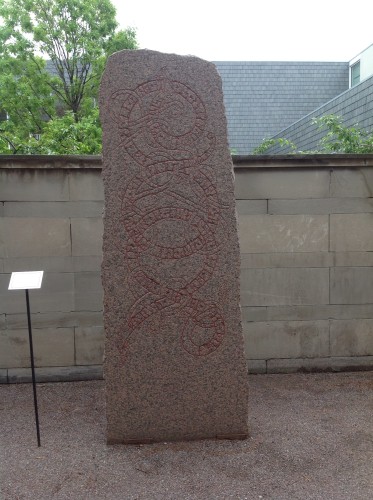

The Minneapolis Runestone. Located outside the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, it was a gift from the City of Uppsala. Photo by your devoted author.

The page looks like something out of The Shining: line after line of the same eight words repeating endlessly, with errors as the only variation. Hestur. Hest. Hesti. Hests. That’s the singular. Hestar. Hesta. Hestum. Hesta. That’s the plural. This is the paradigm for Icelandic masculine singular indefinite nouns. If we add the definite article, we get hesturinn, hestinn, hestinum, hestsins, hestarnir, hestana, hestunum, hestanna. Sixteen ways to say “horse.”

I am on my third consecutive page of inscribing hestur, the first of six major noun paradigms, into a yellow single-subject notebook, hoping that by the sheer force of repetition I will work these forms into memory. There may be some other way of doing this that doesn’t kill so many trees, but I haven’t found it. The only way I know how to memorize these words is to carve their names into the pulped flesh of trees, like runes, hoping their magical formula will unfold onto me given enough diligence.

This is my third week of an intensive summer course in the modern Icelandic language that I am taking at the University of Minnesota. I spent the last three weeks in Minneapolis, but the class will be flying to Reykjavik on Friday evening, just a few hours after this is published. We will spend another three weeks in Iceland practicing the language in its natural context among native speakers. I can’t help but be nervous – I never studied abroad in college, could never afford it. My feet have never left North American soil for more than five days at a time before. The prospect of learning to operate in this new language, even for just a few weeks, is intimidating; I haven’t studied a living language in almost a decade, not since I took my last semester of French in 2004 and promptly forgot everything about it. I’ve stuck to dead languages since then, Old English and Old Norse, tongues whose precise intonations are unknown and largely unimportant. I haven’t spoken a language besides English on a regular basis since I was 18 years old.

Mynd now – “picture,” the paradigm for the strong feminine nouns. With the definite article, that’s myndin, myndina, myndinni, myndarinnar…

As I lay out the paradigms in their places on the grid of lined paper, I find myself thinking back to a conversation I had with my friend Christian a few months ago. We were at a meeting for Hearthfires, the local Pagan meetup group back home in Columbia, and we were talking about languages; I believe I had just sent in my application for the Icelandic course, which may have been the genesis of the conversation. Christian, who is a Romano-Celtic polytheist, mentioned that he wished he knew Latin better. “My prayers would be better received in Latin,” he said. That sentence has stuck with me for the past few months. I suspect it’s because I can’t decide whether or not I agree with him.

The idea – as I understand it, anyway – behind the sentiment is that, since Christian’s gods were historically worshipped by speakers of Latin, Latin is the natural language with which to address those deities. I know many reconstructionist Pagans feel the same way; not long ago, I helped my family friend Alaric Albertsson – whom I still instinctively refer to as “Uncle Alaric” – proofread some sentences in Old English that an acquaintance of his was producing for his ADF training. Since they are Anglo-Saxon Heathens, Old English is the language they feel is most appropriate for their rituals.

Now, it doesn’t matter to me how any individual performs their rituals – there is something beautiful in giving new voice to a dead language in such a context, and in any case, everyone has the right to practice their religion in the way that makes the most sense to them. But I do have problems with the line of thinking that suggests the old languages are the “correct” languages with which to address the gods; to me, that romanticizes the past and discounts the legitimacy of present-day worship. After all, referring to my own Heathen inclinations, the Icelanders spoke of their gods in the same language they used for courtship, commerce, and craftwork. They didn’t restrict themselves to Proto-Germanic (or, gods help us, Proto-Indo-European), even though those were the languages in use when the Norse gods came into knowledge. The medieval Icelanders addressed Thor in their native tongue – why would it be any different for me to address him in mine?

Of course, I write this while in the middle of a difficult language course that I am taking only because of my religious yearning. Icelandic is not a very practical foreign language to study; its grammar is dense and finicky, its community of native speakers is quite small, and most Icelanders have an excellent grasp of English. Icelandic has some practical uses for me, of course – last fall, I came across an article that looked like a brilliant resource for a seminar paper I was writing, but, because it was in Icelandic, I couldn’t read it. But those are, if I am honest, secondary concerns. I am learning Icelandic because the language appeals to me as a Heathen; I am studying it, whether I want to admit it or not, because I feel like it will lead to my prayers being better received.

Borð, now. “Table.” Strong neuter paradigm. Same form in the singular and plural…

I am aware that modern Icelandic is hardly the language of the Aesir; for the past thousand years, its speakers have been overwhelmingly Christian. Even Old Norse, which Icelandic still closely resembles, was the tongue of a long-converted nation by the time the golden age of medieval Icelandic literature came about. And there’s hardly anything religious about learning how to say, “On Saturday, I will wake up at nine o’clock.” (“Á laugurdaginn ætla ég að vakna um klukkan níu,” if you were wondering – or at least that’s what my notes say.) I can’t say, really, why this language has a hold on me, any more than I can say why I have dreamed of visiting Iceland itself for years. Unlike some of my classmates, I have no Icelandic grandparents or distant cousins waiting for me in Reykjavik; I have been possessed by a nostalgia for a place my ancestors have never walked, a longing for a language nobody in my family has ever spoken.

I don’t know why these things have such a hold on me, but they do. In less than 24 hours, I will be taking my first steps into Iceland, breathing in my first breath of Reykjavik air. I will be hungry and bone-tired after the red-eye flight from Minneapolis. What will I feel in that moment?

I don’t know, but I am about to find out.

Valhalla, ég er koma. Valhalla, I am coming.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

While I’ve always thought that gods were smart enough to figure out languages as time passes, there’s something to be said for how language shapes culture. Many of my more traditional Lakota relatives tell me that to understand a language is to understand a culture, and that viewpoint is necessary for interacting with the spirits and gods of that culture.

I think there’s something to be said for both approaches….

Except you can learn about Lakota, Tamil, and Yaqui people’s from those people’s, and you can observe how the language colors their everyday lives. For the rest of these people, their language and beliefs went to the wayside long ago. Sure there are folk survivals, but the languages have changed and the cultures have changed. The unique combination in which these religions arose are gone and the opportunity to study them in depth and really *understand* the culture is also gone.

We can make assumptions, but we may be off point in our interpretations even when we can examine a *living culture*. Horace Miner pretty well demonstrates this in his essay “Body Ritual Among the Nacriema”. I can see the logic of it being necessary to learn a language when engaging in a religion which was not stamped out 1600 years ago, yet when I think about it I don’t necessarily know that learning a long dead vernacular is going to help me engage with my gods any better than addressing them in my mother tongue.

Of course, that being said, I’m still trying to learn ancient Greek so clearly I don’t think learning the source language is *completely* pointless, I just don’t think it is a necessity.

I am of that viewpoint as well. I remember the lightbulb that went off in my college Field Linguistics class. Our “informant” was from Peru. Her first language was Quechua, second Spanish, and third, English.

One day we were talking about past and future. For the Inca, the past is the direction one faces, whereas the future is behind us–when she used the non-verbal wave of hand, suddenly we realized that they think of time differently from most of Western culture.

I tend to advocate learning additional languages for several reasons, some of them being the broadening of the cultural mindset, the ability to communicate with strangers or “Old Country” family, and because many US folk don’t see why they should learn another language, even when they travel abroad. Most Europeans speak at least three, many indigenous folks all over the world at least two.

I admit freely that I have a gift and a lifelong interest in language and languages. I like being able to identify accents, people’s ethnicity by their names or accent, and to be able to say at least: hello, goodbye, thank you, and one or two more phrases. You should see how people’s eyes light up when you address them in their language or identify where they’re from.

Forgot this. One would hope our deities can understand current languages, given that they’ve been around during their development. While they may appreciate hearing the old words, I certainly expect them to understand each one’s own common speech. If not, are they truly gods?

Depends on how you define a god.

I am not entirely sure that god and other Ƿihta actually understand human speech at all.

Tell me more! If they do not understand human speech at all, of what nature is the communication between them and humans? This is all relatively new territory for me, that idea…

What is the nature of communication?

I am English, it is my only language (we shall ignore the bit of French and German that I learned at school, or the piecemeal words I have in a scattering of other languages). In English we have a funny little four letter word that is used to describe a hugely important conceptual emotion – “Love”.

Does the word do the emotion justice? I would say not. It is even more reductionist than Greek, with its words for various types of love (from eros to philia).

Imagine if you could communicate *directly* how you feel to others, without the clumsy use of verbal language.

Why would the Ƿihta not be able to communicate in such a way? If nothing else, it makes a lot more sense. Human language is the result of human physiology, but the Ƿihta

have no such physical limitation, do they?

This goes into what the nature of the Ƿihta are, which is obviously contentious ground but, since I am a hard polytheist/Ēalgodan, I believe that they exist as non-physical organisms and, as such, are not constrained by human modes of communication.

Words are useful, for humans, but it is the sentiment that those words carry that are of importance.

How many times have I wished I could find a better word for something hard to describe? Immediately grokked, thank you.

Not a problem. Although, the irony of using human language to communicate the limitations of human language is not lost on me.

“God is an iron.” — Spider Robinson

Unless trees grow horizontally in Minneapolis, the graphic is rotated 90 degrees.

The perils of composing on an iPad. Sorry, will fix.

Photo has been fixed.

All praise to the editor!

In Cultus Deorum Romanum, Latin is the preferred ecclesiastical and religious language because of the exacting formulaic nature of the Roman religion. It fits better in form and function than, say, English specifically because of how formulaic the religion is, with very precise methodological rituals. Likewise, I’m of the same mind of Englatheod that Old English is an appropriate liturgical language for any Anglo-Saxon heathen rituals as opposed to Nīwenglisce. To me, learning the original language(s) is part of my academic training, but it also gives me a more in-depth understanding to the culture, like others have said. It also allows you to read original source material without needing translation, which prevents yet another bias from creeping into the context. And I am very bad at languages.

I think people want something…unique or mysterious to their rituals and traditions, so they reach back towards other languages that less people may know. But we should remember that even the Catholic Church realized it was losing a battle when it didn’t have Mass in the vernacular, and changed to accommodate that. So I guess I’ll just repeat what other people will say: Whatever works, works.

I certainly love to study old languages – I’ve spent a considerable chunk of my life on Old English in particular. Reading the sources in the original language is important academically for exactly the reasons you describe – and also because there is a literally magical component to hearing your voice in these tongues from other times. My worry is just that if we overemphasize that, though, it makes our own practice seem lesser by comparison.

In my college days (many, many thousands of moons ago 😀 ) I was privileged to learn to read aloud Beowulf, high Middle English to early modern English (what’s widely and not altogether accurately labeled the morality plays*) and Shakespeare’s English as She Was Actually Spoken. 😀

I experienced that magic, intensely and viscerally. I nearly peed myself twice while reading Beowabbit, for its spot-on parody of Beowulf. The educational and entertainment benefits from those classes remains endless. 🙂

* My favorite was (some alternate titles out there) “Johan Johan, Tyb His Wife, and Sir Johan the Priest.” There is a magic and musical quality to the writing and dialogue in the original that invariably gets lost in moderninizing or translating. Some day I’ll re-immerse myself in it, at least by producing that play for the Philly Fringe Festival.

I, too, am bothered by the notion that “prayers are better received” in languages of the past, though I understand the yearning well enough to have felt quite a spurt of jealousy when I read of your traveling to Iceland to practice this new skill…

I don’t know that our prayers are heard better in older tongues, but I am quite sure that there is something significant about actually mastering the skills and crafts that were at the heart of the cultures in which our gods arose. A Wiccan who invokes the element of Fire, but has never split their own wood or tended a wood stove on a cold winter night simply does not have as deep an understanding of Fire as one who has done so. Someone who is cultivating a spiritual relationship with wolves, but has never observed, let alone studied, actual wolves will have a weaker, thinner understanding of what a wolf is.

Many years ago, I had an experience with a goddess who spins, who put a thread into my hand. I can take a hint: I took up spinning. Like many people who take up a new craft, I spent an enormous number of hours practicing it. And though I would never pretend I am a master of that craft, I have gained enough skill that I spin the yarn with which I knit my sweaters, socks, and shawls.

More to the point, as my hands learned the skill of spinning wool, I began to dream of spinning. I had intense, sensual dreams of energy as well as fiber spiraling, spiraling, spiraling out from the palms of my hands–approximately where I feel the draft when I use a long-draw on my drop spindle. I dreamed about spinning wool for figures in ancient history, and while I’ll spare you the details, I’m convinced that having learned to spin, I also learned to connect to that goddess in a far deeper, truer way. I saw and felt things about spinning I never could have done from watching others do it.

I suspect languages are the same. Perhaps any ancient skill connected to our gods has some of these elements: using a sword, learning to forge a nail, throw a pot… even bake a loaf of bread.

Of course the gods have modern skills and associations,too. But I bet we’ll learn them best, with the least intellectual projection of our wishes and fancies, if we take in a few of the old skills first.

Of course, spinning may be both spinning and more than spinning. The symbolic connections between spinning and fate are well established across several cultures. No reason the art of spinning wouldn’t have lessons to teach there, as well.

Prayers are not better received in the languages of the past, but there is still great value in studying the elder tongues. As Kadiera has also noted , language shapes culture. We study the elder tongues, whether Icelandic, Old English, Latin, Old Irish or, in my case Gaulish, not so the Gods will understand us but rather so we can better understand, appreciate, and, when appropriate, emulate ancient thought processes. Even when no modern continuity exists, the vocabulary and grammar of the ancient tongues can teach us very much, especially when we flesh it out with the ancient literature, when we have it, or inscriptions.

I’m not going to say whether it is a necessity. It depends on what one means by a necessity, I suppose. But it is a pursuit of great value, and I can say from experience that my life is richer for it.

You say that with remarkable certitude. Have the Gods told you personally that they don’t prefer the elder tongues?

“After all, referring to my own Heathen inclinations, the Icelanders spoke of their gods in the same language they used for courtship, commerce, and craftwork.”

While this is true, it is equally true that they did so in a different (one might say “higher”) register of that same language, one that was quite a bit more archaic and obscure. In a word, the gods were worshiped with poetry, and old poetic traditions have a strong tendency to preserve archaic words, usages, inflections and declensions, as well as to intentionally strive for riddle-like speech. Read a kenning-heavy piece of scaldic verse, for instance, and remember the line from the Rig Veda: “The gods love the obscure.”

From your experience of Anglo-Saxon, I could mention the reduplicating preterit forms of class 7 strong verbs that show up only in poetry, having long been replaced by other forms in ordinary prose Anglo-Saxon.

I might also recommend Calvert Watkins’ excellent “How to Kill a Dragon” for an in-depth look at the vital importance of poetry in different Indo-European cultures (including Germanic), especially if followed by M.L. West’s “Indo-European Poetry and Myth”. The upshot, for this conversation, is that poetry was intimately linked with ritual, that poetic registers in Indo-European languages are very conservative and preserving of archaisms at the same time that they encourage the production of new poems, and that the poetic registers in these languages show clear signs of descending ultimately from a common poetic tradition.

Theodish Belief has long used early Germanic languages in a liturgical context, both poetry from the early sources and recent poetry composed in the old languages. I have composed new poems and memorized old poems for liturgical purposes. We have also had to field questions similar to those posed here, about the appropriateness of using old vs. new languages for these purposes, given that the gods surely understand the languages we speak now.

Many answers are possible, and I tend to think along these lines: the old poetry that I’ve had to translate and memorize is, in my opinion, better than just about anything that I’ve read in modern English in terms of its evocative imagery and densely-packed meanings. It is very good poetry, and I see no reason not to use it in the worship of the gods. This is also a good reason, I think, for composing new poetry in that old poetic tradition (seeing as that tradition has explicit links with the worship of the gods I worship). Also, modern English is much more difficult to fit into that old verse form; not impossible, and Tolkien was probably one of the best, but it still seems kind of forced and artificial. I have thoughts on how to compose liturgical poetry in modern English in a style that would be a continuation and development of the old style, but I would like to save that for a different conversation.

Also, even though we use ancient languages in our rituals, I have never heard anyone say that we must do so exclusively. I tend to prefer ancient languages, but I also use modern English and German in ritual contexts (again, poetry, and also song). I do not think that a binary opposition exists.

Whether this is what you implied, or what tangent my brain took (does that often, it does), I think that speaking or otherwise using the/a language used by those who forged the path that one chooses (or is chosen) to follow, can be seen as a ritual tool. We don’t always have to use that tool, and there are lots of ritual tools that one might not use at all.

That being said, am I likely to learn one of the ancient Greek languages/dialects, Old Irish, Egyptian as spoken at the time Anubis was worshipped, or what was spoken in Crete at the time of the Minotaur?

Would I be able to find teachers for the last two at all?

One could see using an old language as a ritual tool, to be used or or left in one’s “ritual toolbox”, so to speak. I think it depends on one’s ritual practice and tradition. For me, it’s more than that.

I (like yourself, judging from your other responses here) have a love of languages and a deep respect for them: besides English and German, I have a working understanding of Old English, Old Saxon, Old Icelandic and Old Frisian, have studied Latin, Sanskrit, and French, and did a little bit of linguistic field study with Lakota; I would also dearly love to learn Finnish, Japanese, and Mandarin before I die. I spent half an hour this morning geeking out over the agglutinative structure of a word in Quechua meaning “they were only teaching each other (yači-či-na-ku-tla-sa-rqa-nku)”.

Kadiera says above: “Many of my more traditional Lakota relatives tell me that to understand a language is to understand a culture, and that viewpoint is necessary for interacting with the spirits and gods of that culture.”

I hold that point of view myself. The particular reconstructionist approach of my tradition is not merely the adoption of Germanic religion, but the adoption of the Germanic “mental culture” that is the religion’s proper environment, and without which, it is difficult to actually understand the religion. This comes down to understanding the religion, gods, and wights on their own terms, which is what Kadiera’s more traditional Lakota relatives seem to be getting at.

Ancient Greek and Old Irish are certainly very learnable; both have several guides and existing literature (including, to get back to my major point above, extant *poetic traditions* including religious poetry). Egyptian is learnable, too (and the literature also includes poetry), although the nature of the writing system means that the pronunciation and placement of vowels in words is largely unknown; KhonsuMes Matt mentions something below about phonetic reconstruction, so he would probably be a good resource for that sort of thing. I have a feeling that, with enough familiarity with Egyptian, with Coptic, and with related languages in that family, one might be able to get close.

With Minoan, unfortunately, I think you’re out of luck until there is a breakthrough deciphering Cretan hieroglyphs and/or Linear A. As of yet, Minoan is undecipherable.

Having spent a year in Iceland learning Medieval Icelandic, I understand the pain. This language is really really hard, and that’s coming from a European who spoke three languages before attempting this one !

Also coming from a country where being bi lingual is a charming oddity, I also understand the feeling of having to work extra hard in order to get a second language, but god Iceland is probably the most complicated European language after the likes of Finnish and co…

To come to learning the language, I can say that it took me a full semester (3,5 months) before feeling somewhat confident in reading Medieval Icelandic, but it took me a couple months more in order to be able to read the language somewhat proficiently (still,a dictionary is always useful).

There’s only one way to try to work out such a language to the point you can actually speak it: You must need it. That’s as simple as that. leaving in a country or having a relative/life partner is probably the most powerful motivation. religious devotion might rank high as well considering that I only went to learn the language in order to be able to read the Edda in the original editions. I have no idea how you will fare but if you really really are strongly minded and devoted you might gain some momentum slowly, still, i myself had to my disposal one of the top Icelandic scholars in the world and it still took time.

My advice is: once you’re finished, don’t fucking stop. If you stop actively working on the language, you’re done for. I myself after leaving Iceland teamed up with another Scandinavian study guy and now we’re having fun translating Egils saga from some battered Old Icelandic Edition. It is surprisingly easy and more than half of the text is easily understandable without thinking. Considering I barely had started the Icelandic online course a year ago i feel quite happy about it.

I hope this will go well for you too. If you have any questions, just contact me, i might be able to speak further and maybe help, who knows?

Best of luck.

P.S: better not use the term Old Norse. It’s quite an empty shell, especially when 99 per cent of the case it refers to actual Medieval Icelandic.

Personal anecdote: My mother grew up in the cosmopolitan multi-lingualism of the very end of the Austro-Hungarian period. She had English in school but had no opportunity to become conversant (let alone fluent) until she arrived in the US (1948). Her (famous amongst family and friends) method of learning to be conversant was to sit down every day with the NY Times crossword puzzle and a dictionary. She delighted in creating words and using them in conversation, words that sounded eminently plausible, conveyed her intended thought, and appeared in no dictionary ever published. She was a terror with Scrabble… but she mastered the language in which she wanted her children to be fluent and to speak without any foreign accent, and we all thank her for that (while bemoaning our ignorance of her native languages, except for some very juicy curses).

My mother was the youngest of four daughters born to Lebanese immigrants. The eldest daughter had a good grounding in that dialect of Arabic, and each sister less so, until my mother, when her mother was already sick with TB. No one had the time to teach my mother, and the one word she did repeat got her mouth washed out with soap. Given who she likely learned it from, it always seemed hypcritical of my grandfather to have done that.

She took French in high school, but didn’t keep up with it. For me, in my childhood, it was linked to ballet, which I adored. I took it in HS myself, for 4 years, French lit and Old French in college. I also took Latin (I was Catholic in the pre-Vatican II days, and had memorized some passages in the missal), and Spanish at uni–but I’d also had a summerschool class after 5th? grade, earlier.

Languages I’d like to learn are Navajo, Breton, and Basque, the last of which may be easily as difficult as Old Icelandic.

I love stories like these. Like you, I delight in listening to the nuances of language, especially spoken (recent grief: with permanent hearing loss in one ear, my discernment has gone the way of my stereo hearing 🙁 ). My father was a natural polyglot, I inherited the “connection” to other languages but not the ease with which he learned them. My daughters have that discernment, and we enjoy sharing our observations.

French was my foreign language choice in junior and high school. My favorite teacher was a Lebanese woman raised in a French Catholic orphanage, who believed living the language was at least as important as the grammar and syntax. To this day I’m sure that a week or two of immersion will restore me to conversant, and I wouldn’t hesitate to reside in a French speaking place, a gift from that teacher.

My favorite language teacher in high school, was someone who lived the language. She married a Mexican, and when that didn’t work out, came back to her home with her kids, and taught it. We learned Spanish in high school, but she also told us, that Spanish was Castillian. That is not what the natives spoke. Thus was my first introduction to cultural communication.

So what she did do, is after we learned the basics, was show us how different Hispanic countries spoke. We learned the fast Spanish of a country close to Brazil in South America, to the Puerto Rican Spanish, to the Mexican Spanish. The fast Spanish was very difficult for me to pick up.

Living the language is more important than Grammar IMO. I learned Swedish because my fiancee is a native speaker. We used to speak in English but one day I said: “From now on we speak Swedish”. I hated myself for a couple weeks afterwards as I stuttered like a toddler but it was ultimately extremely rewarding.

I lived in the campus language dorm for three years (it was also a very nice building). At lunch, you spoke the language designated at the table. Most of the Resident Assistants (aka RA’s) were married, Those with, or planning for, kids chose to have one parent speak only their preferred non-English language to the offspring, and one parent would speak another, and I forget when English would be used–likely outside the house.

I wish I’d been born to a family like that. I wish CA (at least then) hadn’t had the idiocy to keep you from learning another language before your best chance to do so was past. Should have had at least Spanish from elementary school, and not just for the gifted kids. Waiting until 8th grade is beyond useless and stupid, for most learners.

Again, learning a language a school is rarely immersing…I had seven years of German at school and i can only master two sentences, despite the fact that all of my mom’s family are native German speakers! That was quite a pity but again, I should not have expected much more from school. Language teaching should be entirely rethought so that it can actually lead children to actually learn a language.

It may not take even that long! When I was in Britanny, I did my best to stick to French. I think the first night I was there, near Locmariaquer, I think, there was a pizza place down the road from the small hotel I’d chosen. I’m afraid I was only drawn by the name: (St.?) Marina’s pizza. Now how am I supposed to ignore that, eh?

I had a book with me, but there was a loud group from West Los Angeles, speaking only in English, making it difficult for me to stay focused in a francophone mindset. They were talking about things in the WLA area, so I assumed that’s where they were from. I was living at the eastern edge of the county at the time, in Claremont.

Learning an archaic/extinct language is an interesting idea.

The motivation is the obvious key. If there are relevant texts existing in that language that you feel a need/desire to read, then it makes all kinds of sense to study the language. Otherwise you rely on the translations (and interpretations) of others.

If you feel that your liturgy requires that language, asking yourself why is pretty important. Simply by using a language that is otherwise extinct, you apply an element of elitism to your practice. What of those who do not have the ability or will to learn? Are they excluded from your religious denomination, as they cannot understand what is being said?

I want to learn Ænglisc (I am finding it a slow process) purely so that I can read Bēoƿulf in the original language it was recorded in. I am a big fan of the tale, and have several editions on the bookshelf.

I also find that it is useful as a source of loanwords for my practice. Whereas someone may have an altar or a temple, I want a hearg or a hof.

In short, whilst I would not advocate a full archaic liturgy, I would suggest becoming familiar with any relevant languages to your practice to better understand certain key concepts.

At risk of stating the obvious, it seems the importance of addressing the gods in their “native tongue” would depend on what kind of polytheist you are. A hard polytheist would probably say definitely, as they thrived in a particular time, culture, and environment; a soft polytheist would be more willing to give themselves a pass, as the deity is just another manifestation of a certain type of energy which can be felt across borders, both cultural and geographical, and can be expressed/communicated with in virtually any language. A Jungian type polytheist might say that it IS more valuable to learn the language, as that certainly triggers some response in your subconscious, which of course is the seat of the divine – or at the very least, the seat of our access to communication with the divine.

Flipping now to personal experience – I also learned a very hard language, Hungarian. (Echoing what has already been said, the very best way to learn a language is to live there and use it every day, and that’s what I did. And to keep in practice so I wouldn’t lose it, I married a Hungarian.) But all this rhetoric about language shaping culture, or even defining culture, or needing to know a language to really understand its culture – I am not so sure about that. Sure, it opens a lot of doors – you’re no longer “just a tourist” if you can speak the language, you learn a lot more about people. But if you imagined that words were completely neutral (like everyone spoke telepathically, or everyone had the same native language regardless of culture) – I don’t think in the end it would matter which language these cultural insights were given in. (It’s the content of the cultural communication that matters.)

Another example: Hungarian is a completely gender neutral language. No nouns have genders, and even he/she and his/her are the same whether you’re speaking about a male or a female. But does that magically mean that women are treated equally and there is no sexism? Of course not! Many professions, for example, get “woman” added onto the end (as in English, policewoman) but to an even stronger degree; hence we have teacherwoman, doctorwoman, etc. Gender, even in a gender-neutral language, is still important. So the fact that this language has no gender does not necessarily inform my beliefs about its culture.

As others have said, learn the language/s anyway. There is nothing like being able to read a good primary source, make new friends, have confidence in face of a strange menu, and keep your brain’s plasticity high, warding off dementia and Alzheimer’s. Cheers!

PS Had I known you were in Minneapolis, I would have invited you out for a drink! Maybe next time. 🙂

I think it’s a bit of a stretch to suggest that language encapsulating a different way of viewing the world should translate into a lack of grammatical gender (which is a defining feature of all Uralic languages btw) being a sign that there should be gender equality in a culture. In my experience, the idea is not necessarily that language defines culture, it’s that language itself is a part of the expression of that culture. It’s also not as easy to see if you are going between two related languages (either linguistically, culturally, or geographically related), as when you go to a vastly different language. What brought the truth of this home for me was studying Japanese in high school and college. Speaking a language that different really does require having to understand the world in a different way, even to think differently that you would as an English speaker.

Of course the real translation is:

“Dear Uncle Einar, We have not been this lost since we went off to raid Constantinople and ended up in Japan. And to make matters worse, Bjorn is starting to make lutefisk. We are all trying to stay upwind and figure out how to get out of this Odinnforsaken wilderness before that madman poisons us all.

Love and kisses to Aunt Helga and the rest of the family.

Eric”

Laughed so hard I scared the dog and woke the husband–from the other end of the house.

Ooops. premature post..

“I personally dislike the egyptological artificial pronunciations we are more or less forced to use. So I’m committed to working on the phonetic reconstruction aspect of the language as much as possible.”

That sounds absolutely fascinating! What sources are you using to try and reconstruct the phonetics of Egyptian?

The work of James Allen, Antonio Loprieno, Carsten Peust, James Ray, Wolfgang Schenkel primarily, so far. There will be more when I can get my hands on further references.. To get an initial picture, James Allen’s “The Ancient Egyptian Language”, 2013 is a good place to look. It is a linguistic history of Egyptian and covers much more than phonology, but the bibliography and notes lead to other sources. The journal Lingua Aegyptia is an excellent source, since it concentrates specifically on the linguistics of Egyptian across all periods. As always with Egyptology, a lot of the scholarship is in German or French, though it seems the preponderance of work in phonology is German and English. Oh, I should mention that some background in another Afro-asiatic language is very helpful. Arabic phonology has a number of commonalities with earlier Egyptian (`ayin, hamza, ‘dotted h’, and others), and some shared roots. Amharic or Hebrew would also be helpful, though modern Hebrew has lost some of the older Afro-asiatic phoneme distinctions, as has Coptic Egyptian itself.

I hope you will make a presentation at PantheaCon about this. I would *love* to hear more.

Thank you for suggesting that Marina! Perhaps when I am a bit further along. I am trying to develop a methodology that is rooted in the scholarship and transparent enough so that reconstructions can change as we learn more. I don’t want it to be a one-time kind of thing, but something that can grow and evolve over time. (Kind of like languages and dialects always do!)

You could make it a continuing series….

“Do not change the barbaric names.”

I appreciate this discussion and the fraught nature of your own inclinations on this matter, Eric.

I did my Ph.D. in Celtic to get closer to my gods and heroes; and, I do think it has helped, but more in terms of learning their culture in a deep way rather than their language (though I do use Old Irish in some things). Likewise, with Antinous, I used a lot of Latin initially, since I knew it already when I got involved with him, but also used English. However, in the last several years, I’ve also been using Greek: even though Latin was the official language of people like Hadrian, the majority of the things on Antinous are in Greek, and that is the language he would have spoken with Hadrian in private (and probably in public a lot as well). Since using Greek, my practices are that much more effective and intense, as you might have seen first-hand at PantheaCon in ’13, at very least…

I think learning a bit of one of these languages, in addition to having all of the benefits of cultural understanding, is kind of a “half-way” gesture, so to speak: even if one doesn’t offer half of one’s prayers in another language, nonetheless, using at least a few words in these languages is like saying to the deities and other divine beings “I am doing this to show you how serious I am about understanding you,” which I think then gets their attention to the extent that they know what it represents to have made such an effort. If you just start speaking in your own language to them, and–worse yet–start making demands of them on the first contact, it’s kind of like getting a spam scam e-mail demanding that one send money, but in some other language, and then being miffed because it wasn’t answered. (That may be a bad metaphor, but just think about it: we file those into our junk folders immediately and delete them…what would the gods do?)

My favorite prof & thesis advisor in college had spent time in Iceland doing research for her PhD., I think (rather than earlier degrees). This might be a publication of the thesis:

A Case Grammar Of Verbal Predicators In Old Icelandic by Karen C Kossuth. It was published in 1980, and I’m fairly certain she’d had her doctorate by 1974, but I could be wrong.

So, I’m fascinated by your working to learn the language, and envious of your chance to travel there. I, too, could not afford even a Study Abroad semester when I was in college.

You say about Icelandic–“I have no Icelandic grandparents or distant cousins waiting for me in Reykjavik; I have been possessed by a nostalgia for a place my ancestors have never walked, a longing for a language nobody in my family has ever spoken.”

I understand completely. While I like some Middle-eastern music, it has no call on me the way music from any of the Celtic cultures have on me. Why does Britanny call to me so much? Why did Scotland feel like primal home to me? In this body, I have no ancestors from those places. I had hoped the French Canadian branch had come from Britanny, but no such luck: Normandy is the departure point. There might, on my mother’s side, be a Basque woman who married into a Lebanese family, but that’s just a guess based on a blood factor that is very common among the Basque. Another lifetime? Dunno. Didn’t get enough time in Scotland or in Britanny to research anything, and I’ve never been to Basque country.

The way you are trying to learn language is the way that most educated folks try, but it doesn’t work very well. Look up Comprehensible Input, and watch this TEDx which demonstrates how to do it. BTW, I teach Latin this way, and all kinds of learners make progress. I have virtually eliminated the experience any student failing Latin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d0yGdNEWdn0