This past weekend saw a host of Krampus activity throughout Central Europe with more Krampus Nacht and Krampus Run events starting tomorrow and the coming weekend.

[Photo Courtesy Krampuslauf Philadelphia: Parade of Spirits 2006]

In recent years Krampuslauf (Krampus Run) and Krampusnacht (Krampus Night) celebrations and events have enjoyed a resurgence in many parts of Europe, the UK, and have become increasingly popular in North America. Krampusnacht occurs on the night of December 5, heralding The Feast St. Nicholas on December 6. The most common visual representation of the Krampus is an anthropomorphic goat, reminiscent of a satyr who has turned to the dark side.

In myth and lore alike, those who have been good can expect St Nicholas to visit and leave them a gift of some sort, but those who have been naughty hope Krampus loses their address. Folk stories tell us that Krampus brandishes a bundle switches, sometimes a large stick, or even a bag of ashes, with which to flog those who have misbehaved the previous year. Krampus, perhaps, may smear their faces with ash or cart them off to some dark place for a year or possibly forever. In all accounts the Krampus is a fearsome figure.

The specific origins of Krampus aren’t clear. In some accounts the Krampus is depicted as pre-dating Christianity and being a part of pre-Germanic Paganism, going so far as to claim the Krampus grew out of Norse mythology as the son of the Goddess Hel. There is no source material to confirm any connection to Norse mythology at all. The folklore on the Krampus varies widely depending on which country, what time period, and which author is sourced—many depictions have St Nicholas and Krampus working together as a team.

[source: Wiki Commons, public domain]

Digging into the folklore of the Krampus, there are a number of characters in a variety of European countries that are similar in function. According to Al Ridenour in his 2016 book, “The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil” the Krampus tradition seems to have been most prominent in Austria and Bavaria, being the strongest in western Austria. Ridenour cites this region as the most probable provenance of the Krampus. There are other figures like Knecht Ruprecht (German), Pere Fouettard (Alsace region of France), Schmutzli (Switzerland), and even Zwarte Piet (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemborg) that bear a striking resemblance to the Krampus in function if not always in appearance. It seems more likely that rather being an individual, the Krampus could be category or type of entity.

There are quite a few misconceptions when it comes to the Krampus, even beyond its origin. Modern depictions of the Krampus in stories, cinema, and even television help to proliferate these questionable and likely incorrect ideas to the point that even the magazine National Geographic got much of it wrong in a 2013 article, which is widely quoted and linked in other articles. Smithsonian Magazine also gets some of the lore wrong and links to the National Geographic article. Add to the mix the confusion of St. Nicholas (Catholic) and Santa Claus (Protestant) being the same and it is no wonder that the Krampus has become the Christmas Devil.

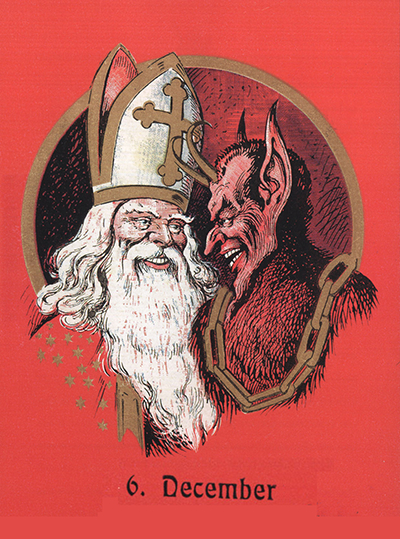

[source: Wiki Commons, public domain]

At other points in history the Krampus tradition was popular enough to even generate postcards with its image on it. Austria in 1869 became the first country to deliver postcards and by the late 1880s, Krampuskarten (Krampus cards) began to circulate. The artists who created these images were fairly influenced by both Pagan ideals and Catholic rhetoric. This might be especially true when considering that the image of Pan likely became the model for the Christian faith.

[source: Wiki Commons, public domain]

One of the possible links that Ridenour reveals in his book is the Krampus’s connection to the spirits of the dead. If you consider the origin of the word Krampus is likely derived from the Middle German word “kralle” (claw) and possibly in combination with the Bavarian term “krampn” which refers to something dried out, shriveled, and lifeless, it seems natural to draw a parallel between Krampus and the dead. In many of the stories of St. Nicholas he travels with an assortment of Krampus-like figures that appear dark and raggedy, and even mark those warranting it with ash or a mixture of ash and lard. Ridenour asserts a possible connection to The Wild Hunt, which is often composed of slain warriors or soldiers.

Whatever the origin of the Krampus, he seems to be quite literally the devil to get rid of. There are unconfirmed stories that the Catholic Church attempted to banish the tradition around the 12th century, if it even existed as such at that time. If it did exist, and the Church tried to discourage it, they were clearly not effective since the Krampus has endured. One factual account of the Krampus tradition actually being prohibited occurred in the mid-1930s in Austria under the Nazi Party. In the 1950s the Austrian government probably fueled by a religious faction, issued pamphlets proclaiming “Krampus Is an Evil Man.” That effort was short-lived since towards the end of the 20th century, the Krampus was back again and has been gaining popularity.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.