London’s Wellcome Collection, which has assembled thousands of artifacts and books related to the history of science and especially medicine in an elegant Georgian building on London’s Euston Road not far from King’s Cross Station, is in possession of a remarkable painting made by Robert Bateman in 1870. The Victorian artist hasn’t endured in art history, despite the romantic appraisal made by critic Walter Crane in 1907 that Bateman’s vision encompassed a “magic world of romance… a twilight world of dark mysterious woodlands, haunted streams, meads of deep green starred with burning flowers, veiled in a dim and mystic light.”

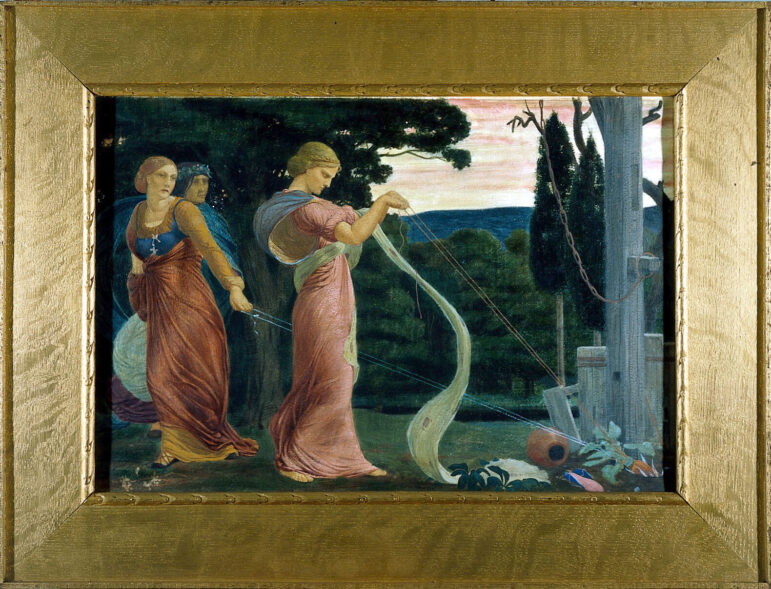

Regardless of Bateman’s posterity, Crane’s description of his corpus is a fair evocation of the painting in the Wellcome’s possession, entitled “Three People Plucking Mandrake.” Bateman’s painting is reminiscent of the starkly neoclassical and oftentimes hermetic work of his 19th-century contemporaries, the Pre-Raphaelites; he has the same fascination with the gloaming period before modernity, the faint squibs of light from that time that endure regardless of the seeming disenchantment of our world. What Bateman depicts are the ways in which ritual can generate not just results, but meaning.

“Three People Plucking Mandrake.” Gouache by Robert Bateman, 1870. [CC 4.0]

In “Three People Plucking Mandrake,” Bateman presents a glowing red dusk at which a trio of women – evocative of Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters – stand near a rough, wooden gallows where an execution has taken place. They use strings to uproot the much-mythologized mandrake root from the soil above which the condemned perished. Identified with a variety of different plants, the man-shaped mandrake was supposedly used in applications from creating a homunculus to producing the ointment necessary for witches to fly. But notably, the three women in Bateman’s painting are not supposed to be witches – they are cunning folk, the indigenous English practitioners of folk magic who existed in uneasy symbiosis within the wider culture of the Middle Ages and early modern period.

As Tabitha Stanmore, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Exeter, writes in her charming and informative Cunning Folk: Life in the Era of Practical Magic, “not every person who practiced magic was considered a witch,” and that in fact many cunningwomen and men were “generally viewed positively by their neighbors.”

What Stanmore offers in Cunning Folk, based in prodigious knowledge and impressive research, is a view into this past world from the 14th through the 17th centuries, when practical magic was an indispensable part of the lives of women and men, deployed to assist in affairs of state and divination of the future, as well as in the finding of lost spoons or the manufacture of fertility tinctures. Based in the scholarly approach that is often called “microhistory,” wherein a scholar examines archival records that were frequently ignored in the past precisely because they focused on the marginalized or dispossessed, Stanmore gives dozens of examples throughout history of actual cunning folk who performed a crucial service for their neighbors that skirted the line between official sanctioned faith and dangerous magic. Throughout her book, Stanmore enumerates the sorts of practical rituals that cunning folk offered in the plying of their trade.

A thief might be discovered, for example, by making suspects eat chunks of cheese in which various charms had been carved, whereupon the guilty party would choke on their morsel. (This must be hard cheese, Stanmore emphasizes.) This was a favored method of the cunning woman Jane Bulkeley of Caernarfon, Wales, in the 16th century. If someone needed assistance in love, there were a variety of love potions that could be whipped up, including the baking of something called “buttocks” or “cockle” bread – the reader can guess at how this recipe worked, though Stanmore explains in detail.

For those in need of medical assistance – and in an era in which the patients of officially sanctioned physicians tended to have a far higher rate of mortality than did those of the cunning folk – there were a multitude of herbal treatments and therapies, such as those offered to the minor poet and courtier Ferdinando Stanley in 1594 when he was suffering from some sort of fevered illness. The nameless cunning woman whose care he was in was condescendingly described by contemporaries as a “homely woman, about the age of fiftie yeeres.” But notably his condition didn’t worsen until he was treated by royal doctors, trained in the now dismissed intricacies of humoral theory.

Cover to “Cunning Folk: Life in the Era of Practical Magic” by Tabitha Stanmore [Bloomsbury]

Cunning Folk is a sterling example of the ways in which a scholar can share the fruits of their research in an accessible (and enjoyable!) manner. Throughout the book, Stanmore’s perspective is refreshingly expansive and tolerant, understanding these centuries on their own terms and never ignoring the fact that practical magic was always intimately human, based in our desires and fears as they relate to our livelihoods, our loves, our health, our family, our future. “To the pre-modern mind,” she writes, “magic was a rational part of the supernatural universe in which they lived… it made perfect sense that men and women – rich and poor, high-born and low-born – would try to harness the powers around them.”

For those living today who make magic a part of their own spiritual practice, Cunning Folk provides a litany of dozens of detailed practices, rituals, conjurations, and incantations with a venerable history back unto the Middle Ages, but in a broader sense Stanmore has an important argument to make about how the work of the cunning folk provides lessons for those of any religious background (or indeed for those with none at all).

Describing an informal experiment in which she asked her friends on social media about the importance of magic in their own lives, Stanmore writes that “When I defined magic in its broadest possible sense – performing actions that, through intangible means, affect the world around us – almost everyone conceded that they had practiced magic at some point.” She concludes that “our lives are not so different from those of our medieval ancestors that we can easily leave magic behind.”

Reading through the assembled brief of Cunning Folk, what becomes clear is that magic had a crucial role even beyond its practical applications, and that was to impart a sense of collective meaning and individual agency, qualities which we remain in particular need of today.

Cunning Folk: Life in the Era of Practical Magic by Tabitha Stanmore is set to be published by Bloomsbury on May 28th. The book may be pre-ordered from the publisher here.

Ed Simon is the Executive Director of Belt Media Collaborative and the Editor-in-Chief for Belt Magazine, as well as being a monthly columnist for both 3 Quarks Daily and LitHub. Simon is the author of over a dozen books, including Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology, Elysium: An Illustrated History of Angelology from Abrams, Heaven, Hell and Paradise Lost from Ig Publishing, and Relic from Bloomsbury. Currently, he is finishing, among other projects, the first full cultural history of the Faust legend for Melville House Publishing

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.