Our last stop on this cinematic journey was 1937 with the release of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Up to that point, the Hollywood witch had already evolved from a turn-of-the-century “clown witch” to a stereotypical cartoon “hags in rags” and finally into an animated femme fatale.

Throughout that early period, the witch was contained within the framework of fantasy. Even those few outliers created a wall of separation between reality and the witch. MacBeth (1916) is just a retelling of a Shakespearian drama. In the Witch of Salem (1913), the “witch” is a victim of hysteria. In film studies speak, the witch never threatens to enter into the viewer’s world.

The next period stretches from 1939 to 1950. It ends just as television begins its golden age. In 1947, the number of home televisions was in the 1,000s. By 1960, that number was well into the millions. That change presents yet another major technologically-based shift in entertainment consumption and production. (Mitchell Stephens,“History of Television,”)

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Courtesy of doctormacro.com

The period begins with MGM’s release of The Wizard of Oz (1939) – another retelling of L. Frank Baum’s first Oz story. Both Glinda and the Wicked Witch of the West are significant to this study. However, the Wicked Witch is by far a more powerful cultural icon and quite possibly the most famous of all Hollywood witches. She is even ranked #4 on the American Film Institute’s “100 Best Film Villains.” Since her birth in 1939, the Wicked Witch of the West has impacted, if not defined, what it means to be a “witch.”

MGMs’s Wicked Witch is an evolutionary step from the “hags and rags” cartoon motif. She has all the common elements including a broom, angular chin and nose, black clothing, a crystal ball, long fingernails, and a pointed hat. However, she’s much more intense and frightening. She was constructed as a bitter turn-of-the-century spinster who hates dogs and young girls. Her clothing is reminiscent of that era.

What about her green skin? Up to this point, there has never been a witch with green skin. Actress Margaret Hamilton recalls:

Black next to your skin seemed to give rise to a thin line of white on the edge of the black, which did not look like edging but rather like a separation. But with Oz the problem was solved… that was why they chose green makeup for my face, neck and hands. (Aljena Harmetz, The Making of the Wizard of Oz )

The green-skinned witch was born. Why green? The color references other monstrous figures such as Frankenstein and suggests sickness, envy and even the undead.

In the original story, Baum described Oz’s other witch as an oddly-dressed old woman wearing white. But MGM changed Glinda into a younger angelic creature with a fairy-like appearance. She descends gracefully from the heavens in bubble that surrounds her like a golden halo. Always appearing in soft focus, her face is perfectly framed in blond curls. Glinda sparkles as symbol of purity in pink, silver and tulle.

Billie Burke as Glinda

Courtesy of doctormacro.com

The film version of The Wizard of Oz (1939) is only a loose adaptation of Baum’s original story. The visual appearances and narrative roles of both witches were altered in order to increase drama and remain within the Breen Code. The film’s witches are the polar extremes of good and evil.

Interestingly MGM interjected a bit of religion into the story in order to develop character. Auntie Em calls herself a “good Christian woman” when defying Mrs. Gulch. This statement an example of an old Hollywood technique that was prevalent during the Production Code days. If something is defined as being Christian, anything counter to that must then be bad. As such, Mrs. Gulch (a.k.a. the Wicked Witch) was set-up as evil right from the beginning.

When the film was released, The Wizard of Oz received only mixed reviews. Regardless, the Wicked Witch left an immediate and indelible imprint on American entertainment. In 1942, Sky Princess, a a stop-motion, Puppatoon short contained the next in a long-line of green face witches. In Comin’ Round the Mountain (1951) actress Margaret Hamilton makes the first of many reappearances as a witch. Since 1939 there have been countless films, television programs, books and even Broadway shows that have, in some way, drawn from that one single movie.

Aside from The Wizard of Oz and The Sky Princess, there were only five other “witch” movies released from 1939-1950. Three of these films are shorts containing a typical Halloween style “hag in rags.” One of these is a Mighty Mouse cartoon called Witch Cat (1948). The second is another animated short called The Bookworm (1939). The third is a live-action film called Third Dimensional Murder (1941) which showcased early 3-D technology. These latter two films are the first to directly associate the witch with classic monsters such as Frankenstein or Dracula.

In 1948, Orson Wells remade the classic play MacBeth with an interesting new twist. This film marks the first time a witch is equated with a real religious practice outside the bounds of Christian iconography. In his book This Is Orson Welles, Welles wrote:

The main point of the production is the struggle between the old and new religions. I saw the witches as representatives of a Druidical pagan religion suppressed by Christianity – itself a new arrival… the witches are the priestesses. (Welles, pg 214-215)

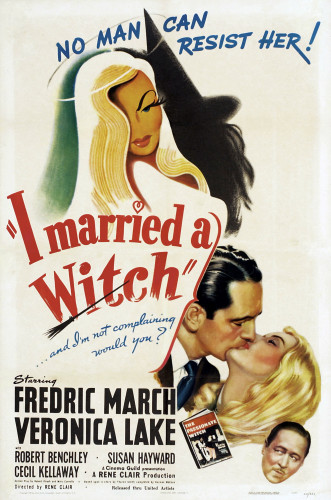

This takes us to the final film of this segment: I Married a Witch (1942). In this film, the witch steps out of the fairy tale or Shakespearian play to become a part of the mortal world. Its two evil witches, a father and daughter, take on the appearance of normal humans. The only typical witch icon used within the film is the flying broom. The daughter, Jennifer (Veronica Lake) is a coy, sexy femme fatale and her father is the male version of the clown witch. He’s both the comic relief and antagonist.

This takes us to the final film of this segment: I Married a Witch (1942). In this film, the witch steps out of the fairy tale or Shakespearian play to become a part of the mortal world. Its two evil witches, a father and daughter, take on the appearance of normal humans. The only typical witch icon used within the film is the flying broom. The daughter, Jennifer (Veronica Lake) is a coy, sexy femme fatale and her father is the male version of the clown witch. He’s both the comic relief and antagonist.

I Married a Witch is unique because it was made specifically for female viewers. It’s a variation on a theme prevalent during the World War II era. As Jeanine Basinger states, “..the woman’s film juxtaposes in unrealistic ways two contradictory concepts: the Way Women Ought to Be and the Other Way.” These films gave women the opportunity to temporarily step out of societal expectations and explore the “other way.” However, they always end with marriage and the acceptance of traditional roles. (Jeanine Basinger, A Women’s View)

In I Married a Witch, the “other way” is “witchcraft” and the “Ought to Be” is love and marriage. In the end, Jennifer proclaims “Love is stronger than Witchcraft” and, as a result, is lead from a sinful immortal existence to a traditional life of family and marriage. In the final scene, she is shown quietly knitting with her long tresses piled neatly on her head. The father, who never accepts the proper role of the “good father,” is forever trapped in a liquor bottle.

The Hollywood witch is slowly transforming into a symbolic representation of femininity, but only the sexual, the independent, the free, the powerful and the creative side. The only way that she is allowed to live is through the acceptance of goodness through marriage, tradition and children. Even Glinda’s power is limited to the care of the munchkins and a child. Although the witch still appeared as a cartoon anecdote, she developed this new side – one that will continue to evolve as society changes.

In the next period, we enter the days of television. Let the battle for viewers begin…

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

It’s worth pointing out that “I Married a Witch” is the precursor to the “Bewitched” TV show, a huge hit 20 years later. But that’s for another article!

One of the most interesting things about “I Married a Witch” is that in it, witchcraft is worked in families, or groups of connected families, not in covens. The same meme is there in “Bell, Book and Candle” (1958). After that, it takes off in American culture.

At about the same time the cartoons of Charles Addams begin to appear in The New Yorker and elsewhere, featuring his signature weird family. These two developments are probably not unrelated.

Yes It is an interesting observation. There is family “witchcraft” in The Wizard of Oz too. (Another detail not taken from the book) Unfortunately, I can’t include all observable details in a single post. This particular point is on my radar. I agree that there are some interesting ideas that can be drawn out of this about the nature of witches in fiction.

You forgot to mention that they’re two good witches in the original Oz book and that they are combined in the movie. The oddly dressed woman whom you described was The Good Witch of the North, not Glinda. She is the Witch of the South in the novels.

Hi Ryan. Excellent point. I didn’t mention it. There were so many changes made from the original to the movie. More than I could ever include in a post but will be included in my longer version.

Just wanted to say how much I enjoy this series. Very cool info about why the Wicked Witch of the West is green – there have been a few wacky theories about that circulating in pagandom so it’s nice to have an answer.

While I like the clips I have seen of I Married a Witch I get a twinge about it kicking off the trend of films in which witches lose their powers if they fall in love.