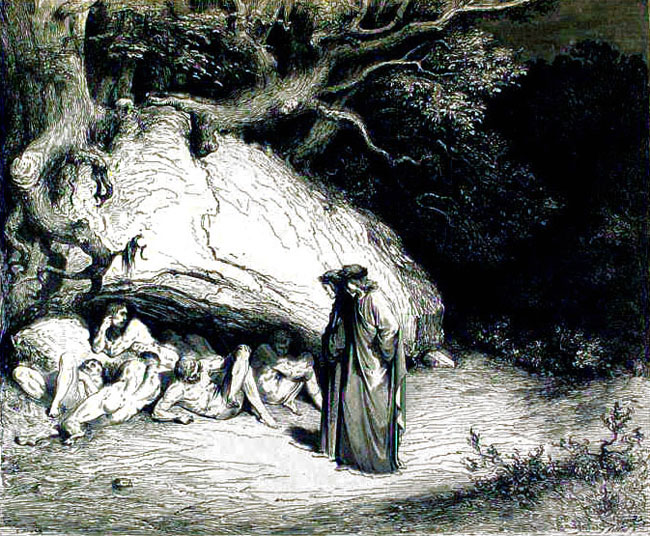

Virituous Pagans in Limbo, from Dante’s Inferno.

Gustave Doré, 1890.

“I’ve got a question. You know Eric, right?” asked Tim.

He and three more of my friends, Dylan and Lydia and Calvin, had just sat down to lunch. They were at a buffet off Highway 63 in Kirksville, Missouri, the town where we all went to college. I wasn’t there to see it; Tim didn’t tell me this story for months. I don’t know why he decided to ask these questions. Hoping to prove a point, I guess.

They nodded and wondered why he asked.

“Would you say he’s a good person?” asked Tim.

The three of them nodded. Sure, more or less. They were my friends, and they wouldn’t have been my friends if they thought ill of me.

“Okay then,” he said, eager to spring his trap. “Do you think he’s going to Hell?”

Calvin, who didn’t know me as well as the others, and who was in any case a committed and conservative Christian, said yes, absolutely, with no hesitation at all. Dylan and I were closer – close enough that I was his Best Man several years later. He said that he didn’t know for sure, but questions like that kept him up at night.

Lydia looked down into her lunch, didn’t answer. Tim pressed her, until she finally, quietly, replied. “Yes.”

I don’t blame her. Sometimes I think so too.

* * *

What happens to you when you die?

It’s the most common question I’m asked after people find out that I’m Pagan, after “Wait, really?” and “Can you fly?” I guess it’s a reasonable one. Christianity – or at least American Protestant Christianity – defines itself by the afterlife: it’s the point of the exercise. Heaven and Hell, and a life on Earth spent bumbling towards one or the other.

So, in the US, a nation of mostly Protestant Christians, it’s the question that shapes everything we think about a religion, whether or not we, ourselves, are Christians. Nobody in the public sphere ever discusses Islam’s Five Pillars, but everybody knows about the supposed 72 virgins. I doubt most could rattle off the Four Noble Truths, but we all know Nirvana means something more than the guys who recorded Nevermind. Because the afterlife is the foundation of Christianity, we expect it to be the foundation of everything else; a religion without an afterlife, that doesn’t worry about the afterlife, doesn’t seem like a religion at all.

What happens when you die?

There’s the trouble. I don’t know. I don’t even suspect.

The beauty of eclectic religion lies in its vastness of possibility – that anything could be true. Why choose? We speak of the immaterial and the transcendent, things that can’t be quantified or proven. Why can’t they all be true?

Well. That’s easy to say, so long as we’re only talking about generalities. Particulars are harder. When it comes to one’s own soul – to my own soul – well – I mean – something has to happen. Right?

If I were a better Heathen, I could confidently say I would go to Hel. (Being a portly coward, I doubt Valhalla is in the cards.) It sounds like an okay place. The landlady could be nicer. The Greeks give us the various suburbs of Hades: Tartarus, the Asphodel Fields, the blessed isles of Elysium. (Elysium, another home to valiant warriors, also seems like a stretch.)

Perhaps the Summerland? I heard about that one sometimes, growing up, though it seemed altogether more vague than the others: endless August afternoons, rolling hills and blue skies and warm breezes. Since the Summerland is a Wiccan idea (albeit one we stole from the Theosophists, like so much else), there is some variation: the Summerland might be an eternal summer vacation, or it might be a pleasant layover between trips. It may be the place where you survey your past life and plan out a new one, a tourist at the Triple-A station of the soul.

Yes, reincarnation: a popular option. Wicca conceives of time in a circle, after all: day gives way to night gives way to day, the Wheel of Year turning again and again. So perhaps we live, we die, we’re born again; no afterlife required. Hoof and horn, hoof and horn, all that dies shall be reborn.

But as much as I like the idea, I worry that it’s too appealing. It opens the door to vain recollections of past lives among the powerful and infamous. Whatever you do in this life doesn’t really matter, because you used to be Arthur Conan Doyle, or Hatshepsut, or whoever you read a book about this year. Reincarnation is a perfect answer: the circles all come around. I am suspicious of perfect things.

There are others. The Guf, mystic birdcage of souls. T’ien and Tír na nÓg and Takama-ga-hara. The one my parents made up for me when I was a boy, the Grandmother Country, where my Grandma Mae sits in a farmhouse and watches over all our departed dogs and cats and hamsters. And that’s before all the spookier options: spirits, poltergeists, zombies…

Hundreds, thousands of afterlives, all potential destinations, all acceptable, all real – except for two, the two that can’t be, the two can’t be allowed. The two that, in my heart, I will always fear are the truth.

* * *

My dad once had a friend who called himself Image. He died when I was 18. Image was the tallest, thinnest man I ever met. He kept a shaved head and worked hard at being Goth. I don’t think he ever kept a job for long: at one point he mucked the elephant pit for a one-ring circus, and that was the steadiest work he ever found. Mostly he made art. My favorite was an ambient record called “Surfacing,” which sounded like the soundtrack to a drowning. He was into the occult, too – he and my father were in a magickal group together for most of a decade.

There was more to Image that I never knew about: drugs and fetishes and other things I never looked into. But he was a soft-spoken person, and he was always nice to me, and as far as I know, he never hurt anybody.

A year or two after he died, when I was home from college for a few days, my dad asked me to come with him on a trip. We got into the truck and drove for a little over an hour. We came to a part of Missouri I had never seen before, somewhere out in the country. We pulled into a graveyard and drove around, taking pictures of interesting headstones, drinking sodas. Finally, my dad parked the truck.

We came to a headstone near a tree, and my dad stared at it for a long time. It belonged to someone named Paul F. I’d never heard the name before. I realized, when I looked up from the headstone, that my dad was crying.

“If you’re going to walk around in my dreams,” he whispered, “you could have the decency to stop and say hello.”

We didn’t talk at first after we got back in the truck. Garrison Keillor’s voice filled the silence. We passed a little river, far from the highway, and then dad said, bitterly, “Paul F. ‘Freddy.’ Image hadn’t called himself that in a decade.”

He turned down the radio. “His father was a preacher. Ugly man, self-centered. Everything in the world was always about him. When his son ended up as a cross-dressing magician instead of a Bible-thumper, he took that as something horrible happening to him. And when Image got sick, that was something happening to him, too. Just another shame Image made him endure.

“I heard about what he said at the funeral,” my dad continued. He had been in California when Image died and missed it. “He didn’t say anything about Image’s art, or the things he cared about. He just said it was a wicked life cut short.”

My dad wasn’t quite talking to me; he needed me there, needed me to listen. He needed to purge the words from his mind. Rip away the bitterness. He needed a witness. I didn’t say anything. I let him talk. It was what he needed.

But I thought about Image, and Image’s father, and what his father must have thought while preparing that sermon – what it must have been like, for a man so sure of the afterlife to have been faced with a son beyond saving. He had outlived a child – awful enough – but had outlived a child he knew to be damned.

Knew. Knew for certain.

That kind of certainty looms large against one person’s doubt.

* * *

During my last summer in Kirksville, I spent a lot of time with my friends Harry and Jenn. We were at their apartment one night, had just finished watching one of Harry’s beloved B-movies, when the subject of religion came up. You know my opinions on the subject. Harry and Jenn are both atheists, though the amicable sort.

Jenn got more emotional about it than I expected, aided, perhaps, by the three glasses of wine she had put away. “There’s something about it I don’t think you guys understand. You’ve both always been the way you are now,” she said. She was right: Harry’s parents were atheists. Mine were Pagan. We had taken after them. “But me, you know, I used to be Catholic. That’s how I was raised. And let me tell you something: you never get over that. I know what I want to believe, how I want to act. But in the back of my head there’s always this fear: I’m going to Hell. And it doesn’t go away, ever, no matter how much I try to convince myself that I’m beyond all that now.” She paused, shook her head. “I’m sorry. It’s something you can’t understand.”

She’s right. I don’t know what it’s like to have been a part of that system, or to reject it. But I know what it’s like to be haunted by the bad dreams of a religion I’ve never followed, to lay awake wondering whether it would be smarter, or safer, or saner, to try and square myself with the God of Abraham.

Because sometimes I think about that lake of fire, and Lord, I can feel the sweat start to creep across my skin.

(By the way, if you like my essays here on the Wild Hunt, good news: my first book, The Lives of the Apostates, comes out on June 28th! It’s available in ebook and paperback. It’s a novella about a Pagan kid in the Midwest. It’s got Sabbat rituals, awkward kissing, theological debates, Julian the Apostate, and a hearse. Order it from your local bookseller through IndieBound, or buy it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble. For more news on the book, might I humbly recommend my Facebook page? Alright, end of shilling. Thanks! -Eric)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Fear is a powerful tool that many use, especially religious people. Spiritual abuse takes a long time to recover from. It takes lots of unconditional love and support.

As my grandfather says, “Doesn’t matter what you believe, its what you DO. Go do good, and the rest will sort itself out.”

What Christianity sells is fire insurance. Reading Joseph Campbell helped me get over lots of guilt and fear. Another helpful author and lectures is retired bishop John Shelby Spong.

I mean, I honestly think Christianity does offer more than that. It’s just unfortunate that it’s undergirded by the scare tactics of damnation.

Bravo, Eric. I shall share this widely.

Thank you!

Being a terrified Baptist as a child, I am of the opinion that teaching a child about hell should be prosecuted as child abuse, for it does terrible things to a child’s mind that it takes decades to finally get over, if ever.

I was raised Catholic, and I never thought I was going to hell.

In my early twenties, about the age you are now, I suppose, I contemplated going back to the Catholic church. I wanted more spirituality in my life, and Catholicism was something familiar, something I understood. Two things stopped me.

One was a prime reason I’d left originally, which was the role (or rather, lack thereof) of women in the Church. I could no longer align myself with a spiritual system in which I, as a woman, was “lesser.”

The second reason was that if I were to return to the Church, I would have to confess my “sins.” I contemplated my life since I had left, especially the joyous sexuality I had experienced. By Catholic standards, these were mortal sins which would condemn my soul for all eternity. I knew that was not true. It could not be true. Joy was joy, not mortal sin. So in that moment, when I knew I was not condemned and could not, ever again be Catholic, I became Pagan, even though it was years before I had that name to put to what I felt and believed.

When I left the Catholic Church at 15, a part of my brain said, “But not going to church each Sunday is a mortal sin!”. I shortly arrived at the conclusion that if I did not believe it its teachings, such a mortal sin was of no consequence, nor would it change my behavior. Got over that one right quick.

I think I applied similar kinds of reasoning, although with the question of “Can you live with yourself if, because of what you’ve decided, X happens?”, to a couple of other situations. Once I realized that X happening was nothing of my doing, but a control tactic, I went on my then-merry way.

I’m glad to know I’m not the only one that this happens to. The fear of eternal burning I mean.

My family is Christian, the entire lot of them and it always amazes me how easily and casually they can say “You’re going to Hell”. So very, very easily. :/

How can they do that? How can they be SO SURE that it’s the right path?? Once I read a book in high school and the quote:

“All truths lead to one truth, and all Gods to one God.” (I felt like I had discovered the meaning of life. lol)

And that for the most part has erased all doubt that I’m going to burn in hell.

I believe in afterlives. Lots of them. From Heaven and Valhalla to Tartarus and Sheol, via Nirvana and the oblivion of cessation.

What I believe is that people choose where to go, based on how they live their life. (With, perhaps, some deific interference, should there be inclination in that regard.)

People send themselves to the Inferno, no coercion needed.

Yup. That is absolutely what I’ve always believed, too — you get the afterlife you believe in. They’re all true.

I never suggested belief came into play…

Oh I’m a firm believer in Hell. There has to be some place to put people I don’t like.

“…wondering whether it would be smarter, or safer, or saner, to try and square myself with the God of Abraham.” A very practical thought.

But do you accept Jesus as your personal savior? Do confess your sins and take communion with the Roman Catholic Church? Do you proclaim “there is no god but Allah and Muhammed is his prophet”? Those are just three out of hundreds of options. Pick the wrong one and you’re just as damned as the rest of us libation-pouring, circle-dancing, goddess-worshipping Pagans.

The impossibility of knowing which version of monotheism is the “real” one is one of the reasons I was able to cast off the fears of hell that my childhood in the Baptist church had planted in my brain.

You can’t know. I’m going to follow what my heart tells me is true, and trust in the power of Love.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/johnbeckett/2010/05/beltane-universalism.html

For some reason, what you said reminded me of the old “Boyle’s Law Hell essay joke”, notably this bit:

“As for souls entering hell, let’s look at the different religions that

exist in the world today. Some of these religions state that if you are

not a member of their religion, then you will go to hell. Since there

are more than one of these religions and people do not belong to more

than one religion, we can project that all people and souls go to hell.”

http://www.pinetree.net/humor/thermodynamics.html

Pingback: Pagan Radio Network Afterlife | Pagan Radio Network

I am not that worried about death and I am a lot closer to it and my partner is even closer. Life is rather complicated and just figuring it out seems to take most of my time. Death, well I will find out about that, if there is anything to find out, when I die. Until then , even with all time limits of my age and health, I am still awful busy just living. I really don’t have time to worry about something that I can’t stop and that has been approaching from the day a sperm reached an egg. At any point of the trip I might have died, could have died, so actually nothing has changed. When it is time I will die, but until that point I will survive everything that comes at me. Meanwhile leave it to the Christians to look forward to what happens after they die. Obviously they haven’t appreciated being alive for a long time.

Meanwhile I have an interview with Eric coming out in the Litha issue of ACTION. Read more of his writings.

Pingback: Afterlife | Pagan Radio Network

I never really worried about the hell afterlife. I figure I am a pretty nice person, and let’s say when I die I was wrong and I do go to hell from a loop hole like not being a christian. I take just a little comfort in that if I end up going there then I know very well there are worse people than I am who will be in there too even though they are christian. The one that sits in the back of my mind that I don’t like is that nothing happens when we die. At least with hell you actually have an afterlife, and hey if it turns out like Dante’s Inferno I will only be in the first level which didn’t seem that bad since Virgil was pretty much walking around doing whatever he wanted.

Congrats on the book release!

Personally, I am a Pagan with more of a scientific mind, for lack of a better term, about metaphysics and the afterlife. While the stuff they brainwash you into when you were a child doesn’t completely go away unless you’ve had deep therapy (!) I found my personal answer of what happens after death thanks to the books of Michael Newton, an hypnotist who went to what happens between the lives of their patients thousands of times, and the results were astoundingly similar. Oh, and there is no hell according to this study, except the temporary one created by your own regrets and awareness of really bad things you have done in the previous life, or your over-attachment to the material plane after death

Blessed Be

Well, I think that religions are more than fear but what you’re describing is just fear. We all have fears of something though I think fears instilled by religion are probably the worst kind of fears, or abuse.

As a Pagan though I do believe in reincarnation, but it’s not quite the pretty picture you described. I doubt very much you can remember past lives or anything like that – and I don’t know that I’d say it’s even important – but just based on the fact that souls are energy, they’re probably recycled in some way. I just think that you kind of… disintegrate after everyone you know and have loved is gone, you just disappear until those parts of you are made into a new person and a new experience. Maybe there’s a way to transcend this or whatever – but I’m not too worried about it.

This is a perverse line of thought, and one of the exploits the unscrupulous use to get you to consider their point of view as anything remotely approaching sanity.

Not wanting something to be true not making it false does not mean the opposite: not wanting something to be true does not make it true. And given the absolute dearth of evidence and the perverse rendering of justice such beliefs entail, I feel comfortable not only dismissing them, but considering those who believe in them in that exact format (hell as a just punishment) to be either morally degenerate or likely in need of mental health care.

I believe you may have missed the point.

I’m uncertain why you think that.

The idea of afterlife is scary in one way because it’s unknown. The contemplations present in this article arise from a world which has been inundated with a perverse theology which exploits fears present in many humans, a fear that you can never “be sure” you’re right and that you may always feel at danger yet never able to know for sure.

It is my opinion that such fears are evil. Not that those who have them are evil, but they arise strictly from evil beings who are trying to trap your mind, and that the result of giving into those fears is to have evil inflicted upon you. It is my opinion that any meditations taken upon the aftermath of your expiration have those thoughts aggressively purged, or else they will seize you and destroy your happiness.

If you consider this to be an utter tangent to the article, let me know in what way, because as I said, I am uncertain why my musings seem to miss the point.

Ah, my apologies, then. I interpreted your comment as blaming Eric for being “unscrupulous” and for advancing “a perverse line of thought.” It seems I misconstrued what you wrote.

I believe there are mysteries, ie things that cannot be understood by humans. And death is one of them. So if a human believes s/he has understood a mystery, like death, s/he is mistaken. In that light, *all* clear, certain ideas about what happens after death must be mistaken.

On the other hand, if I die and it turns out that the Christian cosmology is true, I’m not sucking up to a jealous, angry male god. I’m enlisting with the other side. And I’m fighting.

Cheers,

Lucía

Considering that the other side is (by all accounts) male, also, I am unsure how the gender aspect has any relevance.