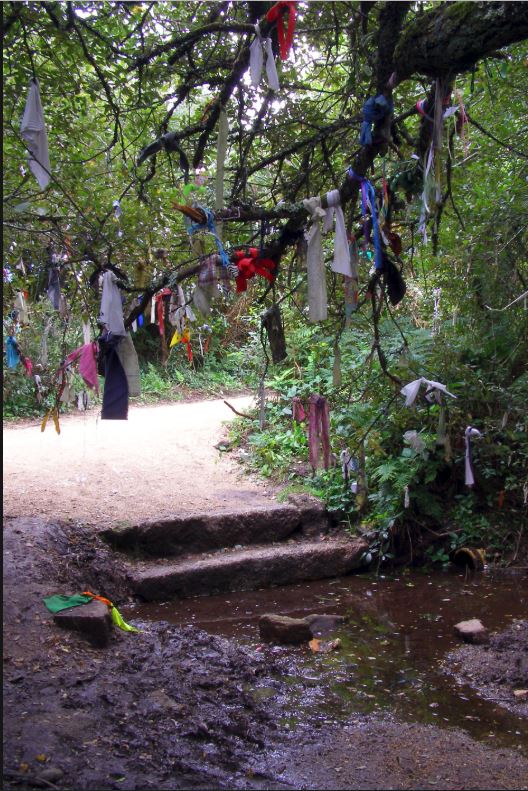

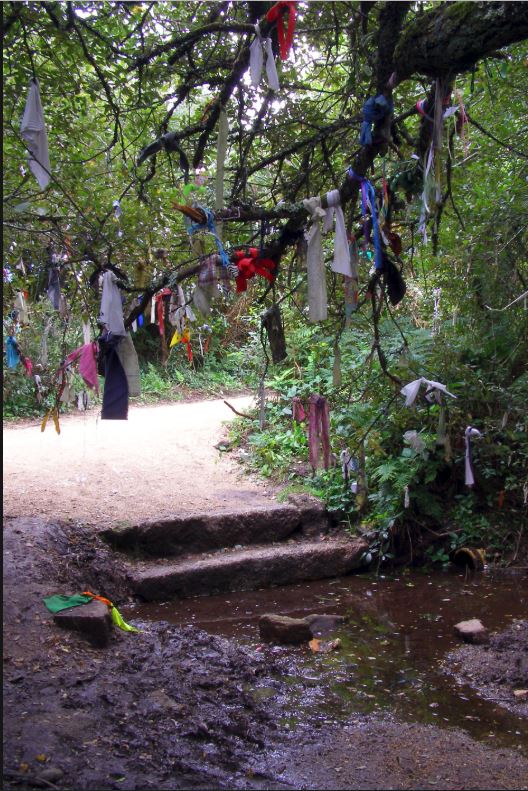

GLASTONBURY, Somerset, England – Visitors to sacred sites across the U.K., from the islands of Scotland to the sacred springs of Glastonbury, will be accustomed to seeing rags or ribbons (known as ‘clooties’ or ‘clouts’) tied to nearby trees, as a form of offering. This is an ancient practice that is found right across the northern hemisphere, from the U.K. to Siberia, and elsewhere.

In Siberia, for instance, one is supposed only to use white or cream cloth, and tie the knot of the rag in a particular direction, but customs vary, and most modern practitioners in the UK use a variety of cloths and ribbons, as well as leaving other objects around sacred sites.

At the Black Isle in Munlochy, in Scotland, this practice has been carried on for generations, and dipping a rag in the sacred well and then tying it to a tree has been a familiar part of life for hundreds of years.

Clootie Well, Munlochy, Scotland (2013) – Image credit: Dave Conner from Inverness, Scotland – CC BY 2.0

But in these environmentally conscious times, many Pagans object to the custom, especially when it involves non-biodegradable substances. Plastic strips, for instance, don’t break down, and even if people use actual cloths, these can take a long time to disappear from the natural environment.

David Alston, a local historian, explains that the idea behind the practice is that it contributes to the healing process: dip the rag in the well, dedicate it to someone in need of healing, and then tie it to a tree. As the rag disintegrates, the person will heal.

He suggests that the Munlochy healing well was originally dedicated to St. Curidan, an early Christian saint, but it has also been linked to St. Boniface, a Christian missionary in the area around 620AD. It goes without saying that these kinds of wells may have been devoted to older deities or local spirits; although we may not have evidence for this, it remains a possibility.

“In 1870 it was said that there had once been a tradition of leaving sick children here overnight – if they recovered, it was attributed to the power of the well. The problem today is that many of the cloots are of synthetic material and do not rot away as they would have done in the past. It’s still an eerie site and a reminder of how folk traditions survive and are sometimes revived.”

Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) look after this site, and organise clean-ups on occasion – the last was in 2019. The well has been cared for before this involvement, however, by locals for hundreds of years. Resident Verity Walker remembers it being cleared and trees trimmed when she was growing up in the area, and has used the well for its intended purpose herself.

“When my daughter injured her foot, I hung a sock – it has to be biodegradable and related to the part of the body that you want to recover.”

But more recently, an unknown person has organised a clean up of their own, causing controversy.

Clootie Well in Munlochy, Black Isle, Scotland (August 2019) Image credit: Sara Thomas – CC BY-SA 4.0

FLS encourage individuals to leave biodegradable offerings, such as small pieces of cloth or wool. Certainly, some of the things they’ve removed from the site are not sacred offerings – unless visitors have started treating Venetian blinds or old electrical equipment as a suitable offering!

The Guardian reports that bras, underpants, and a hi-viz jacket had been added to the more old-fashioned clouties. Fly-tipping [illegal dumping] is, of course, a problem across the U.K. But FLS are not suggesting that people take it upon themselves to clean up the site without permission, and some locals, such as Mhairi Moffat, who lives nearby, suggest that the site ought to be more formally and officially recognized.

She says, “It should be more of a landmark. It has been there for centuries. People from all over the world come to see it.”

Claire Mackay, a local herbalist, told the Guardian, “I’m sure the person who cleared up thought they were doing something good, but the fact they took it upon themselves, weren’t a local and did it without the permission of Forestry and Land Scotland has upset a lot of people.”

Local opinion, if the community Facebook site is anything to go by, ranges from suggesting that the offending cleaner ought to be cursed, to acknowledgments that the site was in need of a bit of attention.

FLS has put notices up about biodegradable offerings, and regional visitor services manager Paul Hibberd points out that part of the problem is the amount of plastic in modern cloth – this may make it durable, but that’s not great for something like a cloutie, which is intended to degrade.

Claire Mackay says, “The clean-up should have been a community decision,” she says. “But now we can treat it as a clean slate and hope it has planted that seed about the need for people to leave more natural things.”

Verity Walker adds, “It’s a symbolic act, an act of meditation and connection, an act of faith even if you’re not sure what you have faith in, and that’s only to be encouraged.”

Locals are intending to form a clean-up squad of their own and initiate a project to instruct local schoolchildren into the art of leaving votive offerings.

Elsewhere in the country, local groups have taken other approaches, such as removing clouties periodically and turning them into art forms: one such appeared at the Magickal Women Conference in London in 2019), and artist Sara Hannant has also used them.

But not all Pagans, as we’ve noted, agree with the practice. We canvassed a variety of opinions. Many expressed the opinion that even biodegradable materials were problematic and did not endorse the practice at all.

Mike Stygal of the Pagan Federation in the U.K. told us, “The environmental concerns are numerous. Non-biodegradable materials aren’t good to be left out in nature, and certainly not tied to a tree where they can strangle growth. But even biodegradable materials can cause problems for the ecosystem, potentially introducing substances that upset the balance of that ecosystem.”

Stygal added, “I appreciate the traditional nature of the practice, but on balance, I prefer the approach of leaving nothing but footprints, taking nothing but photos and memories.”

“I don’t like it at all, even if a material is biodegradable it doesn’t mean it can’t cause any harm to the local environment or animals. I’m a big believer in take nothing but memories/photographs and leave nothing but footprints,” said Sarah Kerr, who identifies as a Pagan.

Breo May, a Traditionalist Witch said, “I have a real problem with this – and a real problem with the idea that being biodegradable is always a good thing. Biodegradable materials can take YEARS and YEARS, and might jot happen in the wrong conditions. The process can leave behind toxic components – the stamp of being a biodegradable doesn’t consider this. Yes, it’s a traditional practice but that cannot be used to justify doing something that is harmful. We have to evolve and change. When you know better you do better.”

“As an animist druid, I object strongly to the tying of things to trees, in fact the leaving of offerings outdoors at all. There is a worrying disconnect between modern pagans who profess to revere the earth as deity and the anthropocentric vanity of having to put a bit of human stuff to mark their devotional territory. It is perhaps somewhat naïve to think we must make offerings out in nature, when perhaps tending to natural environments and making the ‘reverse offering’ of picking the rubbish up is likely to be looked on more kindly by a divine, aware earth,” Druid, Helen Compton said.

Some expressed the opinion it was an acceptable practice provided the items were biodegradable.

“We do them. Biodegradable material which isn’t harmful to wildlife,” writer Gavin Bone said.

Archaeologist Malcolm White said, “I don’t do it but don’t mind, providing it is natural biodegradable material.”

“I’ve only once hung something on a sacred tree! It was as a plea for healing one of my daughters (it was heard answered positively)! I used natural stuff I found close by – grass, a twig and if I remember correctly, a pebble from close by. I would not want to see clothing etc,” Pagan, Magpie Meg told us.

Still, others who endorsed the practice while using biodegradable materials also acknowledged how some of the sacred sites have ended up being misused and items left that were not perceived as being sacred offerings, leaving them somewhat conflicted on the practice of leaving offerings.

“Only 2 types of offering should be left in the wilds, a small amount of spirits poured as libation where it will do no harm, or something biodegradable and that will perhaps feed the animals – I generally will leave a small offering made of natural wheat such as in the photo. I learned how to do this on a workshop with Victoria Musson, much more meaningful and eco-friendly than some of the Cooties,” Traditional Witch Suzanne Read said.

Read continued, “TBH [To be honest], last June I visited the Clootie Well in Scotland that was recently cleared, it was not enhanced by some of the things left, a lot of man made fabrics, some of which were more litter than clootie, and although everyone has their own right to do as they see fit, it did not feel like a particularly revered or overly special place…”

Druid Tim Hawthorn expressed being conflicted, “I have mixed feelings. I think it’s a very beautiful tradition, but. I think the important word here is veneration. It needs to be done with respect and understanding. The trouble is that modern pagans have latched on to it as an idea and, as we’ve seen in Glastonbury, don’t always think their actions through or the consequences thereof. So venerating [a] tree is a great thing, but tying all manner of stuff with no regard for the health of the tree or wildlife is not appropriate and it gets a very bad reaction from more conservative conservationists. We need to be seen to have a greater respect and understanding of nature, unfortunately, the inevitable consequence of an idea becoming fashionable is that people want to join in without having any idea why they’re doing it.”

Jim Champion [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Clouties hanging from a tree near Madron Well, Cornwall. Image Credit Jim Champion – CC BY-SA 4.0

OBOD member, Sarah Thelwall recalled a similar situation that occurred in West Cornwall, “There was an issue locally, here in West Cornwall, recently. The Ancient Sites Protection Network cleared away a huge quantity of material from the Holy Well at Madron, and many local people were upset that their clouties and other objects had been removed without warning of the clearance. The cloutie-covered trees were left bare.”

Thelwall continued, “From the fuss that erupted as a consequence, it was clear that the area had become a place where people, whether pagan or not, were leaving items in memory of deceased family and friends. People argued that cemeteries would not be cleared of such mementos. It seemed many people who were leaving ribbons and other items tied to the trees were not doing so as either offerings or spells but were using ‘clouties’ as memorial items. My own view is that the planet is in dire need of our care, our respect and a move to harmonious and beautiful ways of being. By honouring nature, we honour ourselves and others.”

Daniel Owens, a folklore enthusiast, noted that the emotional state of those leaving offerings might be a factor in a lack of consideration for some of the items being left, “I chanced upon the Clootie well on the Black Isle – I am not in the habit of casually leaving or taking anything from sacred sites and I found the Black Isle site fascinating and solemnly comforting. People are often leaving offerings at these places in a state of despair or turmoil and may not be thinking clearly about the environmental impact of their gestures – I think the Fairies understand.”

However, Owens goes on to say, “I have lived for many years close to Doon hill at Aberfoyle which has become progressively more festooned with “fairy stuff’, like a pale imitation of a Disney attraction, over the years – much to the disgust of the elves, fauns, and fairies who inhabit the hill which has its own rugged beauty and sacred magic. Offerings and wishes left in good faith are another thing. I once brought a ‘wishing line’ of paper leaves, each bearing wishes from children and parents at the ‘Kidz Field’ at Glastonbury Festival (2009), to the Minister’s Pine on Doon Hill – all biodegradable and petitioned to the Fairies in good faith – It was an honour to perform the duty.