When I was a child my friends lived in the trees. There was an elaborate process to calling them down to play – a visit to each tree in turn, addressing the canopies and pulling on invisible bell-ropes, alerting them in a specific order so that each of them could clamber down and join the crowd. In about 30 minutes I would be followed by a panoply of colorful figures, each of them with their own opinions on what should come next. We would spend hours exploring the yard, racing to see who could swing highest or jump furthest, playing out involved stories of the tiny kingdom bounded by the fence and ruled by our collectively elected monarch – a position I accepted with solemnity.

It’s the sort of story that makes Pagans nod with a certain level of knowing humor when I tell it, drawing conclusions about who might live in the trees of a rural farmhouse and keep company with a lonely child. Those conclusions get a little more complicated when I tell them the names of my friends – Han Solo and Bastian Balthazar Bux, Robin Hood and Jake Berenson, a dozen other names that would have been familiar to any of my third-grade colleagues.

Still from the American drama film Sherlock Holmes (1922) with John Barrymore [Public domain]

“Oh, well-” one of my friends said, hearing the litany of Disney characters. “Maybe they let you call them that, but it must have been the local spirits playing with you.”

“I mean,” I said, thinking of complex sigils scrawled with the point of a stone on the concrete patio. “I summoned them. When I saw a story I liked, I would just – go out, and call the character, and ask if they wanted to be my friend.”

My friend frowned. We had talked about divination and channeling, talked about the foibles of our shared spiritual acquaintances. This was the first time they seemed to doubt me. “And someone answered,” they said, at last. “Spirits don’t always care what you call them.”

I felt my face heating up and grinned, diffusing the conversation as best as I knew how. “Yeah, I know,” I agreed. “I was a kid – might have just been talking to myself.”

There is a terrible missed-step feeling when I find the moment a friend can no longer believe me when I’m talking about my experiences. It’s shock at first, but it quickly dulls into shame: at being too strange, too credulous, too outlandish even among outlandish folk. It’s hard for me to believe anything when I hit that point, and often I find myself walking my own experiences back to check them for holes. Do I remember things the way I thought I did? Is there room for a different interpretation? Many things that are dear and vital parts of my practice have been curtailed by shame.

I remember the day that I, knowing myself too old for imaginary friends, walked from tree to tree, called each of them down, and exiled them from my lands. I considered it kinder than having them wait, arbor-bound, for another game that would never come, and I lived the rest of my time in that house with an empty yard and a feeling of loneliness that I couldn’t shake.

I’ve thought about that day often, especially as my spiritual life grew and developed into a vibrant community of friends – some of whom are as insubstantial as those who I played with as a child. I’ve turned my memories over, looking for some clue of who I might have been playing with- because interacting with the gods and the spirits of ancient cultures seemed much more reasonable than calling up the shades of Gondor.

This line of reason – that spirits and fictional characters were, in some vital way, completely separate things – lived in my head alongside a fascination with the ways we talk about fictional characters. Psychologists talk about parasocial relationships, in which readers bond with the characters of their favorite books. Authors describe characters ‘misbehaving’ or ‘showing up uninvited’ into their works. Fandom communities even create internally consistent, recognizable characters from whole cloth, sharing an understanding of who a particular person is and even what they look like without any shared text to reference.

These are all explainable phenomenon, examined by any number of articles and essays – but the conversations echoed with concepts I was running into in metaphysical circles. Pop culture Paganism still seemed fundamentally silly in some way, but I kept returning to it, trying to figure out why. If I could say that Loki had an opinion about how my most recent essay should go, and I could say that a character had an opinion about how my most recent chapter should go – why were those inherently different things?

If Dionysos could show up uninvited and distinctive in my life, and Darcy Lewis could become a defining characteristic of a fandom where she hardly existed in the main text, why did I only consider one of those a person?

I could not find a satisfactory answer, so I turned to the greatest mind I knew. I called Sherlock Holmes.

Statue of Sherlock Holmes at Meiringen, Switzerland. Created by British sculptor John Doubleday. Unveiled September 10, 1988 [Juhanson, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

My relationship with Holmes – parasocial or otherwise – may not be the oldest connection I have, but it is certainly one of the deepest. Growing up, my father had Baring-Gould’s two-volume Annotated Sherlock Holmes on the shelf, great green volumes that I would struggle to lift down safely and pour over. I sought him out in every form I could find him – from Gregory House to Basil of Baker Street – and as many versions of the stories as I could dig out of libraries or catch on PBS.

I knew Rathbone and loved Brett and for an only slightly regrettable three years I fawned on Cumberbatch. But it was the underlying character, the through-line that all of the various versions referenced, that I returned to again and again.

When a character is as old as Holmes, and has endured as many adaptations, there are very few central characteristics that remain in all of their versions. Holmes is always brilliant, certainly, and many versions of him are plagued by the difficulties of that brilliance in some form. He is accompanied by a Watson – often a doctor, sometimes an android, always the more normatively social one. He solves mysteries. Beyond that the details are hazy, but he is always recognizable as himself. Hound dog or mouse, judge or doctor, Holmes is unmistakable.

He’s also vital in a way that very few other characters are. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, famously, learned this much to his dismay. From the time Conan Doyle started to publish the stories, people began to write letters to Holmes, firmly believing he was real and in a position to write back. When Conan Doyle released the story that killed Holmes the entire nation mourned, with many papers running the news on the front page and others publishing it in the obituary section. Holmes has never been “merely” a character – from the beginning, he has been considered a person in and of himself, specific and very much alive.

If I could reach anyone, if there was anything to pop culture spirits at all, I was sure I could reach Sherlock Holmes. I even knew exactly how I would go about it. The formula was right there in the text – I would write a letter and address him exactly as one of his clients might. Then I’d borrow from my magical practice and do a reading to see if he had anything to say in return.

It all seemed like a very silly game, the sort of magical shenanigan that is as likely to result in gibberish and a fun story as anything else. My hope was to put the matter to rest and prove that, whether I could put a finger on it or not, there was a meaningful difference between fiction and spirituality. I wanted to know that any overlap between the two realms came from spirits meddling in the made up and fantastic for their own purposes. And, after all, Holmes would be the first to say that a matter should be examined in the light of reason. I would run an experiment, and put this behind me once and for all.

I was grinning when I sat down at the table. “To Mr. Sherlock Holmes, 221B Baker Street, London,” I said to the empty air. “Dear Sir-”

I composed a letter on the spot, calling up the tone of the correspondence in the stories, using my very best and most old-fashioned manners. Then I shuffled and turned over the first card.

I am not usually good at reading for myself. Turned inward, my intuition fails and I agonize over meanings, second guessing every insight until the tarot is just a pile of cardstock. I do not, as a general rule, get straightforward answers, and I certainly don’t get them in the clear, amused tones of an English gentleman.

My dear friend, the reading began, I have received your letter-

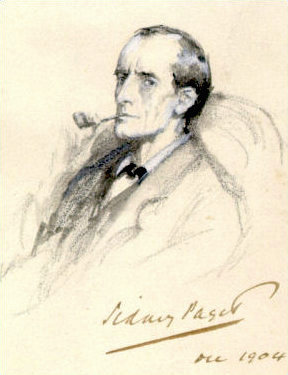

Sidney Paget, Portrait of Sherlock Holmes, 1904 [Public domain]cO

I am still struggling with what this means to me. It is not, given a bit of time and space to sit with the shock, a particularly worrying development. The world that I live in is already full of people, each of them worthy of respect and consideration in their own existences. If this suggests that it is bigger than I had considered, more full of life – well, isn’t that a lovely thing?

It’s only a suggestion – Holmes is unique, a character with history and weight that makes him different than many of the other big names in fiction. He is also entering the public domain soon – perhaps that move from creation and into the culture has something to do with it. There are many more questions to ask, many more experiments before I have eliminated all of the impossibilities I am sitting with.

In the meantime, I have been thinking back on my childhood friends, struggling to remember all of their names. If the world is bigger than I have given it credit for, then there are people out there that I have missed for most of my life. I have been wondering if I should call them up.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.