“You may want to consider relocating to an area with adequate law enforcement services.”

This was Sheriff Gil Gilbertson’s advice to women fearing domestic violence in Josephine County, Oregon in the spring of 2012, after drastic cuts to public safety funding resulted in a reduction from 24 sheriff’s deputies to only 6. A few months later, Gilbertson’s chilling warning became a reality when a woman in Josephine County was sexually assaulted by an abusive ex-boyfriend despite calling 911 and pleading for help to the dispatcher for over ten minutes. The dispatcher was not able to send help because there were no deputies on duty at the time. When the Josephine County dispatcher routed the call through to the Oregon State Police, there were also no officers available. Over the course of the call, the State Police dispatcher remarked that it was “unfortunate you guys don’t have any law enforcement up there” and suggested that the terrified caller “ask him to go away”.

The incident made national news a few months later after Josephine County voters once again considered and then narrowly rejected a modest property tax levy that would have provided for adequate law enforcement. Despite having the lowest property taxes of any county in Oregon, and despite the fact that the failure to pass a tax levy the year before resulted in a woman being brutalized, voters had apparently decided that the safety of local citizens was not worth an average of $18.50 per household per month.

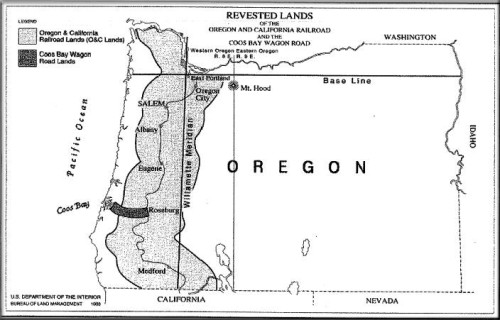

On the surface, it would seem easy to simply blame Josephine County voters for their woes, but the situation that led to the county’s financial crisis is far more complicated than just a matter of property taxes. Nearly 70% of the land in Josephine County is owned by the federal government, and the county receives no tax revenue from that land regardless of whether a tax levy is passed or not. Josephine County is one of eighteen counties in Oregon that has been receiving timber payments from the federal government to compensate for the lost tax revenue from federally-owned land since the 1930s. The amounts of payments are dependent on sustainable-yield harvests, and for many of these counties, known collectively as the “O&C counties”, these timber payments have made the difference between feast and famine for nearly a century. And while the O&C counties prospered as a result of these payments up through the late 1980s, over the past 25 years many of these counties have fallen into financial ruin as the payments slowly dried up.

While many felt that Josephine County voters were simply prioritizing their anti-tax sentiment over their need for adequate public safety services, its important to recognize that in rejecting the tax levies, the citizens of Josephine County were not only demonstrating their belief that the federal government has an obligation to help fill their budget gap, but many also strongly believed that rejecting the levies would either prompt Congress to increase timber harvests or would trigger additional financial assistance from the federal government.

The short explanation behind Josephine County’s financial crisis is that the rapid deforestation of Oregon’s old-growth forests over the past century eventually led to a steady decline in timber harvests, which in turn reduced the federal timber payments down to a trickle. The larger story behind that simple explanation, however, of how and why Oregon developed such a pathological dependence on timber in the first place and why basic municipal infrastructures are so rapidly failing as a consequence of that dependence, is an interesting tale of money and politics that stretches back over 150 years. And while critics had pointed out for many years that Oregon’s failure to diversify its timber-dependent economy would eventually lead to both economic and biological disaster, few ever truly imagined a day where in the words of a local forest activist, “we are now being told that protecting women from rape is contingent upon raping the earth.”

Clear-cut forests near Eugene, Oregon. Photo by Calibas.

It all started with the desire for a railroad.

The Oregon and California Railroad Act, passed by Congress in 1866, dedicated nearly four million acres of land to be made available to any company who would build a railroad from Portland to San Francisco. The Act dictated that the land was to be distributed in 12,800-acre land grants for each mile of track that was built, with an amendment three years later requiring the railroad company to sell the land adjacent to the rail line in 160-acre parcels to be priced at only $2.50 an acre in order to encourage settlement along the corridor. The theory behind the land-grant arrangement was that the sale of the parcels granted to the railroad company would financially compensate the railroad company for building the railroad in the first place. Meanwhile, the value of the government parcels would increase significantly over time due to the building of the railroad as well as the development that would occur on the parcels that the railroad sold to settlers, which would financially benefit the government in the long-term. Similar land grants had successfully enticed railroad companies to construct what became the first transcontinental railroad, which broke ground in 1863 and was completed in 1869.

The O&C parcels were laid out in a checkerboard pattern, extending twenty miles out from each side of the tracks, with the parcels designated for settlers alternating with parcels that were retained by the federal government. Construction was first started in Portland in 1868, and the route was completed over Siskiyou Summit into California by 1877, at which time the Southern Pacific Railroad took control of the railroad line. But while the laying of the tracks itself went smoothly, selling the available land parcels to settlers proved to be quite problematic. The terrain, which was rugged, mountainous, and consisted mostly of old-growth Douglas Fir and Western Hemlock, was not ideal nor practical for development, and the land proved to be difficult if not impossible to sell to potential homesteaders. Timber companies, on the other hand, coveted the parcels, but the land grant stipulated that the land was to only be sold to bona-fide settlers. This left the railroad company unable to recoup the money that was spent on building the railroad, as was the original purpose of the land grant.

And from this dilemma, a massive land-fraud scandal was born.

The racket was brilliantly simple. The president of the Southern Pacific Railroad hired a former surveyor tasked with rounding up working-class folks from the bars and saloons on Portland’s waterfront. The surveyor would escort the saloon patrons over to the land office and pay them to pose as a settlers, where they would register and pay $2.50 an acre for an O&C parcel and then immediately sell the parcel back to the railroad company. The railroad company then sold off the parcels in large blocks to the highest-bidding timber companies, who then harvested the timber without restrictions. This continued throughout the first decade of the 20th Century, until a disgruntled lumber employee tipped a Portland newspaper off to the scheme. The investigations that followed led to hundreds of federal indictments.

After the subsequent trials and convictions, the question remained as to how to legally handle the issue of the land fraud and the parcels themselves. A flurry of lawsuits between the state of Oregon, the federal government, and Southern Pacific resulted in a 1915 Supreme Court ruling that found that although the railroad company had violated the terms of the grant, they had a right to retain the land because the railroad had still been built as per the agreement. A year later, Congress overrode the Supreme Court’s decision with the passing of the Chamberlain-Ferris Act, which declared that 2,800,000 acres out of the nearly four million acres granted were to be revested back to the United States under the control of the General Land Office, which later became the Bureau of Land Management. Under the Act, the land became known as the “Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands”, commonly referred to thereafter as the “O&C Lands”. The original plan under the Chamberlain-Ferris Act was for the land to again be re-sold into private ownership so that the counties could recover their tax base, but once again selling the land to settlers and developers proved to be difficult if not impossible due to the rugged terrain.

Finally, in 1937, Congress passed the O&C Act, revising the terms of the Chamberlain-Ferris Act and mandating that the land be managed for forest production and that the 18 affected Oregon counties be compensated for the loss of tax revenue. The Act guaranteed the counties 75% of the revenue from timber sales on O&C lands, which could be used by the counties for any purpose they chose. A year after the Act was passed, Oregon surpassed the state of Washington as the number-one timber producing state in America.

Under the terms and financial structure of the O&C Act, the counties themselves became the most vocal champions of timber production. More production meant more money flowing into county coffers, and for the next fifty years, the O&C counties in Oregon produced more timber than any other region in the entire world, leveling over 80% of Oregon’s old-growth forests in the process. Between the jobs created through the timber industry and the revenue that flowed through the O&C counties as a result, timber was not only the most dominating economic force throughout Oregon, in many rural areas it was pretty much the only economic force. At the height of the timber boom in the 1940s and 1950s, loggers harvested several billion board feet per year from the O&C lands, and by the 1960s more timber was being harvested on federal lands than any private land in Oregon.

Clearcuts on O&C lands outside of Oakridge, Oregon

For years, as old growth was logged and the O&C counties flourished, environmentalists watched the massive deforestation and subsequent destruction of a thriving ecosystem with horror. Under the terms of the O&C Act, however, there was little they could do to halt the logging. Years’ worth of environmental lawsuits had failed to produce any results, and yet the effects of deforestation on certain species were becoming plainly apparent. In 1986, environmentalists first petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the Northern Spotted Owl as a threatened species. The USFWS reviewed the petition in both 1987 and 1989, but declined to list the owl as endangered. In the meantime, forest activists started to blockade federal forests in order to stall logging operations while more lawsuits worked their way through the court system.

The Northern Spotted Owl

Finally, in 1990, the Northern Spotted Owl was listed as an endangered species under the federal Endangered Species Act. Loss of old-growth habitat was listed as the primary threat the owl, which gave environmental activists the ammunition they needed. A lawsuit was filed, claiming that logging timber harvesting old-growth habitat was in violation of the Endangered Species Act due to the presence of the Northern Spotted Owl, and in 1991 logging was halted on the O&C lands via court order. This order provided immediate relief for the owl and the forest, but also had an immediate and devastating affect on the timber payments that the O&C counties relied on, and officials stated that anywhere from 30,000 to 150,000 jobs would be lost as a result of the court order.

During his first campaign for office, presidential hopeful Bill Clinton promised Oregon voters that if elected, he would work to break the deadlock. Clinton kept his promise, and in 1994 his administration adopted the Northwest Forest Plan (NFP), which was intended to balance the need for logging on federal lands with the need to protect the habitat of the Northern Spotted Owl. The plan strongly decreased the amount of timber yields that were allowed under the original O&C Act, and set aside several million acres of old-growth forest as habitat for the Northwest Spotted Owl. And while the compromise set forth in the Northwest Forest Plan was arguably better than the stalemate that had preceded it, neither side was happy with the results. Environmentalists and forest activists pointed out that the plan did not go far enough to protect old-growth forests and municipal watersheds, while timber executives and county officials insisted that the allowed yields were not high enough to sustain the timber industry and the economic health of the O&C counties. Over the next several years, the concerns of both groups came to fruition. Environmentalists witnessed, documented, and publicized the negative effects that the logging was having on the ecosystem, which further empowered the forest defense movement to take up blockades in the forest. Meanwhile, the timber revenues of the O&C Counties continued to plummet, and timber jobs steadily started to vanish. Rural towns descended into poverty, while municipal and county governments struggled to stay afloat.

Once again the O&C dilemma compelled the federal government to act, and in the year 2000 Congress created a safety net for the Oregon timber counties as well as other rural areas affected by declining timber harvests by enacting the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000. The Act allowed the O&C counties to receive the average of the three highest timber payments from 1986 through 1999 in lieu of the payments owed based on actual yields, which at the time was an average of only 150 million board feet a year. The Act originally was set to expire in 1996, but was renewed several times without lapsing, with the amounts decreasing with each renewal. In early 2012, however, the bill stalled in Congress and the federal timber payments lapsed for the first time since they began in 1937, which directly resulted in Josephine County’s drastic public safety cuts and Sheriff Gil Gilbertson’s ominous warning. Although Congress eventually renewed the payments, the Act is again set to expire in a few years.

Today, only 10% of Oregon’s old-growth forests remain, and two more “compromise” bills working their way through Congress are being championed as problem-solvers but also potentially threaten much of the remaining old-growth habitat. The competing bills, one sponsored by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and the other sponsored by Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), have both come under fire from environmentalists and forest activists for increasing timber harvests on the O&C lands. DeFazio’s plan would turn over portions of the O&C lands to a state-managed trust for harvest, while granting federal wilderness protections to other sections of the O&C lands. Wyden’s plan is strikingly similar, claiming that it will boost timber harvests from the current 150 million board feet a year to anywhere between 300 and 400 million board feet a year while protecting trees that are over 150 years old. It is inevitable that one of the bills will become law, which in the long run will only serve as another band-aid that will not satisfy either side. The potential agreement only furthers Oregon’s dependence on a finite resource that is undeniably running out.

Forest defenders blockading threatened old-growth habitat

Growing up on the other side of the country, it was my fascination with the forest defense movement in the Pacific Northwest that first lured me to Oregon a decade ago, where I spent two weeks in the Willamette National Forest assisting with a tree-sit at a timber sale on the O&C lands. At the time, I knew little of the history and politics that led to the action I was participating in, but the experience of climbing 200 feet up a Douglas fir and the effects of sleeping and waking surrounded by old-growth had forever altered my understanding of the sacred. It was also in the forest that I first regarded the actions of forest activists as a militant form of earth-worship, and it was the energy and passion of certain individuals within that movement that strongly factored in my decision to permanently relocate to Oregon a few years later. Since then, my experiences with the land and the people here have greatly expanded my understanding of the timber-related history and politics that have driven and controlled this area for the past century. Never have I seen or experienced a single issue that so strongly reverberates through so many people and so deeply within a place, and never have I been at more at a loss for answers or solutions. Often I can’t help but feel that Western Oregon is a real-life version of “The Lorax”, complete with an equally grim and predictable ending.

In the meantime, it was announced last week that petitioners in Josephine County have gathered enough signatures to place another tax levy on the ballot this coming May. And while I can’t predict exactly what the future holds for Josephine County or any of the other O&C counties for that matter, what I do know for sure is if the long-term safety, security, and livelihood of the citizenry is dependent on the consumption and destruction of our old-growth forests, we will have retained neither our security nor our biodiversity in the end.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

A brilliant demonstration of the environmentalist adage, “You can’t do just one thing.”

Alley, thank you so much for this wonderful exploration of a complicated history. I often think that it is our failure to see the world in terms of large, integrated systems that has brought us to the brink of social and environmental collapse. If only we could learn to see the whole picture as clearly as you’ve laid it out here, in terms of history, ecology, economy, and society, I suspect we’d be a lot farther along in solving the problems that confront us modern humans.

I know this kind of integrated analysis asks a lot of readers (and writers–thank you!). But your writing something so clear and complete encourages my hopes.

We have got to learn to see holistically before it is too late!

Wow. Damn, its amazing how you nailed the essence of this story, and I say that as the son of an Oregon timberman.

Courtesy post: I posted a link to this article on a Rod Dreher blog post at The American Conservative. Dreher’s post focuses on the law enforcement aspect without exploring much else, and your article here might offer TAC readers a closer perspective on the situation.

Brava.

Thanks for pointing me to the Dreher article. Interesting that his came out just yesterday. One of the reasons I was motivated to write this in the first place was due to the numerous pieces I’ve read over the past year or so that focused on the issue without ever going into the history. Other articles briefly touched on the O&C history, but left huge chunks of the story out. Somewhere on the State of Oregon’s website is an interesting piece which has lots of historical details but left the entire land fraud issue out completely. If you’re going to tell a story, get it right dammit!

I’ve known Dreher for a while, and became personally acquainted with him while he lived in Philly. He’s a journalist of the old school, sort of, and while he may not express it I expect him to take a look.

I would expect that he will. He is a lot more open minded than he would ever care to admit.

Thank you for this eye-opening, well-researched, evocative, beautifully written piece.

An acquaintance of mine once described the Pacific Northwest as having “introspective weather and primal forests.” My feelings exactly.

The primal forests are what ultimately made me a Pagan. When I first moved to Oregon in 1992, I fell in love with the amazing trees here, and this experience forever altered my understanding of the sacred. I have wondered about the true history and politics underlying the logging controversies ever since.

The problems you identify here are systemic, I think, and need to be addressed accordingly. Have you read Charles Eisenstein’s book “Sacred Economics?” It is brilliant, and appreciated by many Pagans for good reason. More than any other book I’ve read, it has given me real hope that changes can be made to our money system such that it rewards rebuilding and preservation of the ecological commons, instead of rewarding ecological destruction, as it currently does.

Thank you! I haven’t read Eisenstein’s book, but its been mentioned to me before, so I suppose I’ll hunt it down….

Hmm–if the age standard is really honored in the harvest plan, then the bills may not be that bad. Doug Fir, while providing incredible old-growth ecosystems in mature populations, is also sort of a weed. That’s why our predecessors here used to burn it back every few generations. In its firs century and a half, Doug Fir actually reduces biodiversity by shading out other species.

Of course, after a century and a half of logging and replanting, it really is time for all logging to be confined to second growth.

Wonderfully written and very informative. I love the way you show how we are all a part of the environment and its concerns by bringing in the lack of protection for an abused woman in the beginning.

One thing- I still have to say that the spotted owl was not as endangered in reality as it was on paper, and that it was the Timber Graders greed (most of them) that led to the owls ommission in their observation books, and hence, started the controversy though the suggestion that there was a severe impact on them. A different kind of fraud on their part, as it were.

Great article. I’m curious, though – the county I live in in Colorado is 80% public land & we get “payments in lieu of taxes” from the federal government to make up for the fact that all that land is not on the property tax rolls. For other reasons (ski area) our county is pretty prosperous, but I know the “PILT” payments are important to the county budget. Don’t they get those in Oregon?

No, payments in the O&C counties have always been based on the percentage of receipts from timber harvests. Since 2000, they’ve received payments based on former yields, not the actual yields, but they were still always tied to timber profits. The O&C payments were in place long before the current PILT system was conceived of. If Oregon got PILT payments, we wouldn’t have this issue and so many wouldn’t be chomping at the bit to cut down the rest of the old-growth. I’m pretty sure that the specifics within either the original O&C Act and/or the Northwest Forest Plan pre-empt Oregon’s ability to qualify for PILT.