Invocations, for me, are a series of names. I use names in the way I was taught, to call and to specify and to pull someone to me, a woven net of words that all mean “you.” It is half praise – an acknowledgement of the many and vast faces of the divine – and half a specifically dialed number, making sure that my call goes to the right place. Calling on names is a way to delineate a connection.

My patron has many names. I have a stack of them written on note cards, the reminders of a long-ago ritual, stacked behind his altar. I call him Roarer and Wolf’s Father, Sly One and The Burden of Sigyn’s Arms. I call him Dearest Friend and You Asshole and, now, Beloved of My Beloved, Metamour. When he answers, laughter like the crack of wood in fire, warmth like pounding blood, I know that I have called him by names that are true.

I say these names with love that chokes me, an overwhelming torrent of thankfulness and hope and blessings that have been given to me, and that now I offer back. When I look at the love I have for him and try to put words to it, they dance away, sliding out from under my hands like fish through water.

Friend, yes, but more than that. Not quite a father, although I’ve used that when other words have failed. Not quite a boss, although I’ll snark in that direction, amused and annoyed at some new task. It feels like something else – an affection beyond naming. I have never found a word that is entirely true, for him.

If Loki is my dear one, then Hermes is my first and best friend, and the one who I hope, someday, will carry me to the end of my path. Our relationship is different, just as the way my experience of the Hellenic pantheon is different from the rushing, demanding flow of the Norse. With Hermes, I have been presented choices – and I have chosen, again and again, to stay close to him. I have brought him gifts, picked because they took my fancy or they fit his style. I have offered prayers and promises in exchange for his blessings. I have learned his many names and said them sparingly, building a connection out of individual links over the course of years.

I do not need words for what Hermes is to me, because we already know.

They are laughing, daring gods, but they could not be more different when I call to them. Trying to love them in the same way would be foolish. I do not love either of them less. Hermes is the ground beneath me and the sky above. Loki is the heat and liquid that drives my body forward. They are not enough, by themselves, to balance me. I could never be in balance if I lacked either of them.

I’ve worried about that. I was raised in monotheism, and I’ve worried about showing one of them more favor, or skewing my practice in one direction to the exclusion of the other. It has been a long road to get to a place where I’m comfortable with these two relationships, the strongest in my polytheistic practice, being so different. Some days I am still self-conscious about it. Once in a while I still try to pin it down with words.

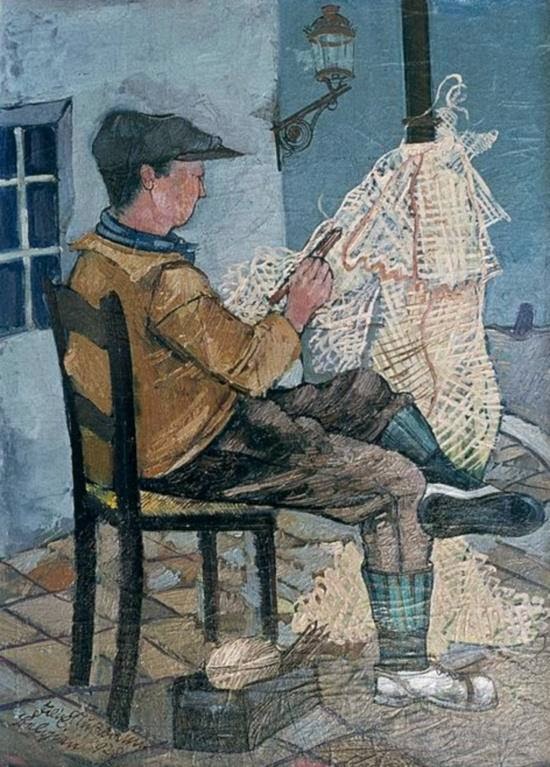

“Fishing-Net Makers,” Felix Nussbaum, 1928 [public domain]

I’ve been trying to name the ways the gods feel love for years. When I was first exploring the myths, newly out in my own queerness, I was fascinated by the transgressive and shifting nature of their relationships. Freyr and Freya were – twins? Lovers? Two sides of a coin? Loki and Odin were brothers, or perhaps dear and sworn friends, or perhaps –

I pulled different translations, researched the words, tried to figure out what that relationship would look like, what two people like that would feel. When the answer came, it was one of the first clear messages I heard from that place that wasn’t in my brain, in a voice that wasn’t mine.

“Darling, do you really think the gods have dicks?”

As divine revelations go, it wasn’t exactly the burning bush I’d been looking for, but I’ll be damned if it wasn’t effective.

My understanding of the gods is that they are individuals, unique personalities that exist discreetly and can be interacted with as people. But they’re not corporeal – and, not having bodies, a lot of the very practical human questions of relationships become somewhat moot. When two spirits are close, when they feel love for each other, there aren’t necessarily words to map that love onto. They don’t reproduce or give birth, they don’t have sex – they simply lack the capability to do so. The relationships between them are no less real for all of that.

Still, I believe the stories we tell about them are translated into human terms and, as such, are laden with translation errors. We tell stories as if they have bodies, as if they are bound by the biology of sex and the constructs of gender, because those are the stories we understand. In some ways, like all stories, they are true, but they lend themselves to all the wrong questions.

In my experience, it’s humans that need words for things. My embodiment is a great blessing, and it gives me strong and separate definitions of the kinds of love. With other humans these definitions can be important – a friend is different than a brother- but when I come to the gods they shift and dissolve. I try to move with these definitions, as I am a friend and a child and a caretaker from moment to moment. Even if I settled on one word, it would be the wrong one.

I know that this is all meaningfully and usefully true, for me. I also know it’s all a bunch of nonsense. My understanding is not universal. My sliding, nameless adoration isn’t the only way of connecting to the divine. I know someone who says “Father” and grins, all gratitude and monster blood. I know someone who says ‘Uncle’ and means it, knows the good advice and bad attitude, the slightly distant fondness. I know sisters and soldiers and step-parents, each firm in their relationship, each satisfied with the word.

And yes, I know several spouses.

An exchange of rings in Bangladesh [Jubair1985, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

I did not understand the point of channelling until last year, on a summer night in Washington, when I saw my god breathless with laughter, dancing with his family. His body was ruddy-faced and beaming with the feet-stomping, sharp-elbowed slam of a made-up dance, as he reeled us each in turn around the room. I remember feeling joy, and under it a gut-clench of recognition, a knowing that I’d felt in ritual and prayer. He was unmistakable, even wearing a face I hardly knew, and I could feel how delighted he was to be embodied.

When he let me go I stumbled over to the chairs, half-falling to sit next to a new friend. Ze looked at me, face still streaked, and we talked about him, about how good it was for zir to be able to see zir spouse, to touch him, to hear aloud how much he loved zir. “I talk to him all of the time,” ze said, beaming. “But this is – really good.”

I thought of my doubts, the way I have so often wondered if the love I feel is mutual, the way he gripped my shoulders and assured me that yes, it is. Just this once, I decided to believe him.

“I can’t even imagine,” I said, and reached out to touch zir, to steady us both as we watched him whirl past.

Ze wasn’t the first godspouse I’d met, or even the first I’d been friends with, but zirs was the first relationship I saw and recognized. We talked about zir commitment to him, the ways ze understood zir relationship – physical, emotional, spiritual – the strength and courage it gave zir. It wasn’t how I knew him, but it was the same sort of familiar. The more ze talked, the more it put me in mind of how my own marriage worked. I knew the point where romantic love, devotion, and commitment all mix to become something worth living for. I could recognize it when I saw it.

The gods don’t need bodies to be with their beloveds – but what a blessing, what a moment past words, when the immanent is made corporeal.

A couple dancing in Johannesburg, South Africa [Margherita Nel, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

I have yet to find a lesson on the nature of the gods that is not also about myself.

It took me almost a year to realize I loved zir, with zir tear-stained face and the rings ze wore for each of the gods we both considered family. The knowledge came as a building joy, a great gift with the fingerprints of the divine all over it, a shifting of friend to the promise of something else.

I have known for a long time, known since my first altar, that I can love more than one spirit, and I have learned to let those loves be different and shine no less brightly for each other’s presence. I could not love my partners as well if I had not loved the gods first.

I hold onto them with names, but I do not want to limit them or to tie them to a version of themselves that I can think I know. What I feel is not, in itself, corporeal. Now I am pushing in the other direction, allowing my defined relationships to become illuminated, expanding myself to be friend and confidante and partner and teammate. I want all of my great passions to be shifting, wordless things, slipping past language and moving toward the ineffable.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.