It’s almost Valentine’s Day, and Lupercalia has nothing to do with it. So we’ll cover both.

Lupercalia by Andrea Camassei c. 1635, oil on Canvas. Museo del Prado

Historians tend to be cautious when it comes to saints’ lives, and factual precision has never been the defining feature of medieval hagiography. When it comes to St. Valentine, the historical record is thin, contradictory, and far from romantic. The stories that circulate today, secret weddings, defiance of emperors, love notes signed “from your Valentine,” are really late embellishments layered over fragmentary accounts.

Even the identity of St. Valentine remains uncertain. Some traditions speak of a single priest, or bishop, martyred in Rome in the third century. Others suggest there may have been two – or possibly even four- different men named Valentine whose stories merged over time.

What they appear to have shared was not a flair for romance but a beheading, not a very candlelit dinner and heart-shaped chocolate type of event.

The earliest known association between St. Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears not in church records but in literature. Geoffrey Chaucer, often called the Father of English Literature, made the connection in his late 14th-century poem Parliament of Fowls. In it, he describes St. Valentine’s Day as the moment “when every bird comes there to choose his mate.” That poetic image of birds pairing off in mid-February appears to be the first explicit link between the feast day and courtly love in English writing.

Chaucer’s lines, written in Middle English—“For this was on seynt Volantynys day / Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make”—helped reshape the day’s meaning. Rather than rooting the holiday in Roman fertility rites, as is sometimes claimed, it was medieval poetry that gradually nudged Valentine’s Day toward romance. The idea caught on among the literate classes of England and France, where aristocratic courtship rituals were already infused with symbolic gestures and elaborate declarations of affection.

Still, it would take centuries for the holiday to become the commercial juggernaut we recognize today.

A turning point came in the 18th century. A 1784 poem from Gammer Gurton’s Garland gave us one of the most enduring verses in the English language:

“The rose is red, the violet’s blue,

The honey’s sweet, and so are you…”

Simple, rhyming, and easily reproduced, the poem helped standardize the sentimental language that would come to define Valentine’s Day. By the 19th century, advances in printing technology and affordable postage transformed personal notes into mass-produced commodities.

In the 1840s, Esther A. Howland earned the title “Mother of the Valentine” in the United States by producing ornate Valentine’s cards decorated with lace, ribbons, and embossed paper. Her creations offered a domestic alternative to expensive imported European cards and sparked a wave of holiday merchandising on both sides of the Atlantic.

The confectionery industry quickly followed. Cadbury introduced heart-shaped chocolate boxes in the 1860s, helping to cement the now-familiar pairing of sweets and sentiment. In 1866, Daniel Chase—brother of Oliver Chase, founder of the New England Confectionery Company—developed conversation candies stamped with short romantic phrases. Though they did not assume their iconic heart shape until the early 20th century, these sugary messages carved out a lasting niche in the Valentine’s marketplace.

Chocolate empires were rising as well. Milton S. Hershey opened his first candy shop in 1873, eventually founding The Hershey Company in 1894. In 1907, Hershey’s Kisses debuted—small, foil-wrapped confections that would become inseparable from American expressions of affection.

The greeting card industry was not far behind. Hallmark Cards, founded in 1907, entered the Valentine’s market by selling postcards in 1910 before shifting to dedicated Valentine’s cards in 1913. By the mid-20th century, corporations from De Beers diamonds to Coca-Cola were promoting love as both an emotion and a purchasing opportunity.

In the 21st century, Valentine’s Day has evolved into a massive commercial event encompassing jewelry, dining, travel, entertainment, and online promotions. According to annual surveys by the National Retail Federation, Americans now spend billions of dollars each year marking the occasion. For 2026, projected spending on significant others alone was estimated at $29.1 billion—a record-setting figure that underscores how expensive romance seems to be these days.

Yet beneath the advertising campaigns and glittering displays lies a layered history: a martyred saint (or several), medieval poetry about birds, Victorian card-makers, and confectioners eager for a seasonal boost in sales.

Dísablót is a Norse rite devoted to the dísir, the powerful female ancestral spirits and protective beings who guarded families, clans, and communities. The precise timing of the festival has been lost to history. Most sources place it in late winter, but no one can say exactly when it was observed. It may already have passed. It may be unfolding now. The old calendars followed the moon and the land more than fixed dates, and Dísablót likely shifted with the rhythms of season and region.

Medieval Icelandic texts, especially the Ynglinga saga, describe a Dísablót held at Uppsala in Sweden before the coming of spring. Over time, the associated public assembly known as the Disting became fixed near early February, but the original observance almost certainly followed a lunar reckoning rather than a modern calendar.

The dísir were not distant gods removed from daily life. They were intimate presences—ancestral mothers, foremothers, and protective feminine spirits whose influence shaped fate and fortune. They stood close to the living, guardians of lineage and land. Dísablót was a time to honor them, to seek their protection during winter’s harshest stretch, and to ask for blessings as communities approached the fragile threshold of spring.

Dísablót is sometimes compared with Álfablót, another Old Norse sacrificial rite. While Dísablót appears to have been a more public observance, Álfablót was described as private and household-based, often closed to outsiders. If Dísablót honored the collective feminine ancestral powers of a people, Álfablót likely focused on land-spirits or ancestral beings tied to a specific farm or family line. Together, they suggest a spiritual world in which the unseen is composed of ancestors, spirits of place, and protective presences, all remained woven into daily life.

In some regions, sacred observance blended seamlessly with civic life. Dísablót coincided with the Disting, a seasonal gathering that included legal assemblies and trade. The marketplace and the ritual fire existed side by side. This interweaving of spiritual devotion and communal responsibility reflects how deeply the dísir were embedded in everyday existence. They were not abstractions but guardians invoked in matters of survival, prosperity, and kinship.

Themes associated with Dísablót include ancestor veneration, protection during winter’s dangers, household blessings, and the strengthening of communal bonds. In the lean months, when food stores thinned and daylight lingered only briefly, honoring the dísir affirmed continuity. The living remembered that they were part of something larger than a single lifetime.

Dísablót offers a meaningful opportunity to reconnect with ancestral lines, especially the women whose labor, resilience, and wisdom shaped our inheritance. It can be as simple as lighting candles, offering bread or mead, speaking names aloud, or sitting in quiet gratitude.

Spelling The Heka-Tea with Marcus and Evanne

Marcus and Evanne are sharing some amazing podcasting – this week covering Love and more Love as well as Aphrodite, Recipes, Love, Mixology, and possibly more Love.

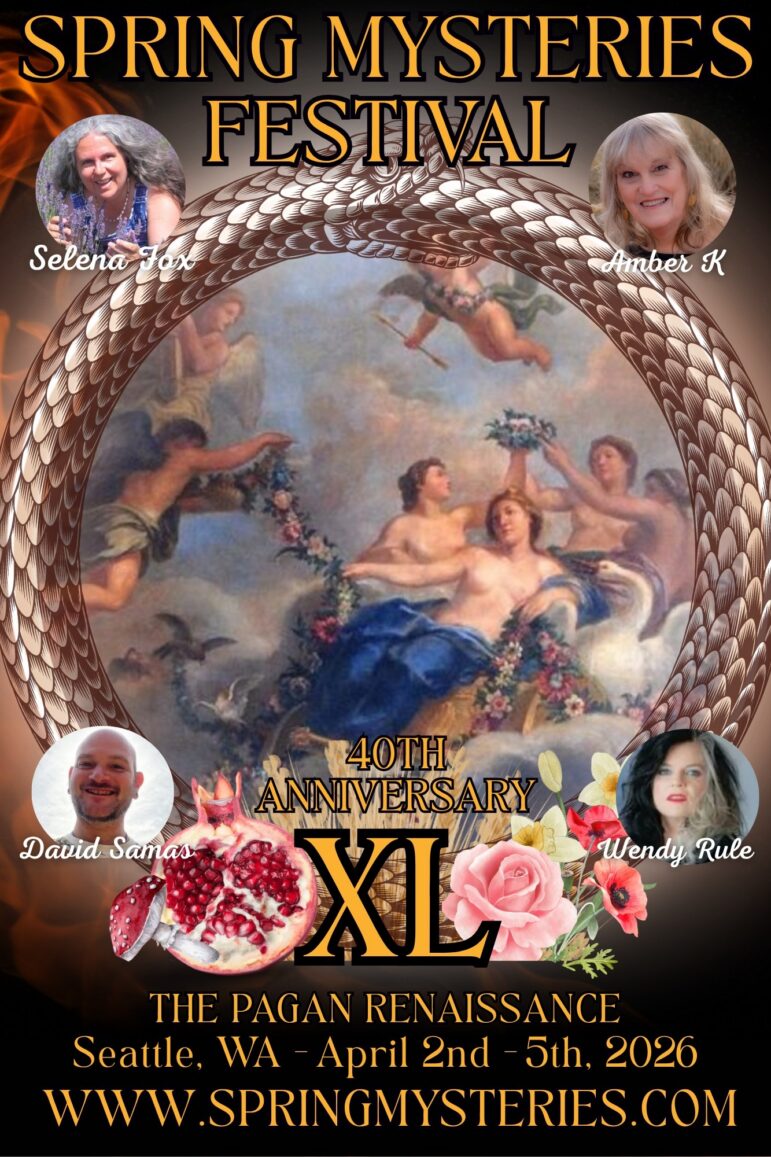

And speaking of Spring Mysteries, here is a quick reminder:

And don’t forget to catch another Amazing episode of Desperate House Witches with Taliesin Govannon and Raina Starr

![]()

There’s a growing conference in Portland! Spirit Northwest is a transformative and new format gathering for seekers, offering long-form immersive workshops on Paganism, witchcraft, and natural magick. Now in its second year, the conference is hosting keynotes from M. Isidora Forest, Laura Dávila, and Ivo Dominguez, Jr.

The conference organizers write, “Immerse yourself into modern and ancient wisdom, workshops, sacred rituals, and spiritual practices that inspire growth and connection.”

Information about the event and how to register is available on their website.

![]()

Events and Announcements

More Events at our new Events Calendar

Tarot of the Week by Star Bustamonte

Deck: Heart & Hands Tarot, by Liz Blackbird, published by U.S. Games Systems, Inc.

Deck: Heart & Hands Tarot, by Liz Blackbird, published by U.S. Games Systems, Inc.

Card: Ace of Cups

The incoming week is apt to elicit feelings of compassion and joy that may even seem overwhelming. Sharing these emotions is likely to open up a gateway within the self that amplifies creativity, generosity, and kindness and inspires the same in others. New beginnings that revolve around conception and birth, or a relationship, are also emphasized. Passion for what both feeds and expands the heart is liable to be an underlying theme.

In contrast, past harms are likely to have created a situation where relationships and feelings for others are held at bay or held at a distance. Denying feelings will not make them cease to exist, but is only more apt to compound already complex feelings. This is a good week to work on self-love and perhaps some radical self-care.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.