Encompassing over 470,000 square miles and boasting close to 1,750 miles of coastline on two oceans, South Africa is the 25th largest nation by area, and 24th largest by population. The term “Pagan” was all but unknown there prior to 1994, at which time the same constitution that lifted the apartheid system of racial segregation also provided for freedom of religion. Since that point minority religions, such as those within Heathenry, Wicca and others associated with Paganism, have been adopted by a growing number of people, modelling — and sometimes adapting — practices more common in the northern hemisphere.

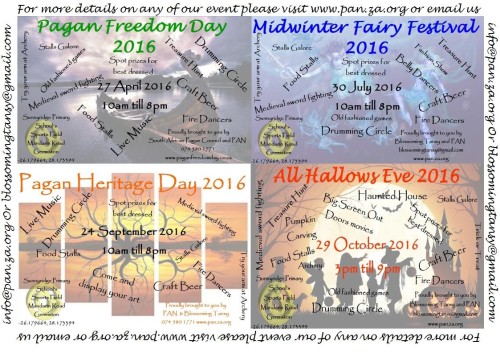

One group that is active in promoting Paganism in South Africa is the Pagan Assistance Network, which has been putting on a growing number of annual events. A quick look at PAN’s calendar shows how adapting wheel-of-the-year holidays for the southern hemisphere doesn’t always result in a complete reversal. While their Midwinter Fairy Festival takes place during the northern summer solstice, the Samhain event, which has since been cancelled, was set for October 29. This scheduling suggests that cultural influences — such as trick-or-treating — exert as much of a pull on these relatively new practices as the changing of the seasons.

One group that is active in promoting Paganism in South Africa is the Pagan Assistance Network, which has been putting on a growing number of annual events. A quick look at PAN’s calendar shows how adapting wheel-of-the-year holidays for the southern hemisphere doesn’t always result in a complete reversal. While their Midwinter Fairy Festival takes place during the northern summer solstice, the Samhain event, which has since been cancelled, was set for October 29. This scheduling suggests that cultural influences — such as trick-or-treating — exert as much of a pull on these relatively new practices as the changing of the seasons.

Ryan and Luna Young, regional organizers for PAN in Johannesburg, described the concept:

We have four days a year that we celebrate and gather Pagans and like-minded people for a day of fun and give our community the opportunity to meet other like minded people.

The first day on our calendar is Pagan Freedom Day. This is celebrated on the 27th April of each year, on our National Freedom Day [which] represents the first post-apartheid election that was held on this day in 1994. As Pagans we celebrate on this day as it is a day also given to all South Africans no matter race, gender, or any other classification. They are free to be. The event was started with unity in diversity in mind, and is the biggest day on our calendar. It is celebrated with live music, archery, medieval sword fighting, ancient games and activities. The day is ended off with a fire display and a drumming circle.

Medieval-style activities are used frequently in celebration. Ryan Young offered some details about the nature of the local traditions which have led to that overall tone. “We, my wife and I. . . and our medieval fighters are for the most part Heathens, and [sword fighting] is our way of including all the different Pagan paths. We are fortunate to be blessed with a rather large assortment of different paths here, Wiccan, Druidic, Heathen, Egyptian, eclectic, vampiric, solitaries and so many others. We do our utmost to include all paths into our events. Every year we add on a bit more than the year before. In this way the events grow, as does the attraction value.”

Drawing together people from a variety of paths for a public gathering shows how much has changed in the ten years since Pagan Freedom Day was adopted. From 1997-2007, Annika Teppo studied South African white Neopagans. She found that this group mostly avoided public rituals and often avoided even interacting with one another. In her paper, “My House is Protected by a Dragon: White South Africans, Magic and Sacred Spaces in Post-Apartheid Cape Town, she describes her interviewees as preferring to meet online, to gather in private homes, or most frequently to just go it alone:

A ‘solitary pagan’ is someone who practices alone. They do not ask others to join their rituals, nor are they willing to give detailed descriptions of their own practices. They are wary of pagan circles, as they fear that some individuals might want to benefit from them financially, or might want to involve them in power struggles —- a phenomenon globally connected with neopagan movements and known as “witch wars.”

Some of my informants divulged that they were or had previously been solitaries simply because they found ‘pagan politics’ too difficult in Cape Town. My informants’ unanimous opinion was that organized neopagan groups or covens are prone to squabbling —- which can be both fierce and malicious. I could seldom conduct an interview without the issue of ‘pagan politics’ surfacing. Those working in covens were also aware of the dangers involved and wanted to avoid them.

Teppo’s research was not only conducted over a number of years, it was also performed solely in Cape Town, which is nearly 870 miles from Johannesburg, the country’s largest metropolis and the place where PAN conducts its events.

Continuing with the description of the four PAN events, Ryan Young said:

The second day on the calendar is Midwinter Fairy Festival, and it is celebrated on the first weekend after the midwinter solstice. This event is organized by Blossoming Tansy in conjunction with PAN. The day is celebrated with everyone dressing up as the fairy folk, and concentrates on the more charitable work where we raise funds for charity organizations, be they for animals or humans. The event is ended also with a drumming circle and fire display.

Our third day on the calendar is Pagan Heritage Day and is organized by PAN in conjunction with Blossoming Tansy. With this event we concentrate on the arts and crafts of the Pagan community, giving our artists the opportunity to display their paintings and crafts. Otherwise, the day’s activities include live music, medieval sword fighting, ancient games and activities like Viking chess, toss the kaber and so forth, and as always ends with a drumming circle and fire display.

Like Pagan Freedom Day, Pagan Heritage Day is part of a wider celebration, in which “all South Africans across the spectrum are encouraged to celebrate our culture and the diversity of their beliefs and traditions, in the wider context of a nation that belongs to all its people.” Then, finally there is “All Hallows Eve.” Although it was ultimately cancelled for this year, Young had already provided a description of the final of the four events:

Our last and newest day is Old Hallows Eve. This is a new one that we have started and will be held on the 31st October and will be slightly different from the others, in that we will be starting later in the day and will be having trick or treat, an outdoor theater showing old horror movies, and on the other side of the field a drumming circle and fire display. And what is Halloween without costumes?

Halloween, at least as it’s celebrated in the United States and other northern countries, presents endless opportunities for Pagans to confront familiar stereotypes of witches as ugly, malicious women, known for terrorizing children and duping peasants in European fairy tales. In Africa, however, the word “witch” is not so easily dismissed as myth by the overculture. Damon Leff, a former director of the South African Pagan Rights Alliance, explained:

In every African country, including South Africa, the word ‘witchcraft’ refers to the negative use of magic to cause harm. It has no positive usage or definition amongst Africans. South Africa is the only African country that I know of where the term’s negative usage and definition is being contested by actual Witches. We (SAPRA and the SAPC) are also legally challenging the constitutionality of the 1957 Witchcraft Suppression Act which (although it does prohibit accusations of witchcraft) also prohibits any knowledge or practice of witchcraft.

Teppo found this to be the case, as well:

The distinction between healing and witchcraft is of fundamental importance in this worldview. In the wrong hands, knowledge of invisible forces and muthi, traditional medicines, can cause death and destruction, but in the hands of a benevolent healer, or a sangoma, this knowledge can cure illness and protect people from harm. Witchcraft holds no such ambivalence: it is always evil, an antithesis of everything sacred or commendable. A witch is any person who uses muthi or his knowledge of the occult to harm others.

Moreover, Leff suggests that many Pagans are not interested in readily accepting this widespread definition of “witch” and continue in their attempts to reclaim the term. This particular issue also points to a cultural and racial divide that is, in part, specific to this country. Teppo explained:

Many Wiccans prefer to call themselves ‘witches’, which has been a root of confusion and misinterpretations, and has divided them into two different camps in the United States. In South Africa, the term is even more controversial. In most of the African cultures, a witch is a malevolent character, truly feared. Among black South Africans, witchcraft means something irrevocably evil and horrifying. This perspective also prevailed for centuries in Europe and the United States, where being a Wiccan is still rather marginal despite Wicca’s recent popularity. … In the African systems of belief, a ‘good witch’ does not exist.

Teppo follows up with an observation by one of her Wiccan informants, who explained the problems with terminology:

In Wiccan terms witches are light-workers, terms that we are proud to use (…) However, our neighbours in this same country, the traditional African pagans, use the same terms in a very, very different, horrible connotation. A witch is often the person that all sorts of misfortunes are ascribed to… It is most unlikely that we are going to change [this perspective] … it is too deeply ingrained in the language, you cannot take it back any more… The white witches of this country, who are proud of the term, are also not prepared to give up these terms. (Female, 37)

While, as Teppo notes, the controversy over the word “witch” is not as intense in the United States, it still remains a challenge the two Pagans communities share to some extent. Another is the relationship with indigenous practitioners. In both countries, there are some people who cross that cultural boundary with mixed reactions, and there are those with a desire to include indigenous traditions under the Pagan umbrella, which is not typically welcome. Teppo quotes a member of one Pagan group who wishes to bring two paths together:

The cornerstone of this temple is rooted in a futuristic idealism to marry and integrate aspects of African pagan paths’ tradition with those of the current practice of Wicca. Everyone who joins our temple knows that they should not join the temple if they do not prescribe to the idea. – Andi Fisher, Temple of Ubuntu.

Fisher’s use of “pagan” in reference to African religions does not appear to be the norm. Leff observed that “. . . people engaged in African traditional religion/s do not self-identify as Pagans, nor as pagans, through their own choice; the term ‘pagan’ was used to label African religious practices under colonial and National Party rule, and it’s a term practitioners of indigenous religions refuse to embrace. In the South African context, Paganism (neo-Paganism) and Traditional African Religions are two separate religious identities. This, despite the very obvious similarities between them in both belief and ritual and magical practice.”

Additionally, it is important to note that, because of the scope of Teppo’s work, her informants were mostly white. As a result, the reasons why black South Africans might not be drawn to modern Pagan religions could only be inferred.

Despite sincere attempts to rise above the racial divide that separated South Africa for decades — including a groundbreaking Truth and Reconciliation Commission to mend those wounds — there remains quite a bit of self-segregation in this country, and Paganism has largely fallen on the white side of the fence. It’s a fact that Leff is also unwilling to deny. However, he’s quick to point out that it’s not the whole picture.

I think there is lingering “racial tension.” Although the system of apartheid has been removed, the effects of that system remain ever present in society. We changed the political system, not people’s prejudices. That said, many South Africans of all ethnicities have and do work together to make our country better than it was.

Harmony is a constant tension between opposites.Sometimes that tension slips one or the other way, only to be re-centred on an external value, whether common interest or legal principle. Our countries share many of the same ideological “conflicts.” Our legal and constitutional systems appear to be sound, so far, and the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights are upheld (largely).

In some ways, Paganism in South Africa is surprisingly similar to what is found in other parts of the world, which includes many of the same tensions and discussions, such as religious respect and freedom; cultural appropriation and influence; racial and ethnic disparity and inclusivity – to name a few. At the same time, this growing community was birthed within both a unique socio-cultural climate and specific a geographical environment, which informs it and allows it to thrive in its own way.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Thanks Terence. A footnote perhaps… Temple Ubuntu no longer exists, and Andi Fisher now lives in Australia. 😉

How is that relevant to the article Damon? Still Pagan, still African (by birth) and my views have not changed on African Paganism or the terminology that is so offensive to the African worldview. – Andi (Fisher) Graf

Yay, thanks. Nice to have our existence recognised.

When looking at the Title witchcraft in South Africa, I thought that this might refer to the African practices of the Sangoma in relation to the various Tribal constituents that make up Africa rather than the white perspective of ‘paganism’. The far older Pagan Rites of the Zulu, and other tribal Africans go back further than White Practices go back and could teach us a number of things that are missing in our ‘White Wiccan and Pagan Communities’, where we at best worship a God and/or Goddess, where the African people have a multiplicity of Deities representative of Rivers, Land, good magic , Bad Magic, the Sky, The Sea, Rain, Wind, The Lion, The Elephant, The Giraffe, and numerous deities that may be Human or animal inspired as well as other worldly beings from outside of our planet, that brought about such religious practices as the Ju-Ju, and Mau-Mau.

I have kept in touch with South African Pagans since 2007. Some of their problems are unique to the culture they have, as said the Black belief that Witches are always negative and that South Africa remains in its second long case of Satanic Panic where all kinds of crime and misbehavior, including teenage rebellion is blamed on Satanic infuences. Add some Christian ministers, the media and even a police united based on alleged harmful religious practices, once known as the Occult Crime Unit, and it keeps Satanic fear panic keeps being reinforced purposely.