As I have written a few weeks ago, my little family and I spent most of the month of July traveling across Scandinavia. One of the highlight of that trip was, for me at least, the day of peaceful revelry in southern Sweden I spent biking around the countryside, spotting runestones, medieval churches and other heritage sites. While we spent but a single night in the surroundings, our host Hanne, my wife’s cousin took us with her to her house in Lund, further up north in Skåne.

Before we drove north, however, Hanne managed to squeeze in a stroll in the small seaside town of Ystad (famous abroad for being the location for the Wallander crime novel and film series) and a visit of the nearby Ale’s Stones. The Ale’s Stones is a site I had been peripherally aware since my college days in Iceland. I knew that it was some sort of an ancient stone monument, but remained unsure about the specifics. Yet, when reaching the site, I was able to get a better understanding why some people called the Ale’s Stones “Sweden’s Stonehenge.”

Located on a bluff overlooking the sea, the massive stones, some over seven feet (or two meters) high, form a ship-like outline more than 220 feet long (68 meters). Despite the not insignificant amount of cow dung – the site is located within a pasture – and the mass of German cruise tourists spread around, the Ale’s Stones exuded a feeling of power, reverence, and grandeur. While we are not certain when the site was built, and what it was used for, most scholars theorize that the stones were erected in the pre-Viking Iron Age, and they might have been used as either (or both) a grave or a solar calendar.

While we might never truly know, neither the heaps of Germans strolling along the boulders, nor my daughter who happily played hide and seek behind them, seemed to care. The physical site is simply alluring in its own right and I was positively surprised by the amount of people visiting it. Truly, southern Sweden is not only even richer in ancient sites than I thought, but these appear to attract quite a following as well.

The Ale’s Stones site near Ystad, southern Sweden. Photo by the author.

Alas, even if parts of me wished we could stay a little bit longer (at least until the cruise tourists vacated the premises), we had to go back to the car and head to Lund. On the way, we crossed the same patch of countryside I explored the previous night on bicycle and spotted the noble, if eerily-ominous church and castle of the Marsvinsholm peerage. Soon after, however, the landscape turned more urban and we quickly got to Hanne’s house in the outskirts of Lund. The building, located in a charming and green 1960s suburban neighborhood, is where we will spend the next two days.

Once we unpack our gear, Hanne points us in the direction of her daughters’ old room, where we will spend the night. Just like in the old cottage, the room is filled with old toys, books, board games, and so on. While we unfold an old Nordic-style wooden bed for the kid, she is hard at work walking with a small stroller where she has placed a garish elephant plushy. Just as with the previous evening, it is easy to get comfortable in such an environment and everyone manages to get a very good night of sleep.

The next morning, after feasting on some brown bread, cheese, and the darkest coffee this side of Lake Vänern, I turn to Hanne, who leads me to the garage, hands me a couple maps, a helmet, and wishes me good luck. At that point, I have already made it clear that, regardless of what happens when we visit, there is one place that I have to visit, no matter what: Uppåkra.

While not as well known as other sites in Sweden and Scandinavia, Uppåkra is one of the most significant locales for anyone even slightly interested in Old Norse religion. Not only was Uppåkra one of the largest and richest settlements in pre-Viking Age Scandinavia, but it is also one of the very, very few sites where archeologists have unearthed a building that was likely primarily used for religious purposes, like a temple: the Uppåkra cult-house.

Excavated several times in the 20th century, the site of Uppåkra was already known as an Iron Age dwelling. Then, between 2001 and 2004, a new archeological dig revealed a massive settlement. Right in the middle of the site, researchers discovered something looking suspiciously like the remains of a temple. When I was getting started with my study of Old Norse religion in Iceland, almost a decade ago, the Uppåkra cult-house was the talk of the town. I particularly recall our professor speaking about it and how it helped putting in context and explaining a lot of what was previously only known through later written sources.

A proposed design for what the Uppåkra cult house might have looked like. Drawing by archeologist Sven Rosborn. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

As I made my way out of the garage and unto a nice, flat asphalted biking path, I could feel my heart racing and a smile appearing on my face. Finally, after all these years, I was going to visit the site of what possibly was the oldest Heathen temple ever found. Thanks to Hanne’s and my wife’s magnanimity, I was given free rein to go on my own, with just one condition: that I came back for dinner. Easy enough, I thought, strolling down avenues and parks, heading for my holy grail.

Naturally, things would not go quite as planned.

While finding my way through the suburbs of Lund is easy enough, with clearly marked roads and wide biking lanes, I start double-guessing myself as soon as I arrive at the edge of the urban habitation. There is a big roundabout (or “rondelle” as those are called in Sweden) and I am unsure which exit I should be taking. To make matters worse, it had just started pissing down rain, and I cannot take out Hanne’s informative, yet highly permeable paper maps.

After a hot minute waiting for the traffic to die down, I take the first road on the right, pass an old windmill and a graveyard named after St. Lawrence before the road merges with the highway, which I took for being the European Highway 22. Alas, I had taken a wrong turn at the roundabout and was instead on the national road 108 – silly me! Uncertain about where to proceed, I cross the road and head unto a dirt road, only to realize that it is a cul-de-sac.

Wet as a rat and about as presentable as one, I go back to the highway and spot a more promising right turn. In no time, I have gotten back to a much safer bike path, but still, the heavens are beating on me, and strong winds slow me considerably.

Who said that a pilgrimage should be easy, right?

After a few long and excruciating minutes, I spot some sort of a shop, with people hanging outside. “Where is the temple?” I ask. The confused Swedes, professing not to be from there, cannot help me, so, still in the dark (figuratively and literally), I just continue straight, hoping to find some sort of road-sign to help situate myself.

While I bike, I start seeing a smidgen of blue in the sky and, almost as quickly as it started, the rain ceases. In the distance, I see a large structure with a tower and look on my map. I have no clues which of the half-dozen churchly buildings marked on the map this one could be, but if I get there I might just be finally able to see where the Hel I am.

As I make my way over to the neo-Gothic looking construction, the skies open up almost completely, and I am greeted by the warm sun. In no time at all, I see a blue road-sign on the road: [⌘ UPPÅKRA 1], and in just about a minute, I reach the walls of the church, which, conveniently enough, is located right across the road from the Uppåkra archeological center.

The church in Uppåkra, built in 1864. Photo by the author.

It is 11:30, and it took me almost an hour and a half to cover the meager five and a half kilometers (3,5 miles) separating Hanne’s house and my goal. Yet, things are looking up now. The sky is blue, the sun is shining, and I arrived just in time for the hourly guided tour of the premises. Just like back home in the museum I work at, the employees of the Uppåkra archeological center propose guided tours focusing on a variety of subjects. The tour I had arrived just in time for would be lead by Elvin, a bearded archeologist who will guide an hour-long tour about the history of the site, its importance in Iron Age society, and how it was rediscovered.

Uppåkra, in the context of the Nordic Iron Age, is something of an oddity, he tells us. If the site has revealed Stone and Bronze Age mounds, which he points towards, it truly came to be in the period known as the Roman Iron Age (the first few centuries CE), where it became the seat of an absurdly rich and powerful chiefdom. Unlike some sites that only rose and flourished for a relatively short period before being replaced by a competing center of power, Uppåkra remained one of, if not the, largest and most powerful settlement in what we now call southern Sweden until at least the early Viking Age.

As we walk across the dirt path outside the museum, he points at a distant barn, and then to a barely-visible grove on the horizon. In those times, he tells us, the settlement stretched all the way there, several hundreds yards away, the size of a dozen football fields. In some ways, one could see Uppåkra as a kind of urban settlement long before those became common in Scandinavia. In any cases, the draw of the site was so notable, that, as opposed to other power-centers of southern Scandinavia, the areas immediately outside Uppåkra are comparatively much poorer in archeological finds, indicating a concentration of power, population, and riches in the “town.”

We continue a few meters further up the path before Elvin points towards an old farmhouse. This is where, he tells us, that the archeological saga still going to this day in Uppåkra started, when, in the 1930s, a planned extension uncovered traces of a Bronze Age settlement. If the find was investigated, it did not elicit much enthusiasm and Uppåkra was practically forgotten until the 90s, when metal-detectorists were granted permission to examine the site. Assisting local university researchers, these enthusiasts soon discovered thousands of artifacts and a more proper dig was organized.

This dig, followed by another one in the early 2000s revealed the scope of Uppåkra’s power: a longhouse, kitchens, workshops, habitations of various size, and the now-famous cult house were all discovered in the span of just a few years. According to Elvin, the cult-house was located just a few feet away from a massive longhouse, which probably housed Uppåkra’s ruler, but was erected as a separate building sometime in the Roman Iron Age.

This structure, first noticed during routine archeological inspections in 2001, consisted of a series of buildings successively erected on the top of each other for a period of seven hundred to a thousand years. The building, which was supported by four massive pillars dug deep into the earth, must have been unusually tall, and measured some 13 by 5 meters (43 by 16 feet). Due to this unique construction style (which parallels the later Norwegian stave-churches), its proximity to a seat of power, and, last but not least, the trove of artifacts that was excavated from its premises, the so-called “special house” in Uppåkra soon was interpreted as a Heathen temple.

The scaled-down reconstruction of the Uppåkra cult house. Photo by the author.

In the immediate vicinity of the building, Elvin says, stood a massive heap of bones, most of which were animal in nature, with a few human skulls scattered within. This pile, he tells, has been interpreted as an offering site, where the bones of animals and humans that might have been sacrificed in the hall were deposited. Around the cult-house a great number of damaged weapons have also been unearthed. These finds are eerily similar to other contemporary and more ancient offerings of weapons and war gear, possibly from deceased enemies, that were routinely deposited in lakes and mounds.

It was inside the building, however, that the most impressive cultic finds were discovered: a set consisting of ornate bowl and beaker, gold foil figures, further bone remains, a heap of nails mysteriously gathered in a corner, as well as two figures interpreted as, respectively, Volund and Odin.

Finding such a concentration of ritual-like artifacts in a small space is, on its own, extremely uncommon, yet it is but one aspect that makes this “special building” so special. Recent digs in the neighboring long-hall indicates, for example, that while it had been burned down multiple times, and its inhabitants slain, the cult-house was never torched, possibly implying that the building was seen as a sacred space.

Finally the fact that despite years of scrupulous digging, the structure has not yield any artifact witnessing to daily life activities reinforces the theory that the building was intended solely as a ceremonial space.

While Elvin speaks, he gestures towards a grassy patch a few meters from the path, and I ask him what it is. He tells me that this is exact spot where the temple was located. After the latest excavations early in the previous decades, earth material was placed back in the trench, and the spots where traces from poles were located had been marked with short wooden stumps. As the tour comes to an end, I ask my guide if it is allowed to walk over there and he tells me there is no problem whatsoever.

After parting ways with my most excellent guide I take a little stroll through the exhibition center and take a look at the (significantly scaled-down) reconstruction of the building before heading back to the field.

The site where the Uppåkra cult house once stood. Photo by the author.

There is no one around anymore, and the sun is still shining. I step unto the grass, and after a few strides, I stand in the middle of the four wooden markers.

It is there, ten to twenty centuries ago, that the followers of the Old Religion sacrificed to the gods. Yet today, I am not standing within a high-timbered hall, but kneeling in the dirt, under the sun.

It is a peculiar feeling, being there, on ground that once was holy, and being completely left to my own devices. How should I behave? What should I do here? I feel some sort of spiritual dissonance, as if I had a foot in two realities at once, a queer feeling indeed. And yet, when I look inside myself, I feel at peace; so at peace, in fact, that I bow down, and lie down, across the length of the once-temple.

The grass is dry and warm to the touch. I hear birds singing and feel the wind humming. I feel like I could take the deepest and most restful nap of my life right here and there; alas, it might get me in trouble. Maybe I should attempt that other day, late at night, in the midst of the tranquil white nights? Imagine what kind of dreams one could have right here.

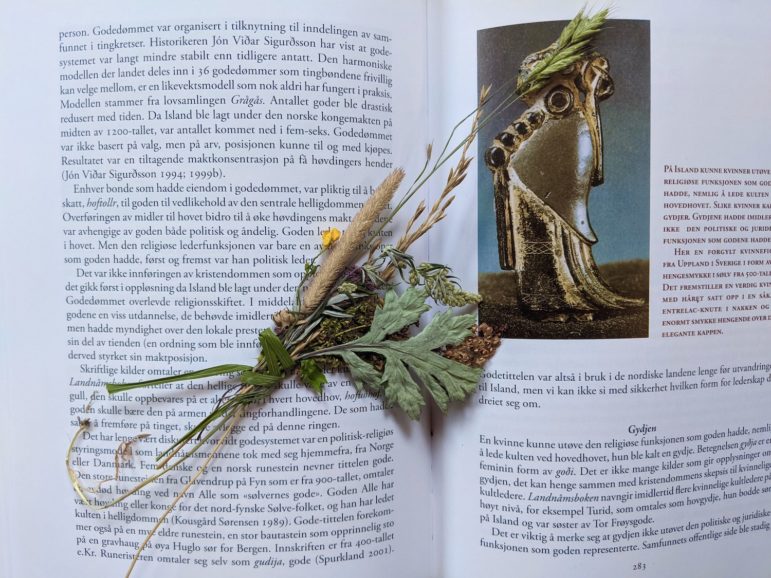

After what feels both as an eternity and too short a moment, I sit up. Even though I am pressed for time, I still am not quite ready to go just yet. I want to do something more before I leave. I sweep the tall grass with my hand and I break a single blade. In another quick swoop, I grab a thistle, a small yellow flower, and some sort of oat-like plant, alongside a few others. I bind them all with another long blade of grass and slide that innocuous bouquet into my book.

This is it, I think. I can leave now.

A bouquet made of grasses harvested on the spot where the old temple in Uppåkra once stood. Photo by the author.

As I get unto my bike, getting ready for the journey back, I take another look behind me, and I see the church again, a massive stone structure, visible for kilometers. How amusing that, a thousand years after Uppåkra was abandoned and supplanted by the newly-established Christian town of Lund, the site of its erstwhile temple still draws people from across the continent. The temple might not be standing anymore, and yet, the spectral imprint of its high timbered walls eclipses that of the house of the Christian god. This makes me feel that, even if the only thing I did today was to stand in the midst of disappeared wonder and hear tales of the past, it satisfied my intellectual and spiritual curiosity many times over.

Sometimes, when visiting vanished sites, it is easy to become saddened and overwhelmed thinking about what once was, and feel the awful bite of resentment and bitterness. Not this time, though. The temple might have left the physical realm a long time ago, but its spirit, its myth remained, both etched in the very ground it sprouted from, and in the souls of the people who have devoted years of their lives to bring back its memory, its status, and its power.

One could even say that the way these archeologists brought back this forgotten temple back from oblivion should be a source of inspiration for those among us who wish to bring back the worship of the Old Religion. Their drive, their expertise, and their dedication is a testimony that, if it is not possible to perfectly know and recreate what once was, the remains and the memories of old can be propped up and serve as a guiding light for all those who seek, and those who build anew.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.