“My world, my Earth is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and fought and gobbled until there was nothing left, and then we died. We controlled neither appetite nor violence; we did not adapt. We destroyed ourselves. But we destroyed the world first.” – Ursula K. LeGuin, The Dispossessed

A Fire in the Earth

I’m not sure what was on my mind that morning, other than hoping I could reach Columbus by nightfall, but as I drove west on I-80 through eastern Pennsylvania I started to zone out. It wasn’t until I hit Bloomsburg that I realized that I had missed the exit for I-81. I pulled off at the downtown exit with the intention of turning around, but after I got some coffee and walked around to stretch my legs a bit, I was seduced by the beautiful, sunny day and decided that, rather than head back the opposite direction on I-80, I would take the back roads southward through the country towards I-81.

I pulled out the map from under the passenger seat, which by the design and typeface looked as though it had been printed at least fifteen or twenty years earlier, and quickly found what looked like the most sensible route to take. It looked easy enough. Keep heading further down 487 towards Catawissa, where the numbered route would change to 42 and, then, continue on through Numidia and into Centralia. In Centralia, the route would then again change to 61, which would take me down through Ashland and, then, through Gordon, where I could meet up with I-81.

Route 42 over the Susquehanna River into Catawissa. [Photo by jakec, via CC lic. Wikimedia]

And yet, the town was empty. There were streets and intersections just as it showed on the map, but very few signs of civilization. Curious, I took a right turn onto what was supposed to be the main drag, and drove slowly in silent horror as the abandoned emptiness continued on and stretched all the way to the end of town. Driveway after driveway led to nothing but empty lots. Sidewalks were overgrown and obviously hadn’t been tended to in years. Mailboxes sat in front of bare foundations. The few houses that still stood literally looked terrified in the midst of their abandoned surroundings. There was not a single person in sight.

I parked the car on the side of the road and got out for a moment. There was a strange, acrid smell in the air. The silence was deafening, and yet amidst that silence I could literally hear the land screaming. The ominous feeling in my gut grew stronger by the second. I quickly became overwhelmed, got back in the car, and turned around to return back to my intended route. I looked at the map again. My faith in its accuracy was already shaken, but I needed to make sure I knew how to get out of this place. According to the map, Route 61 would take me straight out of town, and I needed to fork right just after the cemetery in order to stay on the highway.

The fork didn’t exist, however. Instead, the road forced me left, onto another road that was marked as a side-road on my map but according to the signs in front of me was now also Route 61. I glanced at the map once more, and then again at the highway in disbelief. My eyes were not playing tricks on me. The abandonment of a town, the re-alignment of a highway, something had definitely happened in this area over the years.

A few minutes down the road, I arrived at the next town, which I was relieved to find was no different than any other small Pennsylvania town, complete with buildings, people, and commerce. I parked and walked into a pizzeria and ordered a slice to go. As I was being rung up, I caught the cashier’s eye and decided to ask him about what I had just seen.

“Hey, why is the town just north of here deserted?” I asked, calmly and politely. “And is that related to why 61 is in a different place than what is marked on my map?”

He looked at me somewhat surprised, as though he couldn’t understand why anyone had to ask such a question. “You’re not from around here,” he said slowly as he handed me my change. It was a statement, not a question.

I nodded in affirmation. He continued as he started to cut my slice.

“There was a fire, its still burning. It’s a ghost town. The authorities forced just about everyone out over the past thirty years or so. There’s a few stragglers, but it’s not safe to live there and they know it. It’s dangerous to even walk around there. The ground, its hot to the touch from the fire. ”

I remembered the acrid smell in the air, but I hadn’t seen any fire. “The fire? Where’s the fire?”

“Underground,” he said, gruffly. “There’s a fire in the earth, in the mines, it started in the mines but they say it goes even deeper now. Its been burning since I was a kid. “

Smoke seeping out of the ground in Centralia, PA. [Photo by jrmski]

From the early 1800s onwards, Pennsylvania and West Virginia were at the center of the nation’s coal industry, which fueled the Industrial Age and continues to help fuel “progress” in the modern day. The first anthracite mines in Centralia opened in the 1850s, and the town became quickly populated by mine workers, who were for the most part of Irish Catholic ancestry. At its peak in 1890, nearly three thousand people lived in Centralia, and the coal deposits in the area were mined continuously until the Depression. A limited amount of mining continued through the early 1960s, right up to the time of the fire that would eventually lead to the evacuation of the entire town.

While the origin of the fire has been somewhat debated over the years, most agree that it was caused by an intentional landfill fire that was set in a former strip mine at the edge of town. The fire accidentally ignited an exposed coal shelf that extended underground to the numerous abandoned mines, some which had been dug nearly a century earlier and had long since collapsed. The fire quickly spread underground, and a few months later all of the area mines had to be permanently evacuated. It continued to spread further over the years, and by the early 1980s, residents started to experience health and other environmental effects. In 1984, Congress allocated money in order to relocate the residents of Centralia, and many residents accepted a buyout in exchange for moving to nearby towns while others stayed despite the ever-growing danger.

Nearly a decade later, thirty years after the fire started, and after four separate excavation attempts and untold millions of dollars were spent trying to put out the fire, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania decided to invoke eminent domain in order to displace the remaining residents. Aside from eight residents who fought relocation and were eventually allowed to stay until their deaths, the town has been completely abandoned. The buildings were razed, much of the infrastructure removed, and what remains is crumbling and overgrown.

Some of the trees have turned white from the fumes. The ground is so hot that in some places, a match will light if you drop it. Smoke seeps out of cracks in the earth and the smell of burning coal permeates throughout. Route 61 had to be re-routed due to cracks and fissures that appeared in the original road over time.

Overgrown and destroyed segment of Route 61 in Centralia. [Photo by navy2004.]

Experts estimate that the fire beneath Centralia, Pennsylvania will be burning for the next 250 years.

Black Gold and Bleeding Veins

In addition to coal mining, nowadays we rely mostly on conventional oil drilling, hydraulic fracking, and most recently the extraction of tar sands in order to fuel our march towards “progress”, our march towards our eventual extinction as a species. Tar sands oil has been described by climate scientist James Hansen as “one of the dirtiest, most carbon-intensive fuels on the planet,” and it is the extraction of tar sands from northern Alberta that is driving the push for environmentally devastating projects such as the Keystone XL pipeline.

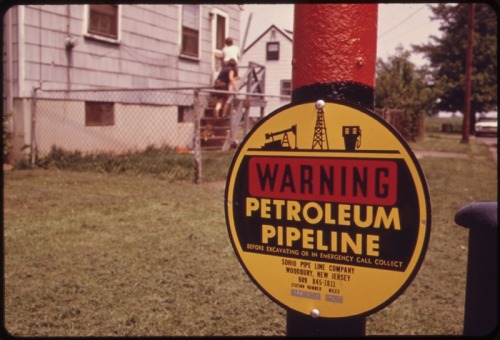

I hear lots of talk of “the pipeline” lately, as though it was a singular entity, as though there weren’t already 2.3 million miles of pipeline laid beneath American soil. It’s a positive sign overall that the average person is finally paying attention to pipelines and, while Keystone XL is undoubtedly the most widely-publicized and controversial pipeline project in American history, the focus on Keystone XL as though it is a singularity distracts from the fact that pipelines are already everywhere, wreaking environmental damage and destruction throughout the nation.

For all you know, there could be a pipeline directly underneath your own local, sacred refuge.

Millions of miles of metal veins criss-cross the country, with black gold coursing through on the journey from source to destination. Metal veins that lie under streams, across fault lines, through watersheds, beneath farmlands and cemeteries, shoddily-built metal veins that often bleed out that black gold that runs through them, seeping out through uncountable leaks and fissures, poisoning the land we live on in the name of “profits” and “freedom.” From 2008 to 2012, pipelines beneath American soil have spilled an average of more than 3.1 million gallons of toxic liquids each year, causing at least $1.5 billion in property damage. Potentially leaky pipelines are literally in our backyards.

Pipeline warning sign in a neighborhood in suburban New Jersey circa 1974. [Photo by Ike Vern.]

Earlier this year, an energy company known as Williams Partners announced its intention to place a natural gas pipeline in the ground through eastern Pennsylvania in order to cheaply move liquefied natural gas (acquired by fracking) from the Marcellus Shale across the state to the Eastern Seaboard. The pipeline, dubbed ‘Atlantic Sunrise’, would stretch through eight counties on a north-south trajectory, connecting two pre-existing pipelines that run across the northern and southern ends of the state. Local residents and Native groups have mounted a significant challenge, and some local government officials are also against the project, but the project is still under review and no decisions have been made either way.

The Atlantic Sunrise pipeline is slated to be built less than twenty miles to the west of the still-burning Centralia mine fire.

An “Act of War”

The proposed Keystone XL pipeline would be the final section of a multi-phase pipeline system that has been under construction since 2008. The first phase, completed in 2010, delivers tar sands oil from Hardisty, Alberta through Saskatchewan and the Dakotas to Steele City, Nebraska, and then on across Missouri to refineries in Illinois. The second and third phases connect to the first pipeline in Steele City and carry the oil south through Oklahoma to a refinery in Port Arthur and Houston, Texas. The Keystone XL pipeline, which still awaits government approval, would duplicate the route from Hardisty to Steele City, but would go through Montana in order to transport Bakken crude, as well as tar sands, through the Midwest.

Keystone XL is slated to cross active seismic zones, fracking wells, the Ogallala Aquifer, and numerous indigenous lands and sacred sites. Opposition to the project has been steadily increasing among the American public. However, support for the project remains strong in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Keystone XL vigil in Portland, Oregon, February 2014. [Photo by Brylie Oxley.]

On Friday, November 14th, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to authorize the Keystone XL pipeline by a 252-161 vote. In response to the vote, Rosebud Sioux Tribal President Cyril Scott stated the following: “We are outraged at the lack of intergovernmental cooperation. We are a sovereign nation and we are not being treated as such. We will close our reservation borders to Keystone XL. Authorizing Keystone XL is an act of war against our people.” Scott added that, not only does the Keystone XL pipeline violate the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, but also the Sioux Nation has not been properly consulted on the project by either the U.S. government or TransCanada, who owns the Keystone Pipeline network.

Four days after the House voted to approve Keystone XL, the proposal lost by one vote in the Senate, which is currently controlled by the Democratic Party. However, the Republican Party will gain control on January 1, and the Keystone XL proposal will undoubtedly be approved next spring. Whether or not they will have enough votes to override a presidential veto has yet to be determined. In the meantime, other pipeline proposals are in the works, and alternative plans to move crude oil are already being discussed should the Keystone XL proposal fail.

Whether its Keystone XL or the Atlantic Sunrise project, a war is indeed being waged against the land; against the gods and spirits that inhabit that land; against the health and well-being of the animals and people who inhabit that land and against all life as we know it. This war is not over a cause nor a belief, it’s a war being waged in the name of greed and profit. It is a battle for the fate of the planet itself.

Our addiction to oil and gas is literally destroying our ability to live on this planet, and yet it continues undisturbed and unfettered over the objections of many, but nowhere near enough, people. Despite the limited successes of pipeline resistance movements such as the Tar Sands Blockade and Idle No More, the extraction still increases and the poisoning of the land and its people still continues at an unprecedented rate, with no end in sight.

How much more does the Earth need to burn and bleed before we change our ways? How many more towns will we be forced to be abandoned, how many more oil trains must derail, how many more pipelines must leak before finally decide that enough is enough? How many more must die, how many more must be poisoned before we finally realize that the land that we live on is more important than profit?

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Well Alley, this post was as aptly written as it is depressing.

I am thanking you for updating us on this horrid project. In Europe no-one talks about it but I understand now how huge this is.

I hope the opposition forces will somewhat manage to derail or at least minimize this project bu looking at the new Republican majority in both chambers gives me little hope.

I heard a program about Centralia on NPR during a drive in the last month or so. I didn’t remember the state, but once you started talking about the smell and the smoke, I was pretty sure you were writing about the same town.

I participate in political action against pipelines of this scale, mostly of the written sort. It is so penny-wise/pound-foolish in many ways as to be obvious to anyone who hasn’t a financial or political stake in the matter.

Weren’t we takling about pervasive underlying racism in this country? Well, I’d heard about the aquifer (I seem to recall that once used/poisoned, the aquifer is dead and cannot be revived), but apparently not until now, that the proposed project crosses several reservations and those Native Nations’ leaders were not consulted. Typical.

I could probably write a whole second column just on the racism that is usually inherent in environmental decisions, especially pipelines and projects that use eminent domain. Its horrifying once you start to see the patterns, and most folks are quite ignorant of what goes on.

I’ll gladly read it. I live a county away from San Bruno, CA, where three? four? years ago there was a major gas pipline explosion where PG&E was found to have ignored its own review/repair policy. The CA PUC was found to be in cahoots with PG&E in several matters (as many ratepayers had suspected), and heads are rolling, and fines being levied with strong words about how much of the repairs they can foist back on the ratepayers.

I promise not to talk about how little coverage for electricity, phone, internet is found on our larger reservations, or ready availability of enough fresh water (it’s too expensive for our poor utilities)…but is starting to be funded by US concerns for other vast tracts of land on another continent. You know, that charity begins at home thing, right?

Please write that article.

Echoing the other commenters, I too would love to read that article.

One question: are the figures below correct, or does one of them need enhancing?

From 2008 to 2012, pipelines beneath American soil have spilled an average of more than **3.1 gallons of toxic liquids each year**, causing at least **$1.5 billion** in property damage.

Should have been 3.1 million. Thanks for catching that.

Wow… you really weren’t from around there 😉 I went to college about three hours north in Geneseo, NY, and learned about Centralia from Geology students who went there (or nearby) on a field trip. Its probably the most famous ghost town East of the Mississippi River.

I’m on the “second tier” from Centralia, as it were. I watched the newspaper and TV coverage of it from the southeastern corner of PA. There’s a documentary or three out there of the sort that was made about Love Canal and Three Mile Island, none of which get the airing they should get.

It’s from that perspective that I offer this opinion: it’s much more than a cautionary tale. It’s a horrific monster held at bay by those most vulnerable to being injured by it should the full truth of it become known. Its ramifications for the present are as strong as ever, and Keystone XL is merely the most high-profile of the many incipient repetitions of Centralia out there.

You can lead humans to knowledge, but you can’t make them think. Even worse, those who can think are simply more interested in profit and wealth, and damn the consequences for the rest of us. The truth of our society, Alley, says this jaded old man, is there is one coin out there with no other options. On one side people are only motivated to fight for NIMBY. On the flip-side they cannot be motivated to care about anyone else’s back yard.

My youngest is making much noise in Chicago over social issues. I hope you can allow me some benign ageism in expressing that my pride in her commitment to her conscience is equally aimed to you, whom I’d be proud to call “daughter” as well.

Be well, be well, in all things be well.

Talk of Centralia without a single mention of the film adaptation of the computer game “Silent Hill”?

I’m impressed.

I guess it proves Alley’s actually serious about what she does…But indeed, I think most people (me included) got a flash reading this post.

I didn’t even know about Silent Hill until I went looking for specifics on Centralia the other day. I’m one of those weirdos who doesn’t watch TV or play computer games and is rather ignorant of pop culture. But now, of course, I want to see the movie 🙂

It’s actually a really interesting movie. I’ve not played the games, so I don’t know how well it does against them, but it certainly was enjoyable for me.

(Mind you, Pinhead is one of my cinematic heroes…)

Movie’s good indeed: Creep factor’s very high at the beginning.

Great article as usual, Alley.

The phrase you used about hearing the earth screaming struck me. I hear that cry so often. As Pagans, Earth-based religionists, ecospiritual people, etc, how do we continue to relate to the Earth in a way that hears and understands that scream? How do people claim to be in relation with the Earth and be rooted in place without hearing that scream? And once you hear it, how can you ignore it?

Within our movement we have the ability to make a difference. It will take people who are intimately, spiritually connected with the planet to wake people up. I fear it is too late, but if we are to do anything its time to drop our awareness back into our hearts, our bodies, and the Earth.

Thank you for all you do.

Unfortunately, this will not stop until the people do something about it. People, nature, wildlife, etc is extremely unimportant to the wealthy.

I think our next Presidents going to be another Oil Man. Good news for me, and I guess bad news for the rest of you. And remember your living in the best of all possible worlds!

I’ve been near there quite a few times. It is sad how that town went from a small bustling town to nothing. There was talk of removing any signs of Centralia for good, but when I am out that way, the signs remain. Its a shame that Centralia cannot come back.

I watched the story develop over the decades. I knew actually what the article was about the moment the name was said. By the way chia has thousands of coal mine fires going on. Again there is no way to stop it. Fracking ad oil drilling require so much and poison so much ground water that it is beyond belief that we are still doing it just to get rid of our remaining oil and natural gas deposits as fast as possible. We are doing this in areas that already are running out of group water resources for people and farming.

The answer to the question is simple. Never.