It has been a several months since the last installment in my series on Hollywood’s witches. Last May I explored the period from 1939 to 1950. During that time the witch evolved from a cartoon hag into a signifier of the empowered, sexualized woman (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs 1937 and I Married a Witch 1942). Now I will pick back up in 1950 just as television enters its Golden Age. During the subsequent eighteen years, the American film industry undergoes radical changes affecting its structure and product. The period ends in 1968 with the death of the Production Code and the birth of an entirely new Hollywood.

Courtesy of Flickr’s The City Project

There are four significant factors that forced that well-oiled Hollywood Studio System to break down. The most obvious is commercial television. In reaction to this new form of popular entertainment, the Studios had to rethink their processes. While aggressively competing for viewership, they also realized that TV could be a new venue for their films – both new and old. This led to a positive, long-lasting and lucrative partnership between broadcasters and Hollywood.

The other three factors were external to American entertainment. First, the Cold War Era’s House of Un-American Activities Committee indirectly censored movies and interfered in industry business forcing many “talented people to leave Hollywood.” Secondly, the 1948 Supreme Court Paramount anti-trust ruling required all Studios to relinquish their theater holdings. Fox Studios could no longer own the chain of Fox Theaters. Finally there was an increase in foreign film imports – none of which were censored by the Breen office. Their growing popularity forced the Production Code Administration to repeatedly revise the restrictions in hopes of selling more tickets. (Basinger, American Cinema, Rizzoli, 1994)

With all of that change and the impending Cultural Revolution, it is easy to understand how the Hollywood of 1950 was not the Hollywood of 1968. What happened to the witch between 1950 and 1968?

Between television and Hollywood, there were over fifty narrative programs containing a witch. More than any previously studied period. This increase is due to an overall increase in production. The witch begins to move beyond the realm of fantasy and cartoons into new genres. As a result, she transforms.

Dorothy Neumenn as Crone Meg Maud. Courtesy of Acidemic.blogspot.com.

From 1950-1960, the dominant witch character is a “Folk Witch.” She is derivative of the old “hag in rags” without the iconic pointy hat and other trifles. She is the reclusive crone who lives at the edge of town and dabbles in herbs. Often the folk witch talks to animals and speaks in rhyme. She is mischievous and morally ambiguous.

The first appearance of this witch is in Comin’ Round the Mountain (1951). In this Abbott and Costello comedy, the Folk Witch is played by none other than Margret Hamilton, the same actress who played the Wicked Witch of the West. This casting was very conscious.

Most of the other folk witches appear in popular western TV shows such as Gene Autry Show (1951), The Adventures of Kit Carson (1953), Wanted Dead or Alive (1958) or Maverick (1960). In “Healing Woman,” an episode of Wanted Dead or Alive, Josh Randall (Steve McQueen) tries to convince a man to see a medical doctor rather than the town’s “healing woman.” Randall says: “If you think that witch is going to cure a stomach full of poison with a handful of frogs, well…”

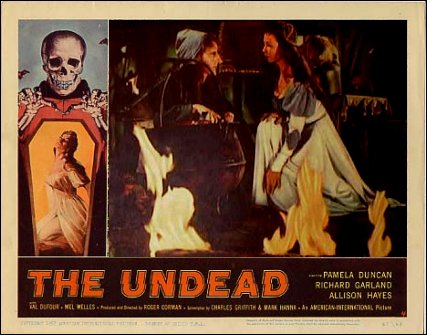

The folk witch isn’t the only evolutionary change in the witch. In 1957 the film The Undead set two precedents. Not only is this the first Hollywood Horror film to introduce a strong witchcraft narrative1, it is also the first film that re-marries witchcraft with Satan. The Undead has two witches: Meg, the helpful folk witch and Livia, the evil femme fatale witch. Through this film, these two wise woman archetypes are immersed in European mythology and a theological thematic that define their morality. Goodly Meg makes the sign of the cross. Evil Livia is his servant and, as such, one of the first Satanic Witches.

Courtesy of Picasa’s Todo El Terror Del Mundo

Up until this point the evil witch is bad without reason. The production code strictly controlled the representation of evil, especially that connected to female sexuality. The Code read, “No plot should present evil alluringly.” But times change.

From 1960-1968, the number of witch-themed horror films increase. However, the majority of these films were imports from countries like Mexico, Italy and the UK (The City of the Dead 1960). In such narratives witchcraft exists as an historical leftover – a long-forgotten “evil” that is unearthed from its proverbial tomb to haunt present day (The Naked Witch 1961.) Christianity is the moral counterpoint.

By the mid 1960s, even the otherwise harmless folk witch had become an agent of Satan ( The Terror 1963; Twilight Zone’s “JessBelle” 1961.) In The Terror, the folk witch burns up at a church entrance. In “Jess Belle,” the witch talks about selling one’s soul. The Satanic theme eventually affected the representation of witches outside of the Horror Film. (Alcoa Presents, “Make Me Not a Witch” 1959; Bonanza “Dark Star” 1960.)

![Torin Thatcher as Pendragon, the Warlock Trailer screenshot (United Artists) (Jack the Giant Killer 1962) [Public domain]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Torin_Thatcher_in_Jack_the_Giant_Killer_trailer.jpg)

Torin Thatcher as Pendragon, the Warlock Trailer screenshot (United Artists) (Jack the Giant Killer 1962) [Public domain]

The construction of the witch is mostly genre dependent. The “occultist” is usually found in revisionist fantasy or science-fiction where there is room for fantastical caricatures and shiny costumes. The folk witch appears mostly in westerns that depict frontier life. The Satanic witch, male or female, finds its home in horror or the like.

What about the classic Halloween Witch? Over this entire period, there is a marked decrease in the retelling of classic fairy tales. However, there is an increase in cartoons. This is where the Halloween Witch lives (Popeye; Milton the Monster; Tom and Jerry; Underdog; Caspar; Story of Hansel and Gretel 1951; Sword in the Stone 1963, e.g.) In some cases, the hag is the antagonist (Return to Oz 1964) and in other times she’s a helpful imp (Trick or Treat 1952.) In two cartoons, the witch is actually good: Caspar (Wendy) and Honey Half Witch. Bad or Good, all of these witches are reflections of American Halloween secular mythology.

Kim Novak in Bell Book and Candle. Posted with permission from doctormacro.com

There is one other genre that I have yet to discuss – the woman’s film. In 1942, I Married a Witch broke ground by introducing a live-action femme fatale witch (Jennifer) within a romantic-comedy. In the 1958, the story manifests again in the melodrama Bell Book and Candle. A young witch, Gillian, gives up her power for love and marriage. In the earlier film, witchcraft is clearly defined as bad through its connection to Salem. In Bell Book and Candle, witches are likable eccentrics and witchcraft is harmless child’s play. Gillian even celebrates Christmas, a Hollywood marker of a good person.

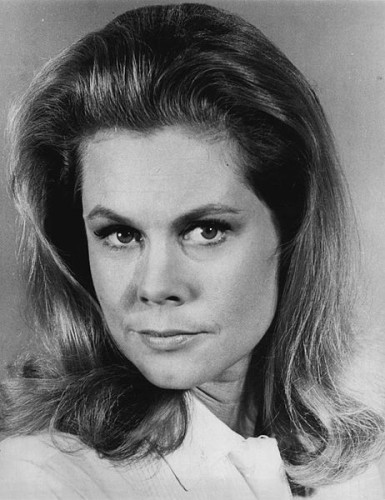

Finally, this period wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the second most iconic, fictional American Witch: Bewitched’s Samantha Stevens. Samantha, a traditional housewife, is the focal point of the sitcom. She propels the narrative and routinely saves the day. Unlike Gillian and Jennifer, Samantha retains her magical power in marriage and interacts with both the human and Witch world.

Publicity photo of Elizabeth Montgomery as Samantha Stephens in Bewitched

Bewitched is loaded with hidden cultural meaning that define the late 1960s. It is largely considered the first feminist show because of the challenges posed to the nuclear family and gender politics. Witchcraft is just a playful mask to attract audiences. The show is an allegory for the growing feminist movement and the battle for Civil Rights. Film Studies Professor Walter Metz remarks in his book Bewitched:

Bewitched also turns out to be an adult delight, engaging in a strong willed critique of discrimination of those who cannot or will not abide by conventional social mores.

This is a sign of things to come. In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America removes the restrictive Production Code. It is replaced by the rating system that is still used today. In the next installment, we’ll enter the Post Production Code 1970s – the era that birthed the teen slasher film. It is time when films radically change and things begin to get darker.

1 Most early Horror films were monster-focused with a few mentions of Voodoo or the Occult.

2 I use the term “Occultist” here to differentiate this type male witch from the others. It seems that these recurring archtypes are based on a gypsy motif or perhaps inspired in some way by photos and media caricatures of Aleister Crowley.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Ah, I thought I would be reading about the actual Witches who lived around Hollywood in that era. They included Robert Heinlein’s econd wife, “Amanda,” as well as many who became founders of the Pagan movement. But I’m working on that.

Glad to see you picked up on “Amanda” also. Once Patterson has finished with vol. 2 of his Heinlein biography and has time, I hope to get him to tell me a little more about the sources he has for “Amanda’s” witchcraft. He doesn’t really spell them out in vol. 1. — Shirley Jackson is also a California product, though she spent most of her life in the Northeast.

Was Amanda the model or the informant for the witch character in Magic, Incorporated? IIRC, the love spell incident and the things she says to the narrator about love spell ingredients are in line with Gardnerian magical ethics.

“Amanda” was the name of the witch in “Magic, Inc.,” and she is the most impressive and interesting character in the entire story. Her magic is drawn mostly from the English translation of Grillot de Givry’s French work on witchcraft and magic, with a nod in one detail to _The Circus of Dr. Lao_. In view of her name, Heinlein’s model for her is almost certainly his wife at the time, the remarkable Leslyn MacDonald. Patterson mentions that MacDonald practiced Witchcraft on behalf of her and Heinlein’s friends and (IIRC) called herself a Witch. He indicates that he has sources for this, but never gets around to doing more than mentioning one or two of them in the most general way. That was probably an oversight of his while putting all his ducks in order for vol. 1 of his Heinlein biography, which is a huge and detailed work.

PS I’m not entirely sure what to make of the close parallels between Amanda’s ethics of love spells and the Gardnerian ones. As an off-the-cuff guess, both were taken from early 20th-century discussions of the ethics of sexual expression and alternative sexualities. As I’m not particularly well-read in those ethics, it’s just a guess. Patterson does have some remarks on them in general, which seem in line with the story.

Those parallels may be more circumstantial given that Magic, Inc was originally published in the September 1940 edition of Unknown Fantasy Fiction, (under the title “The Devil Makes the Law”), long before the Gardnerian practice and ethics would have been well known outside of its members.

Looking forward to reading that!

Its no wonder “The Undead” was so stereotypical: it was a “quickie” (filmed in six days) Roger Corman flick put out to take advantage of the sudden interest in reincarnation engendered by the “Bridey Murphy” craze.

MST3K’s take on “The Undead” was one of their best efforts. Although “The Undead” is fun just the way it is.

One of the wackiest “occultist” appearances on television in this period, I think, was in the first season of The Wild Wild West (with Robert Conrad and Ross Martin), in which there was an episode called “The Night of the Blood Druid” (which, confusingly, never once mentions the word “druid” in the entire episode…!?!), in which Don Rickles (!?!) plays a Satanic magician who has used a bunch of scientists’ brains to create a kind of proto-computer. Conrad commented that it was one of the most unusual and strange episodes of the show they ever produced…and, it’s a simultaneous laugh riot and face-palm extravaganza. I’d highly recommend it!

On a somewhat related note, one of the movies mentioned here, ‘Jack the Giant Killer,’ was the feature of a live Rifftrax event that I was lucky enough to see in the theater. By the time it was over, my stomach and entire face hurt from laughing! It’s available on DVD here, and there is a compilation of some of the funniest bits on YouTube here.

Love this article series, I always find a few gems I had not heard of before. Will definitely check out a few of these.

The Star Trek episode “Cat’s Paw” is interesting on many levels, though having as close an understanding of Gene Roddenberry as Robert alludes to below of Heinlein is necessary, so I won’t dig up details for this post.

Main point: the aliens disclose that their dungeon and horror icon “trappings” were gleaned from the minds of the humans for which they used it. Roddenberry often used that plot device to comment on those icons and attitudes rather than to promote them.

Heather, I particularly appreciate the attention you gave to “Bewitched”. I thought “The Munsters” and “The Addams Family” would have been within the same span of years. Perhaps I misremember that, but in any event I’m just curious to see if you include them in your next installment.

The image of the crone with a long hook-like nose and chin started in the area of Germany and it surroundings in the late 19th C., IIRC. It was cariacaturing the profiles of old Jewish women, reinforcing the stereotype of the “evil Jew”.

Andre Norton’s Witch World Witches also tended to lose their powers when they lost their virginity. The younger me who read those books so many decades ago wouldn’t have thought to ask if the sex weren’t rape, would a witch keep her powers, as the protagonist had when she married for love.

I adored Bewitched as a teen–and suspect that I’d enjoy seeing it again. I wasn’t as aware of “race” and “feminism” then as I was even a few years later. I will have to bear that allegory in mind.

Another interesting chapter in this series. Thanx. “Boris Karloff’s ‘Thriller'” has a number of interesting episodes devoted to witches or witchcraft. Somewhat off topic (and although not Hollywood), for my money, the Mario Bava trilogy “Black Sabbath” features the most terrifying image of witch in the story “A Drop of Water”.