew the truth of who I was when I came home sad from school one day.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

I told her about a boy in class who announced it was his last day at school since his family was moving to another state. My mother, never having heard me talk about this boy before, asked me if we were friends.

“No,” I replied. “I just like looking at his face.”

Out of the mouths of babes.

Through compartmentalization and denial, I struggled through my childhood. I was bullied relentlessly, and I learned to withdraw and hide in order to protect myself. Things only got worse for me in high school, where my tender heart and artistic personality made me a neon-colored target. It was a daily occurrence for me to be verbally attacked with hateful slurs. Words like “faggot,” “homo,” and even the more whimsical “fairy” were often leveled against me, usually by the other boys who were enacting the then societally accepted practice of ritual shaming.

Had I known of anyone else who was gay, it might have helped me not feel so isolated and alone. But I didn’t. It wasn’t until after I left high school, came out, and met my first boyfriend, that I would be exposed to any form of queer culture.

I, like so many of my fellow Gen X queer folk, did not have the “normal” adolescent experiences of dating in our formative years. While our straight friends were allowed to explore themselves with time-honored rites of passage like dating and attending school dances, we often retreated into obscurity or, in some cases, performed as society demanded, living a lie in order to make others feel more comfortable. This, perhaps, can account for what is often seen as protracted adolescence in older gay adults as we sometimes find ourselves indulging in those things that, at the time, were outside our safety zone.

This has all been bouncing around my brain as I recently decided to catch up with the rest of popular culture and finally break down and watch the Netflix hit Heartstopper.

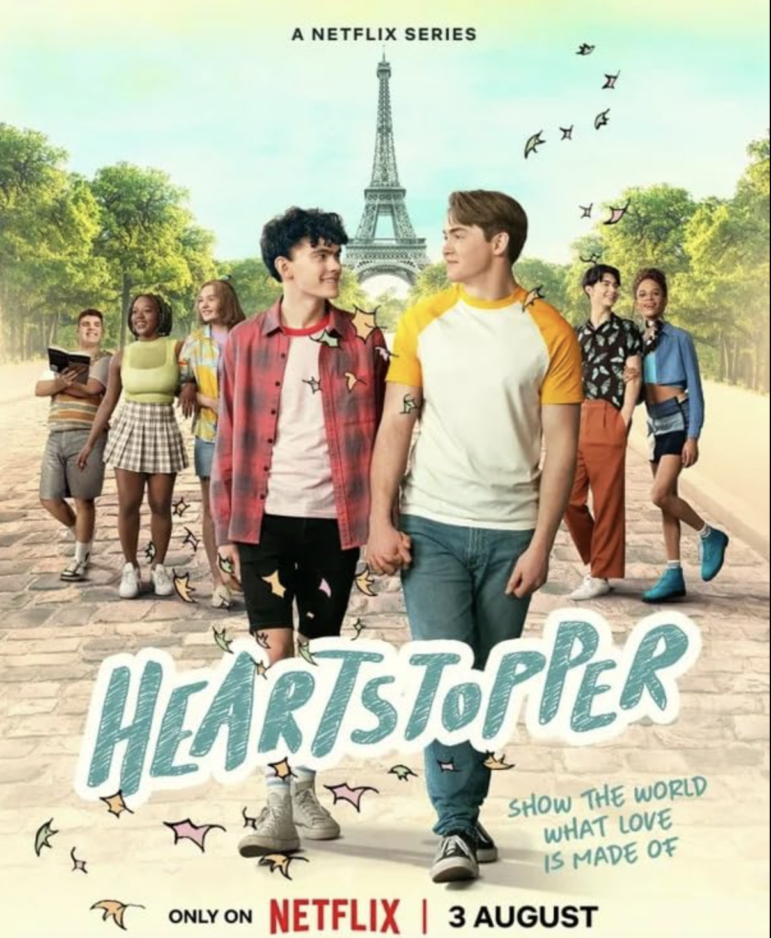

Promotional image of “Heartstopper” [Netflix]

For those of you who were, perhaps like me, living under a rock, let me break it down for you. Based on a webcomic by Alice Oseman, it is a queer coming-of-age story centering on (mainly) two high school students, Charlie and Nick. The story is just frankly adorable, offering some of the most wholesome queer characters and stories I have ever had the pleasure of experiencing. For Gen Z and Gen Alpha, this offers what I never had: positive representation and visibility.

As I watched the current two seasons of episodes, I often found myself driven to tears, not because of sadness, but because I felt it was so profoundly healing to see. Here, I saw myself placed in the context of a world that still had its challenges but was still far more accepting than the one I had grown up in. I saw myself in these boys, driven by their hearts but also fearful of what might befall them for daring to be vulnerable.

But unlike the queer stories of the past, here, their love was mostly celebrated, even as they thoughtfully navigated very serious issues like fear, consent, assault, self-harm, and mental illness. I saw myself in these stories, aspects of my life mirrored in both the triumphs and the pains experienced by these characters. I was reminded of my first kiss; how romantic and passionate it was, and how the very act of it was that of proud defiance. The feeling of discretely touching the hand of a lover, feeling the electric spark of desire and connection, even as we both maintained an outward composure so as not to illicit unwanted attention. And even the feelings of loss, and fear, and heartbreak. Common experiences for anyone but made far more potent for queer folk by placing the focus on queer identities front and center. “We’re here. We’re queer.” And we’re not going anywhere.

As I move further into my fifties, edging ever closer to that title of elderhood, I am left wondering how my life might have been different had I seen positive queer characters on TV and in movies while growing up. Would I have wasted so much time hiding? Would I have been more confident about my needs and my boundaries? I certainly would not have felt like the freak of nature I thought I was. But instead of being bitter for what I didn’t have, I am filled with a profound sense of hope for what the future may bring. The next generations will have some potent tools that I did not. And that’s true progress.

Heartstopper is available to stream on Netflix.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.