“All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.”

—W.B. Yeats

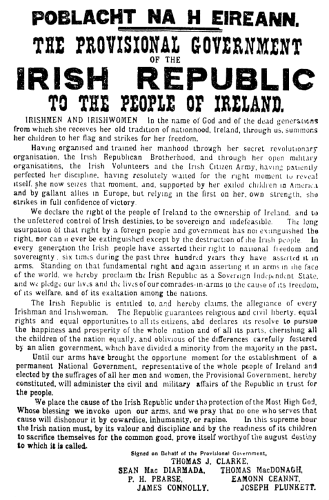

Easter Proclamation of 1916. [Public domain.]

I interviewed P. Sufenas Virius Lupus and Morpheus Ravenna, two Polytheists living in the United States who worship gods and heroes of Irish origin, to ask their thoughts about the centennial of the rising. I also contacted two Irish Pagans who I was told had expressed interest in participating in the interview, but as of time of publication, have not yet received responses to my questions.

HC: Do you honor any of the individuals or groups who participated in the Easter Rising of 1916, religiously or otherwise? How do you frame that honoring or veneration? Do you have any plans for the 100th anniversary of the rising that you wish to share?

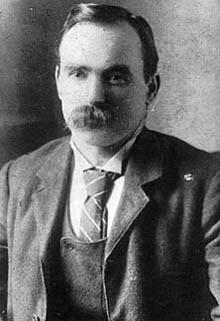

PSVL: Padraig Pearse is one of the Sancta/e/i of the Ekklesía Antínoou, whom we honor for a variety of reasons: his dedication to the revival of Irish culture, his role in the fight for Irish independence and freedom and his heroic death in that struggle, and also because he is what might be considered “queer” in our own terms, despite being celibate for life (to everyone’s current knowledge). He is not an entirely unproblematic figure in any of these regards, certainly, but very few of our Sancta/e/i are, and while I’d prefer not to focus on those problematic aspects at present, nonetheless I think this bears mentioning lest anyone think we have any illusions in this regard. I plan to not only mark the occasion “officially” in April, as many will be around the world, but I also plan to visit the GPO in Dublin on March 21st when I am in Ireland for a conference this year. I carry a coin in my pocket on a daily basis — which I also do for various other deities and hero/ines as a reminder of my devotion to them – -that has Cú Chulainn on one side of it and Padraig Pearse on the other, which was a commemorative piece of currency issued in Ireland in 1966; I will likely see if I can get something similar while I’m in Ireland this year, too, so that I can gift them to others who are engaged in cultus to various modern Irish heroes, Sancta/e/i, and to Cú Chulainn (if indeed they are engraved on the same pieces once again!).

Padraig Pearse. [Public domain.]

HC: The relationship between a specific land and the members of cultural diasporas originating in said land is always complicated, but especially so when there are ongoing political conflicts and/or struggles for cultural preservation and survival being considered. Can you speak to that, specifically with Ireland and the 1916 rising in mind?

PSVL: I’ve always found the relationship between Irish-Americans and actual Irish history and politics to be even stranger than the relationship between the people of Ireland in modern times and their own history, culture, and mythology. On the one hand, Irish-Americans are deeply invested in “all things Irish” a great deal of the time, and their ancestry is a source of pride, which comes about from the very deep and hurtful persecutions they endured when they came to the U.S. in the post-Great Hunger period of the mid-1800s and the resulting defiant psychological stance as coping mechanism in which this can result. On the other hand, there is a great deal of misinformation, ignorance, and even a lack of desire for getting to know things better amongst Irish-Americans, which no doubt springs from similar situations, in which Irish culture, the Irish language, and other things were taken as “backwater” and detrimental baggage for their lives in the diaspora, especially in British and British-influenced cultures like the U.S. of the 1800s happened to be, and the internalized shame the persecution of Irish culture created. If it’s a leprechaun (or maybe a banshee), green beer or corned beef and cabbage, Irish-Americans love it and eat it up; if it’s Cú Chulainn and Finn mac Cumhaill, Guinness and real Irish whiskeys, or soda bread and boxty, one is likely to get as little interest in these things amongst Irish-Americans as amongst the non-Irish. While 1916 represents “Irish freedom” and “Irish independence” to a large extent for some Irish-Americans, it often does so in a vague fashion, and apart from mentions of it in The Cranberries’ “Zombie” and perhaps the folk song “The Foggy Dew,” the realities of the situation and the aftermath of it are far less clear in many people’s minds. As an undergraduate, I was invited to my college’s Irish-American Student Organization trip into New York City for an “Irish cultural fair;” it turned out to be a Sinn Féin rally. To say that these things are quite different from one another, and that many people who went didn’t seem to understand that there is a difference, is an example of how difficult this situation is for many Irish-Americans, I think, is an understatement, but it is an understandable error, since coverage of Irish and Irish-American history is seriously lacking, even at the collegiate level, throughout the U.S.

MR: One of my Irish friends, in a conversation about Ireland’s history of resistance, commented to me that there was only ever one invasion, the Norman invasion from Britain, and that all the subsequent conflicts up through to the struggle for independence in the 20th century had been the continuation of that conflict. Looked at from this perspective, you can look at the Easter Rising and the Irish Revolution as the fruit of centuries of resistance. I also observe that the foundational tales and sagas that we as Celtic polytheists look to for our mythology (the Book of Invasions, the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, etc.) carry this strong theme of invasion and conflict for sovereignty, and that many of these foundational stories were committed into written literature from the oral tradition during the time period of the Norman conquest, when the people of Ireland were themselves living through a period of invasion, resistance, and conflicts for sovereignty. So this theme seems deeply ingrained in Irish spirituality as we know it today. I’m not sure you can separate Irish culture and spirituality from the historical experience of resistance.

I’m a practitioner of Celtic polytheism drawing deeply on Irish culture and history in my practice, but I’m also very aware that I’m not Irish-born, and have not lived their experience nor been part of that landscape. I’m a product of a different history. I think as members of a devotional diaspora we have to tread very carefully around this. It’s natural for people like me to have feelings and sympathies that align us with one side or another in political conflicts like the struggle for Irish nationalism, but I think we need to practice a lot of discernment about how we act from those sympathies, and to ensure that we’re not projecting our own ideas as outsiders into their struggles. I feel a lot of sympathy for the notion of Irish liberation from British rule, but I also know it’s a very complex situation that I can know only the barest outlines of. So when it comes to ongoing political issues in Ireland, I regard it as my role to support my Irish friends in their understanding of their own sovereignty.

![[Courtesy Photo Brennos Agricunos]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Cuchulainn-and-Crow-375x500.jpg)

Cu Chulainn statue with crow on shoulder, General Post Office, Dublin [courtesy photo Brennos Agrocunos]

The occultist and poet William Butler Yeats, who did not participate in the rising, wrote in his poem “Easter 1916” that after the rising, “All changed, changed utterly:/A terrible beauty is born.” Yeats admitted that he had had personal conflicts with one of the leaders of the rising, but acknowledged that by his deeds, “He, too, has been changed in his turn.” And echoing Pearce’s words about Cú Chulainn, Yeats asked of the rebels, “And what if excess of love/Bewildered them till they died?” To my mind, all of these quotes speak to a certain transcendent quality of the Rising that is difficult to pin down to any single religion or ideology. Does the heroism of the rising inform your own spirituality? Do you see a relationship between your gods and powers and the rising?

PSVL: The planners of the Easter Rising did their actions on that date very intentionally, and with superlative symbolic purposes in mind, by foregrounding the implied hope and renewal of Christian resurrection and the necessity of redemptive death in that process. However, symbolism of death and resurrection, even for redemptive and what can be called a “salvational” (but in a non-exclusively Christian valence) purpose is not unknown to polytheist religions throughout the world. I think it is probably more accurate to discuss any and all manifestations of Christian symbolism, thought, and practice from Ireland, from the fifth century up to the present, not so much as “primarily Christian” but as more “primarily Irish, secondarily/incidentally Christian,” since Irish Christianity always had (and still has!) things about it which are very different in comparison to the expected orthodoxies of Roman Catholicism.

I suspect that the great Irish heroes and deities were not “behind the R\rising” in a motivational sense, so much as very happy to support and participate in it with their descendants. Cú Chulainn and Finn mac Cumhaill, in addition to being idolized by Pearse and others, now both have some degree of public cultus in Ireland that they might not have had otherwise, and that has a knock-on effect for other divine beings in the Irish cultural sphere as well. Everlasting fame is an essential part of the Irish heroic ethos, and not only those who participated in the Easter Rising on the human level, but some of those on the divine levels as well, have reaped the benefits of this ever since.

MR: I didn’t connect my own spirituality to the Easter Rising much at all before visiting Ireland last year. I understood that for its participants, the rising carried these very Irish mythic themes of heroic valor, struggle for sovereignty, and sacrifice for one’s people. But until I spent time in Ireland, the rising itself didn’t figure directly into my personal practice and relationships with my gods. While there, I began having very distinct experiences with the gods, ancestors and Irish warrior dead that really centered that sense of the heroic, transcendent meaning of the rising, much more so than I expected. In Dublin, I was profoundly affected being at the battle sites, where the bullet holes can still be seen in the buildings and statues of O’Connell Street and other places. I very much felt the gods of Ireland, and the heroes of the rising, in strong and vocal presence there. I also experienced very vocal presences at the site where earlier resistance fighters had been executed, in what’s now St. Stephen’s Green. What became apparent to me in these places is that for the gods and the spirits of Ireland, this isn’t just history. It isn’t over. There is a sense of that same spirit of transcendent heroism waiting for its next moment to flower.

![Bullet hole from 1916 on O'Connell Monument [Courtesy Photo Brennos Agrocunos]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/OConnell-Monument-375x500.jpg)

Bullet hole from 1916 on the O’Connell Monument [courtesy photo Brennos Agrocunos]

HC: Cú Chulainn imagery has also been used by Unionists as a symbol of “Ulster’s defenders.” Obviously, this particular conflict is occurring more on the level of political propaganda than of Polytheist theology, but both sides of a given struggle claiming relationship with the same power happens to be a particular interest of mine. Do you see any theological implications in this conflict?

PSVL: I suspect that from the viewpoint of Irish heroes like Cú Chulainn, “fame is fame,” whether it is from one’s allies and devoted descendants or one’s adversaries, and in terms of his own associations and how these line up or don’t line up with modern political movements and governmental edifices, no one has a monopoly on these or a clear alignment one way or the other. “Unionist” and “Republican” have no meaning when applied to Cú Chulainn, even if “culturally Irish without foreign domination” (which would imply Republicans) and “the Ulaid” (which could imply Unionists) might apply to him. While there are traditional symbolic associations of the province of the Ulaid with “battle” in medieval Irish texts, some of which are held in high regard by modern practitioners of Irish forms of polytheism, I don’t think it is necessarily responsible nor required to view these symbolic associations as in some sense prophetic, divinely ordained, or in any way significant; especially if the people making such associations are not living in Ireland, and particularly in the areas of Ulster which have been most deeply impacted by these recent realities of violence and oppression.

HC: Fredy Perlman has brilliantly critiqued “The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism” for its premise that “every oppressed population can become a nation, a photographic negative of the oppressor nation.” He observes that “nationalism continues to appeal to the depleted because other prospects appear bleaker. The culture of the ancestors was destroyed; therefore, by pragmatic standard, it failed; the only ancestors who survived were those who accommodated themselves to the invader’s system.” Perlman was a vociferous critic of the “pragmatic standard” that he identified. As members of religions and spiritualities who do see value in “the culture[s] of the ancestors,” do you have any thoughts on this quote?

PSVL: I think Perlman’s observations are poignant; and yet, the notion of “failure” is somewhat problematic when applied to a lot of these situations, especially in mythic contexts. Heroic individuals do not get to live happily ever after; no true hero of Irish myth has their life end on a deathbed of an illness surrounded by adoring friends and family. An early death is often the lot of the hero, as the case was with Cú Chulainn. From a certain modern perspective, including those that can exist amongst modern polytheists who draw on Irish cultural elements for their inspiration, there is a deep misunderstanding of this reality, and thus a great lack of comprehension about what constitutes failure and thus what constitutes success as well. This is why so many people think that Cú Chulainn was “punished” by his death for transgressions against The Morrígan, which is as far from the reality as it is possible to get in many respects. Cú Chulainn knew what was in store for him the moment he committed himself to the warrior’s path at age seven, and his own heroic death was not a failure or a lapse in any way, it was a triumph toward which he looked forward. While this might even seem more bleak than what Perlman discusses, I think it’s important to realize this when looking at Irish — and, for that matter, any and all — premodern cultures. The appeal of some of these premodern cultures’ imagery and standards and legacy for oppressed peoples seeking nationhood is not something that can be critiqued, I don’t think, but it is also something that requires a nuanced understanding of which not many people might be capable, especially if they are not directly involved in the situations concerned and have no investments in those identities.

MR: I think there are some very problematic assumptions in this statement, both generally and with regard to the Irish nation and culture. First, I think a lot of Irish people might disagree with the notion that the culture of their ancestors was “destroyed.” This begs the question, “which ancestors?” The modern Irish population contains interwoven ancestries from the early indigenous pre-Celtic population, the Celtic or Gaelic Irish, the Vikings, the Normans, the Scots, and more. Which ancestors would we be thinking of? If the focus here is the Celtic Irish, which is what people tend to think of in terms of Ireland’s pagan past, I still don’t think it’s clear that that culture was totally destroyed. Very strong elements of ancestral belief and practice persisted in Ireland right through the Christian period and continue today, just as we often find that folk belief and practice preserve deeply pagan elements within monotheistic cultures everywhere. Ancestral folk practices like this often persist even through conquest because they provide meaningful benefit to the people, and because they tend to be far less visible than public religious ceremony. Far from being evidence of failure, it is precisely this deep resiliency and ability to persist that makes ancestral culture a source of strength and support for populations who are in a position of struggle against colonialism, erasure, and subjugation by a dominant power. The notion that “your culture, gods and traditions must be weak, or we would not have been able to conquer you” is imperialist thinking; traditional cultures would tend to measure the value of ancestral culture differently.

HC: Dominic Behan’s song “Come Out, Ye Black and Tans” links the Irish struggle against the British army and its auxiliaries to other colonial wars waged by the British:

Come tell us how you slew

Them old Arabs two by two

Like the Zulus they had spears and bows and arrows,

How you bravely faced each one

With your sixteen pounder gun

And you frightened them poor natives to the marrow.

Do you see connections between the Irish struggle and other struggles against colonization? If so, does this have an impact on your religion or spirituality?

James Connolly. [Public domain.]

MR: I do see parallels between struggles against colonization and imperialism throughout the world. The notion of the sovereignty of a people -– the relationship between a people, its native landscape, its governance, and its autonomy relative to other peoples –- is deeply embedded in Irish myth and history, and this theme is articulated again and again in Irish literature from early mythology to works of modern literature. But these are themes that play out everywhere in our world. On the American continent, we have seen a resurgence of the language of sovereignty in the current struggles of indigenous/First Nations people against their continued erasure and subjugation by the United States and Canadian powers. The Idle No More movement speaks of sovereignty in strikingly similar terms to how I have seen it framed by Irish people in their experience of resistance. I think it’s interesting that in both of these cases, these struggles are seen by a lot of mainstream people as artifacts of history, as conflicts that came to a head and ended in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but when you talk to Native people here and Irish people, it’s clear that these struggles are not closed by any means.

For me, as a dedicant of the Morrígan and a practitioner of Celtic polytheism, this does impact my spiritual and religious life. Sovereignty as a spiritual principle and power is hugely important in my religious worldview, arising from Celtic traditions. In my understanding of the Morrígan’s role, She acts as a guardian or protector of sovereignty, and in support of the warrior function whose role is also to safeguard their society’s sovereignty. I can’t compartmentalize sovereignty as if it only existed in relation to individual personal sovereignty, and I can’t restrict it to the abstract. To fully engage with this crucially important aspect of my spiritual life, I have to also recognize it and engage with it in the world around me – in the political life of my own society, and that of others in the world.

HC: At his funeral oration for O’Donovan Rossa, Pearse said, “They [i.e. the English government] think that they have pacified half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have provided against everything: but the fools, the fools, the fools! — they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.” This reminds me of Walter Benjamin’s observation that “not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious,” which I always pair with his thesis that the spiritual dimension of class struggle “will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question.” Any thoughts on the relationship between the dead and the longevity and continuity of social conflicts?

PSVL: Interestingly, Chief Seattle’s 1854 Oration seems to have some similarities with these statements as well, and many Irish people ended up in the state of Washington in the late 1800s! I would not want to state anything categorically either way on this question, since I do not speak for the dead in this case; but, I don’t think the two can be separated — easily or otherwise — either. Ireland’s past, though — in terms of its ancestors, its deities, and its land spirits — is not quiet and never will be. I think it is no coincidence that the economic crash of 2008 impacted Ireland quite severely, and it fared worse than many other nations in Europe under those circumstances, and not long before that, the Irish government built a motorway through the Tara-Skryne Valley (the very seat of the sovereignty of Ireland) and destroyed many archaeological monuments of significance in the process. If the people of Ireland and their governments, as well as Irish-Americans and other Irish abroad in the diaspora, don’t wake up to the relevance and persistence of their heritage, I foresee things like this continuing well into the future. The dead may not have the final say on many things for the living, but to ignore that they have any say at all in our lives is a grave error, I think.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Pingback: The Wild Hunt: 100th Anniversary of the Easter Rising | Heathen Chinese

Discovery of an ancient grave, under an Irish Pub unearthed on the property in 2006, gives us a hint at the nature of the people here in Ireland before the Celt invasion, and early people in England and Scotland. You might find this article interesting.

A man’s discovery of bones under his pub could forever change what we know about the Irish

The Washington Post

Peter Whoriskey

———–snip—————–

Yet the bones discovered behind McCuaig’s tell a different story of Irish origins, and it does not include the Celts.

“The DNA evidence based on those bones completely upends the traditional view,” said Barry Cunliffe, an emeritus professor of archaeology at Oxford who has written books on the origins of the people of Ireland.

DNA research indicates that the three skeletons found behind McCuaig’s are the ancestors of the modern Irish and they predate the Celts and their purported arrival by a thousand years or more. The genetic roots of

today’s Irish, in other words, existed in Ireland before the Celts

arrived.

“The most striking feature” of the bones, according to the research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science journal, is how much their DNA resembles that of contemporary Irish, Welsh and Scots. (By contrast, older bones found in Ireland were more like Mediterranean people, not the modern Irish.)

——————-snip——————–

http://tinyurl.com/h4ssrlg

I was reading this article a couple of days ago – really interesting, though I thought the invasion idea was already debunked and it was a ‘cultural’ invasion rather than a people/genetic one. Anyhow, all really groovy.

No disrespect intended, but I find it very funny that this post is by a Chinese-American writing about the Irish. As they say, only in America! 🙂

It would have been cool to also get some Irish polytheists to be involved in this too.

Not to denigrate Irish and Celtic paganism, but then, it is to be expected from the same guy who elevates an emperor who committed genocide against the Jews to denigrate Christianity and particularly Roman Catholicism. Irish first (which P. Sufena claims it is the Celtic pagan identity), Christian second? And Irish Roman Catholicism having aspects not expected from Roman Catholic orthodoxy? What the hell is this?

So somehow Celtic paganism, which wasn’t obviously practiced by this people and hardly invoked at all (again, not saying this to denigrate Celtic paganism, just pointing out this undeniable fact: Irish revolutionaries were not invoking the ideals and symbolism of the Celtic Cycles, at least not nearly as much as Christianity) is the more important cultural influence of Irish revolutionaries? This people equated being Irish with being a Catholic Christian, for crying out loud. If anything, they subordinated Irishness and Celticity to Christianity, not the other way around as P. Sufena claims or at the very least implies.

And I don’t know why elements Irish Catholicism has that makes it different from standard Catholic orthodoxy. The Celtic cross? There are different crosses in different parts of Europe; Ireland and the Celts in general are not unique in this. Gods and goddesses converted into saints? Again, a practice that even predated the arrival of Christianity into Ireland and other Catholic Christian countries have done this as well. Pagan rituals absorbed by the Church? The same happened with the Germanic tribes of continental Europe. There are unique things about Irish Catholicism, but there are unique things about Catholicism in each different region of Europe anyway. In other words, there is nothing deviant of orthodoxy just because of these Celtic aspects in Irish Catholicism. .

Thank you for these comments

🙂

Pingback: Redemptive Death and Such… | Aedicula Antinoi: A Small Shrine of Antinous

Pingback: A Druid’s Web Log – Spring has Bloomed! | Ellen Evert Hopman