In the spring of 2011, I dragged myself from an Old Norse final into the cinema across the street from campus. I was dead on my feet, the twice-murdered victim of an all-nighter, done in by noun declension. But I was not, under any circumstances, going to miss the premiere of Thor.

This was back before I was a Pagan, when my fascination was, I thought, purely academic. I was starting to love the stories of these gods enough to write about them, retell them, to study the language they were written in. I had begun to quiz my Pagan friends about them, hesitantly exploring an idea of relating in some real way to the vibrant threads I felt in these stories. In all of this, one figure got most of my attention, and I admitted that, above all else, I was excited to see a version of him portrayed on screen.

Even sleep-drunk and loopy, I was underwhelmed by Tom Hiddleston. This wasn’t fair to him, I knew. I liked the actor, and I liked the character he was portraying – but I didn’t recognize him. Where was my gender-shifting troublemaker, Odin’s brother, the mother of monsters, the god that had caught my interest so deeply? Who was this sad, betrayed prince?

Thor, I could recognize occasionally – there was something of the myths in his brash good humor and strong, if occasionally unexamined, code of ethics. Loki, on the other hand, seemed like a stranger. I went home disappointed, crashed into the sleep of the overcaffeinated, and woke up with the knowledge that the movie I had looked forward to had nothing to do with the myths I loved.

Now, looking back with a decade of spiritual growth and media consumption, I’m glad to say that I was mistaken.

Tom Hiddleston appearing in costume as Loki at San Diego Comic Con 2013 [Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

To hear Hiddleston tell it, his depiction of Marvel’s Loki has been a mix of love and responsibility, a careful characterization informed by the mythology from the start. What I have heard from the Pagan community has been more divisive. The American Heathen community has fought over Loki for a long time, and his followers have struggled to find places where they can toast him in public. The popularity of Hiddleston’s portrayal has often been weaponized in circles where the deity is not welcome.

“Modern Lokeans – especially when dismissed more recently as ‘teenage Marvel fangirls’ by other Heathens,” my partner Bat Collazo says in zir introduction to the Loki devotional Blood Unbound, “are often stereotyped as immature, unacceptably feminine, and hyperemotional.” This stereotype has been repeated so often that it’s hard to find examples on the internet under the volume of Lokeans attempting to respond, but the shape of it is clear: someone (almost always a young girl in this stereotype) sees a Marvel movie and starts worshipping Loki without knowing anything about the original myths. Even worse, her attraction to the actor means that her devotion is sexually charged.

Questioning her relationship with the god causes her to lash out in unreasonable ways, and she stops all other practice in a community with her outspoken religious fervor. She’s a strawman to be derided, or distanced from, and never ever to be taken seriously. There is nothing in her practice that has anything to do with the myths – or so goes the stereotype.

I’ve thought a lot about this imaginary Lokean over the years. I’ll set aside for the moment the now-apocryphal story of the comics author who dreamed he was visited by Thor, Loki, and Odin while writing Thor for the first time. I’ll set aside the fact that gods are opportunistic, and that Loki’s name has been on the lips of legal experts and Lucky Charms salesmen for almost a decade. I’ll set aside the folks who, having seen the movies, went and found the myths and became “proper” Heathens, sometimes distancing themselves from the overly sexual ‘she’ of the internet.

With apologies, I’ll set aside the people who identify with some aspect of this stereotype – the godspouses, the cosplayers, and the devout whose defenses of their god are deemed too unruly. The nature of things is that this stereotype, this “she,” exists in her entirety somewhere, this young beloved of Loki, her practice based entirely on the media, her interest limited to the figure as portrayed by a long-haired British Hamlet.

And her practice is as real as mine.

This should be self-evident. Pop culture Paganism has been around since at least 2004 in its current form, and I have heard elders talk at length about the importance of Wagner, Tolkein, and even Butcher in their practice. In a world where an idea filled with intent can give rise to a form, every character is in itself a spirit. I don’t believe that I could move through these spirits without them affecting me, in some way.

The implicit judgment in the straw man of the stereotyped Lokean is that some of these stories are, for one reason or another, more weighty. Their value as spiritual guides and companions is greater because they, in themselves, are bigger than their counterparts. Smaller spirits are less important, and the idea that someone might be getting a valuable spiritual experience out of their unresearched practice doesn’t bear thinking about.

A Loki cosplayer at the Comikaze Expo 2011 [Srini Rajan, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

I can sympathize with that. In my opinion, Loki, the currently-ongoing Disney+ miniseries, is a poorly-paced, overwrought, underscripted mess. While not as bad as the bag of plot shards that made up its predecessor, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, Loki is too many good ideas with too little follow through and will not go down as one of Marvel’s greatest contributions to the culture. Watching the previews, I expected a six-hour popcorn flick at best. I didn’t expect any kind of lasting impression, at all, and it definitely isn’t a series I would have expected to sit with, nodding along in recognition.

With Hiddleston as executive producer, it’s not surprising that the show is a loving, if somewhat meandering, exploration of Loki’s character and motivations. What’s more of a shock is where that exploration takes us. The premise at the core of the season is straight out of the most over-the-top and goofy days of comics. Three beings watch over all of time, ensuring that events happen in the order they are supposed to happen, “pruning” any timeline where circumstances go awry.

Top of their list of offenders is Loki, whose mere existence seems to cause deviations from “The Sacred Timeline.” The protagonist is a Loki taken from directly after the first Avengers movie, before most of the hard-won character development of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Without his brother, out-gunned and reeling in a context he doesn’t understand, this Loki is slammed through a series of existential crises in the form of “Variants” – Lokis from other timelines who, for better or for worse, reflect him back on himself.

In this context, Loki’s characterization changes quickly. The subtexts of his struggles in the first two films – what it means to have free will, whether to deviate from or embrace the path that has been set for you, how to love yourself – are spotlighted here, in tones that grow increasingly mythic as the show goes on. One Variant finds shelter in the destruction of worlds, running from those who destroyed her family because she had the audacity to be a girl. Another builds his own Asgard, only to see it devoured, as a theme referencing Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” plays. The title “God of Mischief” is challenged, and changes, slowly, into “God of Outcasts.”

In other words, it’s downright Lokean.

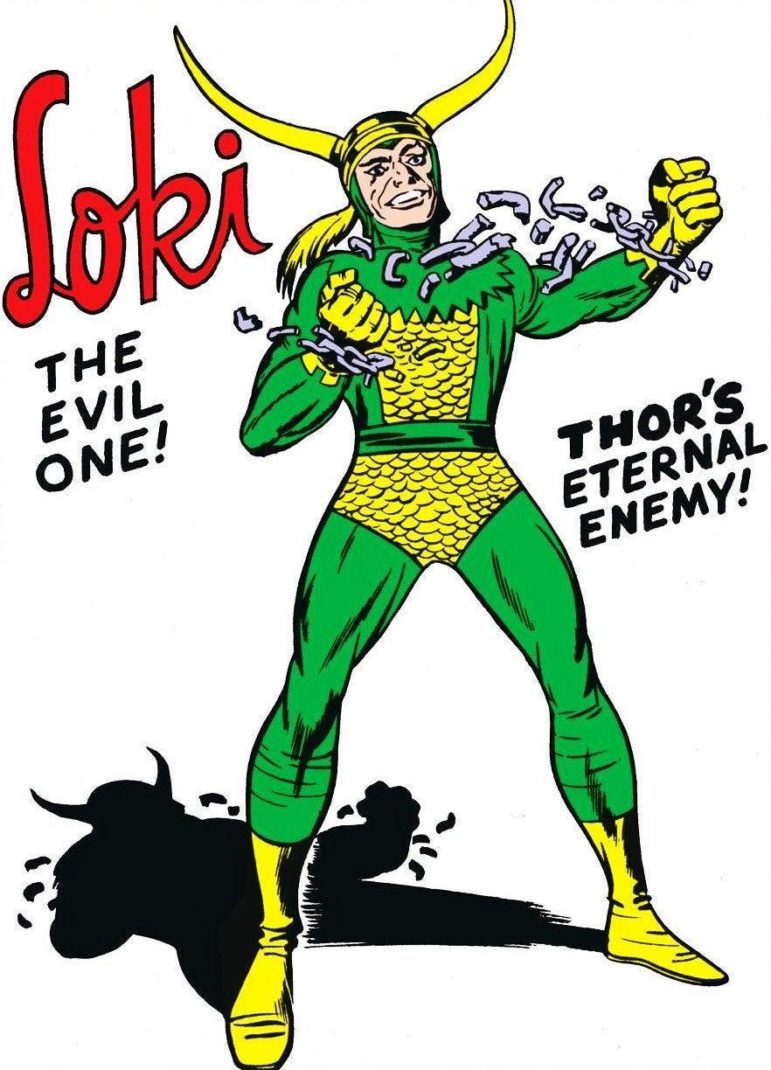

“Loki! The Evil One! Thor’s Eternal Enemy!” A classic comic book image of Loki [Marvel Comics, fair use]

It’s a little outside my paygrade to claim that a Disney property is divinely inspired. While there are moments of Hiddleston’s portrayal that strike a familiar chord, I would highly doubt that he’s a vessel for divinity, retelling the themes of the myths through the pocketbook of Mr. Mouse. He doesn’t need to be. The series is meditating on the same questions that the Lokean community asks itself, referencing the myths, winding towards a conclusion that will echo Ragnarok’s cycle due to the very nature of a franchise. There’s some meat on these glittery silicon bones.

There’s an argument to be made here that gods will take any opportunity to slide into human consciousness and make themselves known. There’s another that points out any character called “Loki” often enough will drift inexorably toward the deity, picking up traces from culture and the divine themself.

I’m not sure if either of those arguments are true. What I’m interested in talking about is a young girl who falls in love with a series about someone who is isolated and unloved, who lashes out against a fate that they do not want, who struggles to find their own worth. I’m interested in someone who sees a character love the feminine version of himself, who claims their shared sexuality, and who is moved to worship. What might this story have to offer her? What might a spirit like that be like? Where, exactly, is the line that makes it less worthy, less itself, than another experience of Loki?

In the penultimate episode of Loki, the main characters walk through a battlefield and into the city beyond, revealed only after the death of a god. I know this scene. Snorri spells it out a little differently, but it’s there in the myths, the same except for every detail. As I watched, I was sure that someone, somewhere, felt it like a revelation.

Wherever that person is, wherever their path takes them, I am glad that they have found a god that gives them meaning. We should all be so lucky.

I really hope this finale is good.

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.