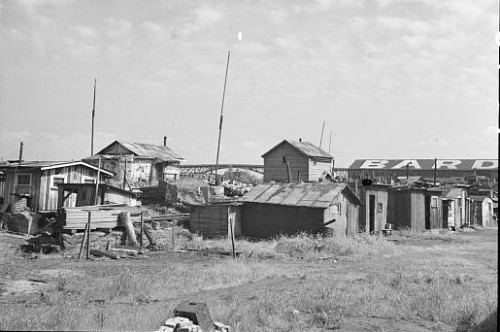

Throughout the 1930’s, Hoovervilles dotted the landscape of the Willamette Valley, just as they did throughout most of this country. The Great Depression sparked a wave of homelessness throughout the United States, a wave that triggered mass migrations and the proliferation of shantytowns that popped up everywhere from Central Park in New York City to a nine-acre settlement in Seattle on the mudflats of Puget Sound. Hoovervilles were generally tolerated throughout the Depression until the advent of WWII, when an economic resurgence triggered the eradication of the shantytowns. With the demise of the Hoovervilles, homelessness left the public spotlight but it never truly went away, hovering out of sight until the recession of the 1980’s fueled a resurgence of the visibly homeless across America.

Depression-era Hooverville just outside of Portland, Oregon

The historic parallels between the Great Depression and the Great Recession are rather illuminating in terms of understanding the patterns, attitudes, and social tendencies that are at the foundation of modern homelessness. In viewing and analyzing present-day homelessness through the lens of the Depression, notable patterns emerge as do notable differences. The stereotypes and xenophobic attitudes aimed towards poor “migrants” in the 1930’s remains mostly unchanged to this day, especially in the current attitudes of many in urban areas who are irrationally concerned about homeless migration to their towns and cities. But while the New Deal and WWII lifted many of the Depression-era poor out of their current situation, current economic and policy trends almost guarantee that poverty and homelessness in America will continue to grow. And while the Hooverville phenomenon was accepted during the Depression years out of necessity, modern-day homeless camping is not met with anywhere near the kind of understanding and tolerance that was demonstrated by municipalities in the 1930’s. Nowadays, homeless camps are seldom tolerated by either citizens or government, and often meet a cruel fate via a bulldozer and/or police vehicles. Those who were dubbed “migrants” eighty years ago are more accurately described as “refugees” in the present. They are not allowed to have their Hoovervilles. They are a people with no place to call their own.

I have spent a lot of time between these two worlds of past and present, gathering information from one in order to better understand, define, and explain the other. These connections are crucial as a basis for functioning within my primary role, one that is defined by most as “activist” but in practice is more akin to a cross between a historian, a cultural translator, and a public advocate. This role places me in the space between two other worlds, the world of the housed and the world of the unhoused. Two worlds that live beside one another, and yet consist of two starkly distinctly cultures that seldom communicate or cross-pollinate with each other. In this role, I often feel like an ambassador or diplomat between two hostile nations, translating each side to the other, working between two cultures, brokering truces and fostering relationships, trying to stress their similarities and explain their differences to each other.

In navigating back and forth between the terrains of these two cultures, I inevitably end up in a wide variety of situations. Often, I find myself in settings around public policy, where I become an important voice for those who often end up on the wrong side of “quality-of-life” and “livability” measures. Other times my role is on the streets, acting as an on-call liaison between the police and the homeless, with the aim of diffusing tense situations and improving communication between the two groups. And sometimes the work requires an appeal to the public, with a need to raise awareness that often takes the form of direct action and civil disobedience. In such circumstances, I have sometimes found myself at the center of controversy, and as the public face with one foot in each world, I am often confronted with harsh questions, demands and expectations from both sides. It requires a constant maneuvering through minefields of both praise and condemnation while never forgetting to keep a clear focus on the truth.

Over the past two months, a spontaneous series of protests initiated by Eugene’s homeless community have become a focal point of controversy, further polarizing a community that has been split on the issue of homelessness for over thirty years. The protests, which have taken the form of tent communities on public land that are directly and deliberately in violation of Eugene’s camping laws, were started by homeless members of the SLEEPS (Safe, Legally Entitled Emergency Places to Sleep) community. Activists associated with SLEEPS, including myself, have been fighting for the right to sleep for nearly two years now, with an extensive campaign consisting of public protest and civil disobedience as well as actively lobbying and pressuring city government to change its laws and policies that negatively impact the civil rights of homeless people.

Last April, SLEEPS won an initial victory when the Eugene City Council agreed to modify the camping ordinance in order to provide some sort of legal places to sleep. However, in the months following that initial agreement, conditions for the homeless took a turn for the worst. The Federal Bureau of Land Management’s decision to rehabilitate the West Eugene Wetlands resulted in the eviction of nearly 200 people from a parcel of swampland west of town, where many have been living for several years. Meanwhile, the Eugene Mission, the only walk-in shelter in the entire county, significantly reduced the number of available beds per night due to staffing issues and an inability to handle large numbers. And while these events took their toll on the local population, resulting in a noticeable and significant influx of displaced homeless people into the downtown area, the City Council dragged their feet on the camping ordinance, suddenly hesitant and cautious after an extensive amount of community opposition.

The combination of recent displacements, broken promises, and renewed police sweeps came to a head in early August, when a homeless camper who was evicted from the wetlands pitched a tent on public land in downtown Eugene underneath the Ferry Street Bridge. He publicly announced that he was there in protest, and that his intention was to camp in the public eye until the homeless were given the right to sleep. Others soon joined him, and by the time police cleared the camp a week later, over twenty campers had pitched tents at the site. The protest immediately moved to the Free Speech Plaza in downtown Eugene, and within a day, the population had doubled. The Plaza could not hold such a crowd. We needed a plan.

Alongside taking in the history of Hoovervilles and the Great Depression, I had spent the months leading up to this point researching public property in the city limits, envisioning the various possibilities around modern-day Hoovervilles on public land. Numerous trips to the county surveyor’s office and the deeds and records department had eventually resulted in a thorough list of every publicly owned parcel within reasonable walking distance of the downtown core. Satellite images, property visits, and tax maps provided a base of information which up to that point had only held value for visionary purposes. Suddenly, standing in the center of a large group of people determined to camp on public land in an act of civil disobedience, my pile of notes from the surveyor’s office became invaluable and an idea was sprouted. A few hours later, I came back with maps and notes, and a few people immediately stepped up, interested in seeding camps of their own. And from the idea of Hoovervilles, the “Whovilles” were born.

Alongside taking in the history of Hoovervilles and the Great Depression, I had spent the months leading up to this point researching public property in the city limits, envisioning the various possibilities around modern-day Hoovervilles on public land. Numerous trips to the county surveyor’s office and the deeds and records department had eventually resulted in a thorough list of every publicly owned parcel within reasonable walking distance of the downtown core. Satellite images, property visits, and tax maps provided a base of information which up to that point had only held value for visionary purposes. Suddenly, standing in the center of a large group of people determined to camp on public land in an act of civil disobedience, my pile of notes from the surveyor’s office became invaluable and an idea was sprouted. A few hours later, I came back with maps and notes, and a few people immediately stepped up, interested in seeding camps of their own. And from the idea of Hoovervilles, the “Whovilles” were born.

The first Whoville split off from the main SLEEPS protest within a few days, with a group of ten people who sought out a quieter area with the intention of shifting their focus from protest to forming a community. Their message was simple and clear: we are just like you, and homelessness can happen to anyone. They set up camp on a publicly-owned strip in front of the county fairgrounds, across the street from a row of houses. Within a few days, a second Whoville split off from the first, setting up camp a few miles away on a piece of county-owned property. After the first Whoville was evicted by police, they joined up with the second again, and when the combined encampment of 50+ people was forced to leave the county lot, they once again split in two and occupied two more public parcels. And thus began a game of cat-and-mouse between a determined tent community and the local police department, a game that continues as to the time of this writing, with a Whoville setting down on another parcel every time they are evicted from the last one. Every time they are forced to move, the Whoville community tightens, and their constant visibility and orderly habits have won them a significant amount of public support. And through it all, my time has been split between the world of the camps and the world of police and city officials, a never-ending back and forth, keeping both sides constantly apprised as to the next steps of the other.

The police understand their role in the cat-and-mouse game all too well, and are just as reluctant to move the campers as the campers are to move. The futility of this dance is equally evident to both parties, and the police have hit their own peak of frustration in a similar manner as the homeless. Their job requires that they enforce laws that many do not feel are fundamentally fair and just, and they enforce the camping law under orders while knowing full well that the people they cite have nowhere to go and no other option. The police are under significant pressure from upper management and the business community to step up enforcement, while at the same time community activists and civil rights lawyers constantly pressure them to relax their enforcement. They are caught between two worlds themselves, and the constant convergence of oppositional influences leaves many on the force with a muddied view of what it means “to protect and serve”. Overall, the police aren’t nearly as concerned with homeless people camping on public property as they are about the potential for violence against people in the camps.

The second incarnation of Whoville on River Road in Eugene.

As was to be expected, the spontaneous tent camps popping up throughout the community sparked outrage from the NIMBY (“not in my back yard”) crowd and from those who harbor prejudice against the homeless. Local media outlets, most of which are conservative in nature, effectively fanned the flames of anger and hate by focusing their coverage of the camps and protests on the fear and negative reactions, as opposed to the actual message and its effects. Social media sites lit up with hate-filled insults directed at the protesters, anonymous threats, and rhetoric that encouraged violence against the camps. At the height of my distress, I remembered a quote from Gandhi: “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” As disturbing as the display of hatred was to us, especially in a “liberal” community that prides itself as a “Human Rights City”, the hateful energy directed at us was a powerful reminder that we were gaining traction, successfully pushing the issue, pulling people out of their comfort zones. On one level, rather than be intimidated, I took to viewing such threats as an indicator of our progress. At the same time, the threat of violence and property damage had become a reality. Bottlerockets were thrown into a Whoville camp from a passing car. A porta-potty has been stolen, another was tipped over. But rather than acting as a deterrent, such incidents only strengthened the will of those in the camps and their supporters. Their determination to remain in the public eye has increased and deepened.

And so the roving camps continue, with the Whovilles and the local police seemingly caught in a neverending cycle of relocation and eviction with no true resolution in sight. Meanwhile, after five months of stalling and deliberation, last Monday the City Council finally passed an ordinance creating a pilot program for small homeless camps. While this is a positive step in the right direction, it will only serve a small percentage of the community, and the reality remains that there are a few thousand people in this town who will not have the legal right to sleep this coming winter. While the public outcry has died down somewhat since the Council’s vote, the protests and camps will likely continue into the foreseeable future, as they are literally colonies of refugees with no legal place to stop and rest. And for as long as they remain in the public eye I will remain there with them, trying to express to the housed community how the other half lives, trying to reason with the powers that be as to the needs and rights of the disenfranchised, and trying my best to provide support and encouragement to an overlooked underclass that has shown remarkable courage by deliberately placing themselves in the public spotlight.

I often sense that the invisible yet often-impenetrable borders between the two worlds are fading ever so slightly, and my long-term hope is not only that the homeless community will be granted the right to sleep, but that eventually the cultural differences between the housed and unhoused will no longer serve as a basis for building up walls. I hope that one day, walking between these worlds with diplomatic intentions in mind will simply no longer be necessary.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

May I just express my heartfelt admiration for your work and for the tireless work of he many unhomed citizens who are also working in this cause.

Thank you. 🙂

I echo what Anna has written. I’m not organized enough to spearhead such work as you do, and the Whovilles do, but I’m happy to support these efforts and movements as much as I’m able.

Maybe it would be good to understand the businesses whose customers are being driven away.

With all due respect, that’s an oversimplification built on top of an assumption.

I’ve taken the time to understand the perspective of businesses who fear that the homeless drive away their customers. And its just that – much more of a fear than a reality. Downtown Eugene has been stagnant for forty years, and the homeless have been labeled the “problem” for at least half that time, but in the past year, people have opened businesses under the “if you build it we will come” philosophy, and those businesses are thriving despite the homeless people in the area. Its not that homeless people drive away business as much as it is that fear about homeless people driving away business keeps people from opening businesses. Speculation and perception do not equal reality.

In the six weeks that the Whovilles have been setting up throughout Eugene, there have been two concrete instances of businesses claiming that the homeless camp hurt their flow. In the case of one business, who was by far the most vocal complainer, any actual effect to her business was a self-fulfilling prophecy that was a result of her own actions, not the camp down the street. She admitted to the news that she feared the homeless, she locked the door of her business and hung a sign on the door that stated “for security reasons, please knock”, and then she complained to every news station that her walk-in customer rate was on the decline because of the camp. It wasn’t the camp, it was her sign that drove business away. Your just warned all of your potential customers that they had something to be afraid of!

The camps are actually increasing many types of business where they set up. Homeless people have spending power too, despite what many tend to think. It may be in the form of food stamps as opposed to cash, but local restaurants and convenience stores have benefited by the presence of camps in the area. And although I do not believe that the camps are negatively affecting businesses to any significant extent, even if they did, my bottom line is this: Economic prosperity should not be valued and prioritized over basic human rights. There is a balance that can always be reached.

“Economic prosperity should not be valued and prioritized over basic human rights.” Beautifully stated and something that too many in our modern, predatory capitalistic society, have lost sight of. If we can’t have economic prosperity which lifts all of society up then what good is it?

My concern isn’t so much for the downtown businesses (though yes, there is a huge impact since you can’t walk a single city block without being aggressively hit up for change at least three times and way worse if you’re a woman) it’s the impact to our city’s ecology and wildlife. I do a lot of my writing and spontaneous devotional work in our city’s parks, especially Washington-Jefferson. One of the reasons that I liked that park in particular is because it was home to a ton of wildlife. I could sit there and be sure that I’d see squirrels and birds and if I was lucky some raccoons and nutria and a couple other large animals. Then Occupy Eugene set up camp in the park until they were kicked out for noise and violence and drug use and being a menace to the neighboring businesses. (I put in a couple shifts at the convenience store right across the street from there too, so you want horror stories about what these people did, I got them in spades.) The Occupy folk completely destroyed the park – tore up all the grass, left large pits, there was overflowing human waste and graffiti everywhere. And they didn’t lift a finger to clean up after themselves. The city had to send in teams to clean the shit up (literally!) and then fenced off half the park for about six months. Well, the ground is level and all the grass is back but I can tell you that the ecosystem has not fully recovered. All the animals learned to stay away and most haven’t returned though it’s been a couple years now. And this same thing is going on throughout all our parks and wetlands and other natural areas. You can’t go to these areas without finding signs of illegal camps (wrappers indiscriminately tossed everywhere, clothes strewn about, often beer bottles and needles left for children to find) and the homeless activists won’t address the issue because you actually have to admit that there’s a problem before it can be fixed and they’re too busy feeling persecuted by the government to do that. And don’t get me wrong, I’m not siding with the city here. They are being just as stubborn and pig-headed and blind as the other side and part of the reason why the homeless are forced out into these natural settings is because the city won’t consider any long-term solutions. This is an issue with a whole lot of grey to it, though you wouldn’t get that impression from either the Register-Guard or the Eugene Weekly’s coverage of it. But when it comes down to it, my side is always going to be with wild nature and the animals.

Just to be clear I don’t think that the homeless are doing this because they are horrible and inconsiderate people. The community has just marginalized and reviled them for so long and refuses to consider any valid, long-term solutions so the homeless have just stopped caring about anyone or anything but themselves. That is a collective failure and needs to be addressed before anything else can be done.

Its not so much that they’ve stopped caring, but they often simply don’t have the means, resources, and/or abilities to take care of themselves or the areas around them. I also don’t necessarily agree that they don’t care about anyone but themselves. A lot of the behavior actually comes from the opposite – that they don’t care about themselves at all any longer. So many have lost hope, are literally just waiting to die. They’ve lost all sense of self-worth and self-respect, and have been marginalized for so long that they literally feel invisible.

It’s a shitty situation, no one denies that. I was talking to a homeless guy the other day and he said the problem is that folks on the street lack a sense of purpose. He tried to fill that by organizing work crews so people could go around collecting cans and picking up litter. He felt this more than charity would give folks a fulfilling a vital role within the community. However, both local businesses and government opposed their efforts because they were concerned about cost and risk. And that’s what anyone who wants to change the situation faces.

Yes, this I completely agree with. Every effort to lift people out of their situation is met with opposition. Government and businesses complain while exacerbating the situation at the same time. There’s nothing for people to do, and anything they try to do meets a wall of some sorts. And then they’re characterized as lazy for not doing anything.

“when it comes down to it, my side is always going to be with wild nature and the animals.”

Likewise. Always.

I agree with your overall point, but you’re misrepresenting a lot of what happened at Washington-Jefferson. Yes, I agree that the camp caused ecological damage to the park. But it wasn’t “the Occupy folk” as a whole who destroyed the park… most of them actually tried as hard as they could to keep the park in the best condition they could. It was a small minority that caused the majority of damage, and that minority mostly consisted of those who suffer from illness or drug addiction. It only takes a few to ruin it for everyone. Occupy didn’t even want to be in that park. That’s the only place the City would let them go.

And to say that they didn’t lift a finger to clean it up is an outrageous lie. I was there as park of the cleanup crew in that park. We spent DAYS cleaning it. We cleaned until the City kicked us out, and would have stayed longer if they hadn’t. All of this is documented. Occupy even offered to rehab the grass but the Parks Department did not take them up on it.

You’re also really off by saying that homeless activists won’t address the issue of litter in the parks. We address this issue CONSTANTLY. I’ve been out in the wetlands on a regular basis for a few years now, trying to help people with sanitation, long before most people even knew it was an issue out there. I’ve been hauling trash out of the Whovilles nonstop for six weeks now. Trash and sanitation issues are a HUGE problem, but its an inevitably when people are forced to hide and do not have access to proper sanitation. If there were places to put their trash, they wouldn’t leave trash everywhere. If there were places to go to the bathroom, they wouldn’t be going in the woods. You’re right that they’re forced out there because the city refuses to consider long-term situations. But you can’t really blame people for living like animals when we’ve given them no choice but to live that way.

I saw what I saw. I hope you’re right and there was more going on than what was visible.

And the devastation of the park wasn’t just the result of a couple bad apples. In fact, everyone who caused problems in the community and the stores had Occupy badges and bandannas and otherwise affiliated with the movement. You may not want to claim them and they may not even have been there for political or philosophical reasons (populist groups ALWAYS attract such opportunistic parasites and bottom-feeders) but Occupy didn’t do enough to police it’s own, and the community noticed that they weren’t there afterwards. Too busy with the next big cause. THAT is why you are having trouble now. It’s all about public perception and you guys screwed the pooch. You want to be successful, do a better job reaching out to the community and winning their hearts and minds. That’s real, hard work though – not as satisfying as adolescent rebellion.

And please don’t feel that I’m holding you personally accountable. I like you. I respect the work you’re doing. And I’ve said these same exact things to other folks in Occupy and usually just get blown off. When I brought up the issue about the animals, in fact, one guy said “Fuck the animals. Our right to housing trumps theirs.” Since then I have smiled every time Occupy and related groups have met with failure in this city.

I still maintain that it was a small minority. There were 500+ people who cycled out of that park over the six-week period. Even if it was 40-50 people who were causing trouble, that’s still less than 10%. You’re right in that there were a lot of leeches and bottom-feeders, but you’re misrepresenting the circumstances when you say that Occupy “didn’t do enough to police its own”. Occupy wasn’t allowed to police its own. The real police prevented them from doing so. They dropped off every troublemaker in town at that camp, wouldn’t allow Occupy to exclude people, wouldn’t prosecute crimes that occurred in the camp, and wouldn’t assist at all in dealing with the violent and/or mentally ill. They made it impossible for Occupy to police itself. As for your statement that “the community noticed that they weren’t there afterwards”, what on earth are you talking about? They were there until the day they were locked out of the park, and then they all went into emergency mode to deal with the 200-300 homeless people who were back on the streets all at once, both in the Whit and downtown. The “next big cause” was people literally freezing to death in the streets, and they were dealing with that overtime. What was the community not noticing Occupy doing that could possibly have held precedent over that?

The reason we’re having trouble now has little to do overall with Occupy. City government has been resisting homelessness efforts for thirty years straight. There’s a long history of this. If anything, Occupy has helped us to a certain degree in terms of keeping the issue above-water. And I don’t know who you’re referring to when you say “you guys”. The folks who are behind the recent efforts are in large part not the same people from Occupy, and most of those who were affiliated with Occupy were well-known as part of old-school activist organizations in Eugene long before that. I’m sorry you haven’t had positive experiences with a lot of the Occupy folks. Frankly, I’ve had issues with many people in Occupy over the past few years, but I’m not going to condemn them as an organization because of it. What they’re fighting for and what I’m fighting for is much more important than anyone’s ego or satisfaction. I like you as well, but the fact that you would find humor in Occupy’s failures because you have personal issues with a few of their members when people’s lives are literally on the line in terms of what they’re fighting for does not sit well with me at all.

Ah, see that’s interesting. I didn’t realize that there were such large divisions among the activists. I assumed that these groups were all pretty much drawing members from the same pool of people and that produced considerable overlap since it’s not a very large pool to begin with.

I did not know that the cops just dumped undesirables in the Occupy camps and wouldn’t let the group expel them. That’s quite brilliant, actually. I mean, if I wanted to thoroughly discredit the opposition that’s exactly what I would do. And after I had stoked the community’s hatred for the group I’d stage a violent incident that could be pinned on them, so … moral of the story is be happy you don’t have Sannion in charge.

Lastly, I didn’t say that the next cause was unwarranted. Anyone who’s trying to create any sort of significant change in the world is going to come up against the intersection of too many things to do and not enough resources to do them with. When that happens people prioritize and things get lost in the shuffle. It’s inevitable. I simply have different priorities. But that’s why you’ll never see me out there on the picket line. Well, that and I tend to believe that peaceful protest is an ineffectual means of enacting political change in a capitalist system.

“…peaceful protest is an ineffectual means of enacting political change in a capitalist system.”

Agreed.

There are HUGE divisions among the activists in this town. There is a certain amount of overlap, but more often than not there are very stark lines drawn in the sand. Although you;d also be surprised at how many of them there actually are. Old lefties are constantly crawling out of the woodwork.

I give the police a lot of credit for their strategic brilliance, as awful as it was to be on the wrong side of it. They knew EXACTLY how to destroy the camp. It was incremented step-by-step, with a lot of pointers and suggestions from the Feds, and it worked perfectly. I usually worked early-morning security, and every day we would get guys just released from Lane County Jail. They ALWAYS told me that the police sent them there, told them it was a good place to get food and warm clothes. I remember trying to find a pair of shoes for a man telling me all about how he served 15 years in Coffee Creek on one count of rape and two counts of manslaughter. And then he decided he wanted to live at the camp, and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. And the violent incident was completely set up by police and pinned on the camp. Witnesses saw police drop the guy off. He was a right-winger who was drunk and looking for a fight. Perfect storm.

I also believe that peaceful protest is altogether an ineffectual means of enacting change… that’s why after Occupy I started focusing on working as an intermediary between the oppressed and the oppressors, so to speak. I find that working with both groups directly, mostly out of the public eye, is a much quicker route to getting things done.

It worked fine for the civil rights movement.

We have them in Seattle, too, like any city–they’re being called Nickelvilles. (After the mayor who seems to have declared war on the homeless.) As I visit an old friend in Everett, who by necessity eats at the community meals a lot, most of the homeless I know or borderline homeless, are in Everett, but it’s the same thing. I’m glad you’re able to work with them.

One thing Seattle’s doing is selling the Real Change newspapers. Those who want to be vendors do have to be vetted, and they were picture ID to indicate they were vetted, but the first bundle of papers costs the vendor nothing and they sell for two bucks (recently had to go up because of costs.) I think the cost to the vendor now is around a buck fifty per paper (not utterly certain of that number) but the paper has news of what’s happening around the city with homeless and unemployed and poverty issues, plus a section just for and by young homeless people. Selling the paper has been a way for vendors to get a hand out of their homelessness or just enable them to live a little less hand to mouth.

I wish I had the stamina to do the kind of work you do, but alas, I’m an activist online and where I can be. It’s one of so many issues that need attention. Thanks for doing what you do.

I was a fervent community journalist in my ill-spent youth. You have just shown me the ultimate cutting edge of community journalism. Bless you.

One thing that is missing in your history is Ronald Reagan shutting down mental hospitals inthe 1980–that turned loose a new kind of homeless– people who were deemed insane, and now had no place to stay, no one to ensure they took their meds, and who were now victimized on the streets.It was a big change and was different from the economic refugee homeless of the same period.

I appreciate the work and activism you do, but I, too, have seen wild animal displacement at a local Bay Area Occupy movement agricultural encampment– wild turkeys left their open land and moved into nearby residential areas, where they caused damage to gardens while seeking food, and engendered cries for their removal. They, too, had been rendered homeless, but unlike the economic homeless, they were unable to organize.

I was a neighborhood activist in the Coventry Village neighborhood of Cleveland Hts, OH, at the time or Reagan’s deinstitutionalization. Released mental patients in the region tended to gravitate to Coventry, where they knew they’d be treated with more tolerance, and they did make an impact.Coventry managed to absorb those folks more or less adequately, but the Coventry community was socially sinewy, with an active watchdog organization, neighborhood newsletter, involved elementary school PTA and neighborhood merchants association. Occupy afaik lacks this institutional stamina, alas.