As a Gardnerian, I’ve been privileged to listen to some tales about the New Forest Coven, the old British Witches who started it all around the time of our progenitor, Gerald Brousseau Gardner. These have ranged from deeply personal anecdotes to doubtlessly embellished tales of what the old nudist got up to, both in and out of the circle.

The old chestnut about Operation Cone of Power more than once. For those not familiar, there’s an oft-repeated story about a group of British Witches getting together to perform a ritual to repel the Nazi invasion during WWII. The story is maybe based in truth, has been used as the basis for at least one graphic novel, and always consists partially of oral history and partially of fabulism – like most Wiccan stories.

Like most Wiccan stories, it reached me during my early study of the Craft, when I was utterly ready to believe. Part of the reason I was so ready for this one was Disney’s 1971 musical fantasy film, Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

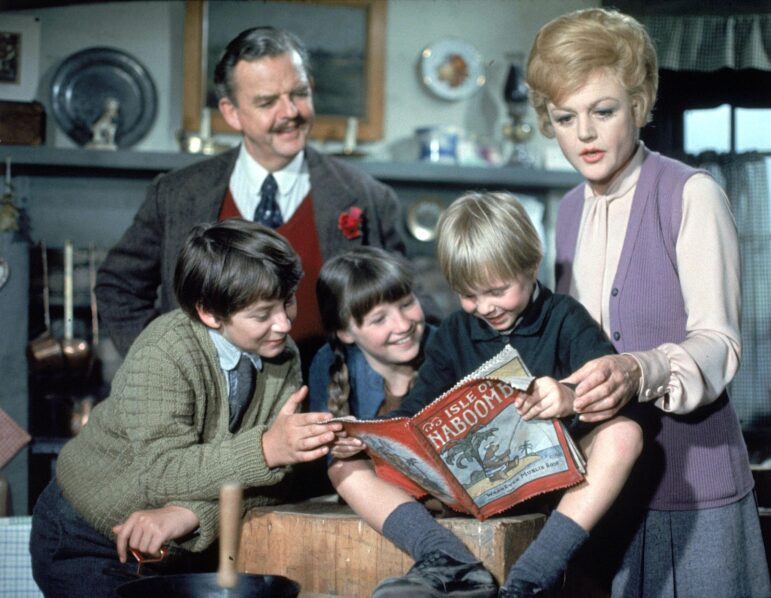

Angela Lansbury as Eglantine Price in Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) [Disney]

Bedknobs and Broomsticks has some features in common with other Disney films a person of my generation might have enjoyed on VHS: capering animated animals who speak and interact with human actors (Mary Poppins), soulful minor-key songs for the introspective proto-goth children in the audience (Robin Hood), and a world of possibilities open to children who have pure hearts and adventurous spirits (Rescuers Down Under, Pete’s Dragon).

It’s different from all of these, however, in two meaningful ways. First, Disney movies did not deal with WWII. Yes, Donald Duck got drafted in 1942 so he could punch Hitler in the face in a delightful piece of period propaganda, but none of their features in the decades following the war dealt with the subject at all. The second is that the Witch is the hero.

The entire plot of this film is about the war, for those of us not utterly entranced by the anthropomorphic football game in the faraway land of Naboombu. Three children come to stay in the countryside with Eglantine Price (Angela Lansbury); they are orphans whose parents died in the London Blitz. They’re greeted in town by the sight of the old Home Guard, a real-life British militia active from 1940-44 and made up of volunteers deemed too senior to serve in the armed forces.

Eglantine, an enterprising solitary using the internet of her time (correspondence courses), is learning Witchcraft specifically to help with the war effort. When the orphans see her mount her broomstick and take to the sky, they decide to stick around rather than high tailing it back to London. When she needs to seek out her long-distance teacher, one Emelius Browne (David Tomlinson), it is because the final and most difficult spell she needs to master has been left out of the grimoire-by-mail he’s been selling her.

David Tomlinson as Emelius Browne in “Bedknobs and Broomsticks” (1971) [Disney]

When I first saw this movie as a kid, I didn’t know what to make of the fact that Browne was a charlatan who was adept at selling fakes and forgeries, and this Witch was only one of his many dupes. It seemed a cruel and unfair thing to do, to sell lies to make money. But it didn’t much matter to me then, because the Hero-Witch was able to make magic out of his chicanery, regardless of its lack of veracity or provenance.

Armed only with some dude’s book of nonsense and her own determination and national pride, Eglantine Price could fly. She could conjure. She could make change. She could twist a bedknob and leave this shabby world of wartime rationing and privation behind to go bobbing along on the bottom of the beautiful briny sea.

Publicity still from Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) [Disney]

Seeing it again as an adult, it moved me in ways I wasn’t prepared for.

Growing up out of the credulous convert phase, I came to understand that most of the stories I had been told about the origins of Wicca are, to put it very kindly, embellished. Like many people who lived before the internet made research instant and easy, I didn’t recognize all the myths I had received about Wicca being ancient, indigenous, matriarchal, a remnant of the Margaret Murray’s made-up witch-cult, or the inheritance for survivors of centuries of European and American witch trials didn’t have evidence behind them. I loved the stories and I wanted them to be true. I didn’t look under the hood until I had been driving this thing for a few years, and I’m sure I’m not unique in that regard.

Now, as I reckon with the humble half-century of history my religion can truthfully offer and the dubious practices of the colonialist practitioners whose initiatory lines lead to me, I find Eglantine Price more relatable than ever. She is sold a bill of goods by some guy who is just trying to get rich and get laid. She trusts the book passed to her by a man she never expects to meet to teach her how to be a Witch alone, and to help her care for the next generation of Witches. (Let’s be real; she’s going to initiate those limey brats.)

And it works.

When this sturdy, determined English Witch gets her hands on the full Book of Shadows that she’s been promised, there is power in it that its purveyor cannot predict. Maybe it’s ancient; maybe it’s realer than he ever was; maybe it’s been nonsense this whole time. What makes the magic real is her will. She applies it, full force, with a true practitioner’s dedication and zeal.

Speaking the magic words, the arms and armor of England’s past rise up like automata to defend their isle from would-be invaders who chose the wrong full moon to cross the channel. Leading an army of spirts, a hero-witch repels the Nazis and helps turn the tide of the war to defend her homeland.

Bedknobs and Broomsticks is a classic work of Pagan cinema for all these reasons. For the Nazi-punching redhead on her broomstick. For the hero Witch who adopts orphans and defends her home with her magic. But most of all, for a practitioner of magic for whom the work is more relevant that who initiated her, who authorized her, who told her how to be a Witch. She does the work, and the magic works. Whether the book she received is divine or whether the man she received it from is honest do not matter at all.

As a Gardnerian, I’ve never seen a movie that was more clearly made for me.

Bedknobs and Broomsticks is available for streaming on Disney+.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.