How many of our modern problems are caused by people being raised to read religious texts literally?

I think about this question often.

The fundamentalist urge to point to ancient written sources and insist that they say what they say, they mean what they say, and we must do what they say comes from mindsets that are not unique to evangelical Christianity or radical Islam.

There’s a seductive pull to the position that insists the composers of the earliest texts had access to a purer form of a given religion than any later practitioners, priests, or theologians. The fallacies of appeal to authority and appeal to antiquity merge to form a cudgel used by today’s fundamentalists to beat down those who dare to disagree.

Wisdom and Strength by Paolo Veronese (c. 1565) [Public Domain]

For those who participate in the new religious movements of Ásatrú and Heathenry, literalism and fundamentalism are somewhat strange stances to take. Given the mediated nature of the surviving texts and the ocean of secular academic theorizing that surrounds (and sometimes drowns) them, it’s difficult to claim access to any sort of pure pagan worldview of the ancient Germanic world. And yet, exactly such access is often claimed.

The vaunted Icelandic sagas are works of historical fiction composed by Christians several generations after the island’s national conversion to the “new way.” The Edda of Snorri Sturluson is a poetry manual based on classical European literary models, and it’s also composed long after Iceland’s conversion. The texts that come closest to preserving pagan voices are the small collection of mythological and heroic poems we now know as the Poetic Edda.

What are we to do with these poems? How can we read them in religious context today?

In Ásatrú, as in other religions, there is a conflict between literal reading on one hand and moral or allegorical reading on the other.

“Dauntless in action”

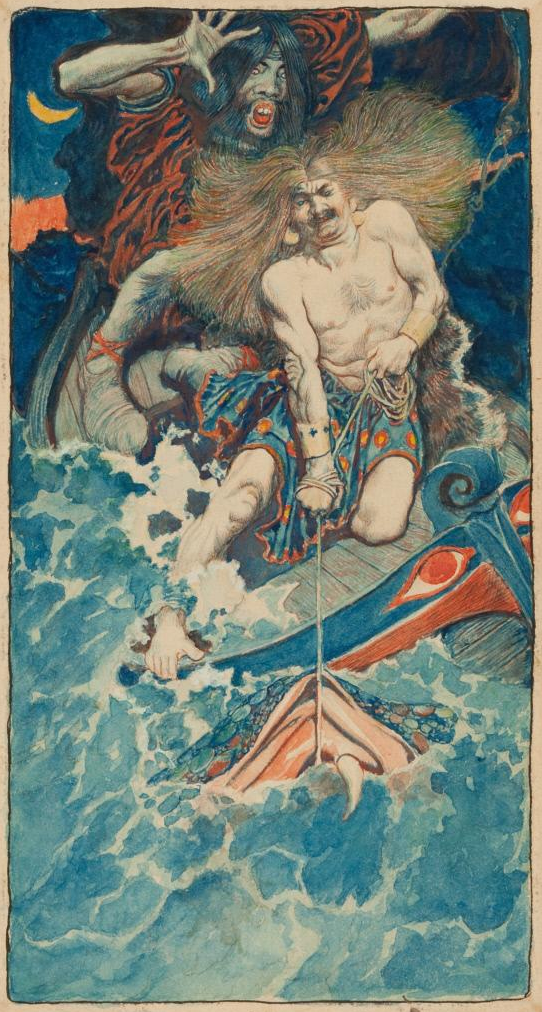

In the Eddic Hymiskviða (“Hymir’s Poem”), the god Thor goes deep-sea fishing for the World Serpent.

He baited his hook

—he who saves men,

sole slayer of the serpent—

with the ox’s head.

Wide open to the bait gaped

the one the gods abhor—

the encircler from below

of every land.Daringly Þórr [Thor],

dauntless in action, dragged

the venom-bright viper

up at the boat’s side.

With his hammer he crushed

the most hideous high hill

of the hair-parting

of the wolf’s welded brother from above.Hone-wreckers sang,

and stony wastes howled.

The ancient earth

all collapsed.

That fish then sank

itself into the sea.

To read these verses literally is to insist that there was once an incarnated divinity named Thor who got in a boat, went fishing with an ox’s head on his line, caught a water-snake so big that it circumscribed the entire earth, and hit it on its hill of hair so hard that the whole planet fell to pieces.

The Fishing of Thor and Hymir by Howard Pyle (1902) [Public Domain]

The bit about the serpent’s hill of hair should be a clue that this shouldn’t be taken literally. That “most hideous high hill of the hair-parting” is a typically riddling Old Icelandic poetic way of saying “head.” It certainly doesn’t mean that the serpent has an elaborately coiffed pompadour.

In a rhetorical style that privileges knotty metaphorical imagery, to read that same imagery literally does what Bruce Lee’s character in Enter the Dragon warns his student against: “It is like a finger pointing away to the moon. Don’t concentrate on the finger or you will miss all that heavenly glory.”

Yes, there is a story happening, for myth is a form of story. Plot is what brings us in, what leads us along the path of time’s arrow. “And then what happened?” asks both the child listening to the bedtime story and the true believer listening to the holy tales of divine deeds.

The danger is to only hear the plot, to only concentrate on the finger. Such a focus almost inescapably fades into fundamentalism as it solidifies the poetic imagery into mundane physicality.

What if we turn from imbibing the plot elements literally to meditating on the moral elements and reflecting on an allegorical reading?

Thor is the one “who saves men,” “sole slayer of the serpent,” and “dauntless in action.” The monster of the seas is “the one the gods abhor,” “venom-bright,” and “the wolf’s welded brother.”

Here we have a solid example of what J.R.R. Tolkien (a deeply religious moralist, writer of allegories, and critic of allegorical writing) addressed in one of his long-ago lectures: “Old Norse poetry aims at seizing a situation, striking a blow that will be remembered, illuminating a moment with a flash of lightning – and tends to concision, weighty packing of the language in sense and form.” In this case, the poet expounds upon a moral concept in the briefest of flashing phrases.

In the poem, Thor serves as a moral exemplar of the individual who is willing to go into harm’s way to help those in need. The descriptive asides in the poem provide meaning behind the myth. To save others, Thor goes alone against the threat and is doughty in deeds. Even when facing paramount peril, he refuses to back down from his duty to serve.

The serpent appears as preeminent example of the threats faced by those living in the world. So rankly unrighteous that he is deeply despised by the (admittedly not purely or naïvely righteous) gods, his glistening poison is clearly visible to all observers, and his close kinship to other harms is obvious, even when they take very different forms. The serpent, then, represents the harmful thing so dangerous that it cannot be explained away or negotiated with, but must be simply and strongly opposed.

Why would we need such examples today?

One answer is that we are so sadly incapable of standing up, Thor-like, to the obvious dangers we are facing together.

There were 34 school shootings in 2021, and there were already nearly 30 by early June of 2022. What is more serpent-like, more clearly abhorrent and “venom-bright” than a shooter strolling into a school to massacre children and their teachers?

There is little disagreement that each such shooting is a horrifying atrocity, yet we are paralyzed.

Sizable numbers of heavily armed and armored officers from multiple branches of law enforcement stood frozen behind ballistic shields in Uvalde as a single teenager continued to shoot students and teachers. Even the fact that some of the victims were family members of the officers did not unroot them or spur them to action.

They had the funding, the manpower, the arms, and the armor. What they did not have was even the tiniest, most minuscule reflection of Thor’s dauntlessness in action. They share this lack with our elected representatives in our nation’s capital.

The bipartisan gun bill that has now cleared initial vote in the Senate has been purged of “any particular limits on an individual’s right to own or purchase a firearm” and “all the Democratic efforts to limit access to guns.” There is no ban on assault weapons (by any nomenclature or definition) and no restriction on high-capacity ammunition magazines.

Instead, the bill focuses on limp support for red flag laws that simply offers grants “to encourage states” to pass such measures, with the caveat that the funds can simply be used for a host of other projects instead. An attempt to close the “boyfriend loophole” relating to domestic violence is countered by restoring the right of abusers to purchase guns without limit if they behave for a period of five years. There are similar couplings of cash grants and baby steps regarding under-21 gun buyers, mental health care, and school security.

Even still, most Senate Republicans opposed the bill and claimed it “infringed on the rights of gun owners.”

Apparently, we as a nation lack the basic fortitude to face down the serpent spitting venom into our eyes.

“A man is like that”

The god Odin speaks of arms in Hávamál (“Sayings of the High One”), the longest single work within the Poetic Edda:

Not a footstep from his weapons

must a man wander

over open land.

For one does not know at all,

out on the ways,

when that man will be wanting his spear.

Here, it seems, is a verse that the today’s literalists can celebrate as divine endorsement of open carry.

Not so fast. Just one verse earlier, Odin uses an idiom not too difficult for modern readers to understand:

Bleeding is the heart

of one who must beg

a morsel for himself every mealtime.

This doesn’t mean that blood is literally gushing from an open chest wound. Even young readers can understand that this is organic imagery meant to evoke feelings of embarrassment and shame.

Odin from The Story of Europe by Samuel Bannister Harding and Margaret Snodgrass (1912) [Public Domain]

A dozen verses later, Odin talks about a tree:

A young fir-tree shrivels

that stands on stony ground,

no bark nor pine-needle protects it.

A man is like that

whom nobody loves—

how is he to live long?

The verse isn’t really about trees. The first half describes the vehicle of the metaphor, the second half reveals the tenor. This isn’t complicated, and it again shows that this poem – quelle surprise! – uses poetic imagery to make its points about proper behavior and right relationships.

For segments of American Heathenry that overlap with the pro-gun movement, Odin’s advice about carrying weapons is tempting to take literally and buffer with appeals to the brutality of the Viking Age, the importance of specific weapons in the mythology, “the violence inherent in the system,” and so on.

Heathens outside of the United States have told me that they read the verse metaphorically, with “weapons” standing for helpful wisdom, knowledge, education, and preparation that protects the individual leaving the house, going out into the world, and facing life’s challenges. It is a verse, they say, about tending to the sharpness of one’s wits, not one’s sword.

Odin is a god known for speaking in verse and in riddles. Among his names and titles in the poetic and mythological corpus are Clever, Deceiver, Double, Masked, and Riddler. With such a figure, should we insist on literal readings of his sayings or ponder masked meanings?

If we do consider these Old Icelandic poems to be key to our religious lives – and I do – it’s important to read them with our critical faculties engaged, to understand that a bleeding heart isn’t always a bleeding heart, a fir-tree isn’t always a fir-tree, and a weapon isn’t always a weapon – especially when Odin the Contrary Advisor is giving us counsel.

Indeed, the honing of critical faculties is a key focus of Hávamál, with numerous verses emphasizing wise choices over foolish ones, observational clarity over emotional reaction, and moderation over overindulgence. Consideration of evidence presented and the taking of judicious action are repeatedly stressed.

Still, when faced with the ever-growing pile of bloody corpses of small schoolchildren whose tiny bodies are riddled with bullet holes, we fuss over language and definitions, we agonize and compromise, we shake our fists and drag our feet. We see the blood on the schoolhouse walls, and we applaud eviscerated half-measures like the latest bill rather than demand needful and fundamental change.

If we can’t read Odin’s shifty verses except at the literal level, how are we to read something as hard to pin down as this?

Do we focus on “well regulated,” “Militia,” “the security of a free State,” “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms,” or “shall not be infringed”? There is endlessly heated argument over emphasis and meaning, with everyone from Supreme Court justices to anonymous Twitter reply guys offering their personal interpretation as definitive expertise.

The liquidity of this single sentence was apparent this week, as the Supreme Court struck down New York’s legal limits on concealed carry of firearms. Justice Clarence Thomas took space in his majority opinion to deride the very idea that recent mass shootings have any relevance whatsoever to the discussion of gun laws. Salon writer Mark Joseph Stern emphasizes that Thomas “suggests that judges may NOT consider empirical evidence about the dangers posed by firearms when evaluating gun control laws.”

The Supreme Court has done more than simply evaluate gun control laws; it has steamrolled them. “Clarence Thomas’ opinion for the court,” writes Stern, “dramatically expands the scope of the Second Amendment, blasting past ostensible restrictions laid out in Heller to establish a new test that will render many, many more gun control laws unconstitutional.”

The physical evidence of dead schoolchildren is irrelevant, according to Justice Thomas. All that matters is the sanctity of that one convoluted sentence adopted as an amendment 231 years ago, when slavery was central to the American way of life, African Americans couldn’t vote, Native Americans couldn’t vote, and women of any ethnicity or race couldn’t vote.

“A vast majority”

As a practitioner of Ásatrú, I understand that Hávamál is likely a collation of several shorter poems by various poets. I don’t believe that Odin himself manifested on this plane of reality and whispered through his beard to dictate the verses into the ear of an entranced poet. I realize that there are difficulties of translation and interpretation with the poem, and I know that translators and scholars can each come to very different conclusions about the same lines from the surviving manuscript.

I also understand that ancient religious poetry is different from modern law.

We can’t add to the verses of Hávamál. We can make eccentric choices of translation that lead to intensely idiosyncratic readings, and we can write new verses in similar style, but what we have created is some new thing that may be inspired by the old poem but no longer is the old poem.

Here in the United States, however, we have a clear mechanism to amend the Constitution. Even with all the willful exclusivism of the Founding Fathers, they left a way for us to not only bring new ideas into the Constitution but also to amend the amendments.

When the opinion written by an unelected judge backed by five other unelected judges is enough to make major changes to the writing and enforcement of gun laws throughout this enormous nation, what is the weight of the will of the people? According to a Vox summary of recent nationwide polling,

A vast majority of Americans supports universal background checks, keeping people with serious mental health issues from buying guns, bans on assault-style weapons and high-capacity magazines, and so-called “red flag laws” that would allow police and family members to seek court orders to temporarily take guns away from those considered a risk to themselves and others. A majority of Americans, of both political parties, oppose carrying concealed weapons without a permit.

The nation’s highest judges are going directly against the will of the citizenry. The elected officials who vet the unelected Supreme Court justices have themselves been bought by the NRA. It’s past time to evaluate evidence and make real changes. The longer we wait, the more schoolchildren will be buried. What can we, the people, do?

There is a process to repeal an amendment. We’ve used it before, when the amendment creating Prohibition was repealed in 1933 and new language was added to the Constitution. The most recent amendment was ratified in 1992 – an interminable age ago for today’s students, but seemingly yesterday for us old graybeards. Now’s the time to once more take action.

Insisting on Constitutional literalism and amendment literalism goes against the very spirit of the documents themselves. This thing of ours is designed to be changed, to be amended by later generations so that it can continue to address current crises. Modern America bears little resemblance to the colonial enterprise that it was in the 1700s, and our laws must reflect the evolution.

We as a nation continue to change and grow. So must our Constitution. To insist on a sacred and sacrosanct nature of the Second Amendment, to treat this one poorly written line as a holy and inalienable sentence, is to bring a fundamentalist religious mindset to a solidly secular situation set up to be changed as changing times dictate.

As a practitioner of Ásatrú, I deeply value Thor’s willingness to act for the people and Odin’s ability to craft thoughtful and meaningful language. If we have the will, we have the way to write a new amendment that more clearly sets out our relationship with weapons than the messy sentence foisted upon us in 1791.

We must be as “dauntless in action” in our efforts to face down the monster of school shootings as Thor is in his confrontation with the World Serpent. We must sharpen the “weapons” of mental resolve that Odin warns us to keep ever close at hand.

We must have the courage to say it out loud, to speak the path into existence.

We must repeal the Second Amendment.

Note: Hymiskviða and Hávamál translations are from The Poetic Edda Volume III: Mythological Poems II by Ursula Dronke (Oxford University Press, 2011).

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.