Today’s offering comes to us from Gavin Fox, a freelance occult and paranormal author currently residing in Cardiff, South Wales. As to be expected of someone who grew up in London’s East End, Gavin has an eclectic and at times sarcastic view of culture in general, and this thread of gallows humour runs throughout his work. He specialises in creating engaging longform articles on a variety of weird and unusual topics. These include chaos magick, necromancy, ghost hunting, demonolatry, and the unfair treatment of his fellow occultists both past and present. Visit him online at The Accelerated Chaote.

It is human nature to look back fondly on what may once have been, the roads not travelled and potential avenues for acceptance which never quite took hold. Yet this longing for lost futures, while indeed comforting, is pointless if not done honestly. Because no matter how difficult modern Paganism is finding the wider media now, they were rarely treated any better in the past ether. And as will be shown, longing for nebulous claims of a once tolerant mainstream will only allow half forgotten wounds to fester instead.

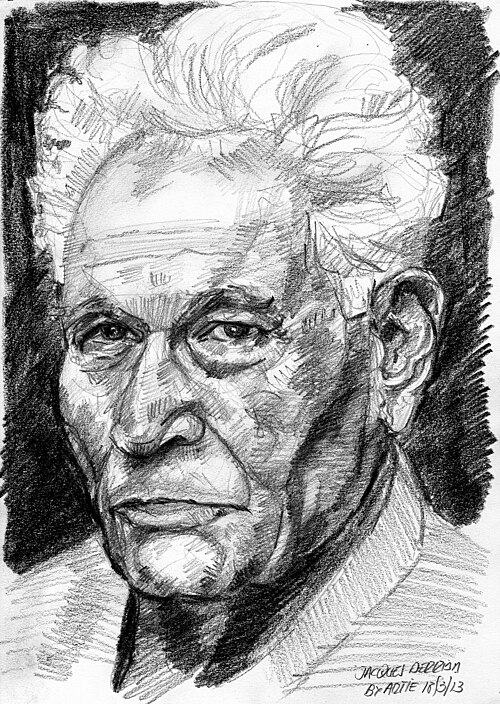

Hauntology is a fascinating concept, one that has grown and mutated as different groups began to work the initially simple idea into their own disparate strands of social critique. Coined by Jacques Derrida, a 20th century philosopher who is best known for his influence on both postmodern and post-structuralist thought, the term first saw print in his 1993 book Spectres of Marx. Used within a purely political framework there, it has since become a more generally accepted tool for understanding the hidden roots of a wide range of topics.

A portrait of Jacques Derrida, who coined the term “hauntology.” [Arturo Espinosa, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

![]()

We know it’s a pain to ask for money—but here are the facts.

Since January, The Wild Hunt’s readership has soared past 400,000 views a month. That’s humbling—but higher reach also means higher costs. Hosting, technology, and reporting all add up.

Our editors are unpaid, and some of our staff volunteer their time. But we believe everyone deserves to be paid for their work.

We tried advertising once, and readers were flooded with Christian ads. That’s not who we are. The Wild Hunt is dedicated to providing Pagan readers perspectives they won’t see anywhere else.

We’ll never hide our stories behind a paywall—our community deserves access, no matter their ability to pay. To keep Pagan news free, independent, and authentic, we rely on you.

A few hundred supporters pledging $10 a month — or more if you can — would keep The Wild Hunt secure for the year. If you’ve been thinking about supporting us, now is the time.

👉 This is how you can help:

Tax-Deductible Donation

PayPal

Patreon

As always, our deepest gratitude to everyone who has brought us this far.

![]()

As a less academic, more pop culture related argument, hauntology states that potential futures never really go away, drifting like spectres in culture’s collective subconscious and influencing the present from the unseen. They lash out from beyond this veil of memory like words caught on the tip of the tongue, colouring the path that people walk despite never finding a foothold to manifest in full. Trends recur, fashions are cyclic. And bigotry already dismissed as too far-fetched to be real may instead manifest directly through its own absence.

The foreshocks of this culture war lie half a century ago. That both Witches and Pagans were increasingly drawing the unwelcome attention of producers who saw them as either sideshow attractions or a dangerously divisive “other” can be inferred from just how poorly they were represented by the American media during the 1970s. The darkest period of the Satanic Panic may have been a decade in the future at this point, but its seeds were germinating around the time both 1973’s The Exorcist and 1976’s The Omen began delivering thrills and chills to a mostly unprepared audience.

The Wicker Man would add a uniquely British flavour to the mix in 1973, cementing a link between Paganism and the growing folk horror subgenre that persists to this day. Of course most films are not factual, despite panicked claims to the contrary by those who seek secret codes within the narrative. While their wider reach within culture is far broader than that of a humble documentary the inherent difference between the perception of something claiming to be fiction and asserting itself as fact is where the potential for long lasting harm lies.

Christopher Lee as Lord Summerisle in Robin Hardy’s “The Wicker Man” (1973) [Studiocanal]

Examples such as The Occult – An Echo from Darkness, which aired in 1970, tended towards bundling those who would now be recognised as Pagans in with less savoury characters from the occult fringes. Opening on self-described ritual magicians talking about their most startling excesses as well as a supposed journalist sitting on the altar stone at Stonehenge while admonishing those who once worshipped there, the end result is an extremely dated looking diatribe that conflates Satanism and Witchcraft in a way that would sadly become the norm during later years.

A far more balanced treatment of both Stonehenge as well as the Druidic community who were drawn there at the time can be found in episode 24 of the first of season of In Search Of, a series hosted by Leonard Nimoy that aired in 1977. The Salem Witch Trials were covered in a later 1980 episode, season five, episode 13. In truth the show barely touches on those historic events though, instead looking at the modern community within the city. This includes interviews with Laurie Cabot, her family, coven, and even highlights some ritual work too.

This episode then is an outlier, a rare example of mainstream made for television content from that decade that offers the Pagan community room to breathe, albeit through the very specific and far from universal lens of practical Witchcraft. That is no surprise, as In Search Of was a show known for treating non-mainstream topics with a level of respect that many similar productions of the time seemed to lack. It can therefore be forgiven for not quite getting the point.

The UK of the 1970s always seemed to be more interested in ghosts and hauntings than actual magic, at least outside of the Witchcraft-obsessed tabloid press of the time. That said, when the BBC decided to throw their hat into the ring with 1971’s The Power of the Witch: Real or Imaginary?, the results were about as terrible as is to be expected from an organisation that prided itself on upholding Protestant, Church of England standards.

Doreen Valiente approaching in a shot from 1971’s THE POWER OF THE WITCH – REAL OR IMAGINARY? [BBC]

A thinly veiled excuse to turn the words of British practitioners against them, reasoned comments by such well respected voices as Doreen Valiente and Eleanor Bone were drowned under a tide of baseless accusation. This diatribe was led by an investigative journalist who, for reasons of public safety, repeatedly doubled down on tall tales of occult crime even when the very witnesses themselves chalked it up to happenstance instead.

Of special note were the lengthy interjections by Cecil Williamson, a man who despite an enduring interest in the occult seemed content to spread literal falsehoods about Witches taking part in modern black magic murder. And he was in good – or rather bad – company. The entire documentary is full of upper class folklorists and authors that talk like they find the whole concept of the Wiccan Old Religion tawdry. It all comes across as if the BBC producers stood in the courtyard of Oxford University and asked if anyone had ever seen a goat in a robe.

As the 1980s dawned, UK paranormal television seems to have taken a back step from trying to engineer Witch-hunts, instead forging ahead into the same territory that In Search Of had explored in the decade before. Good examples of this more rounded approach were Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World from 1980 and the sequel, World of Strange Powers from 1985, both of which covered a laundry list of what would now be termed Fortean topics. Pagan landmarks, such as Avebury and the Cerne Abbas Giant, were explored with a refreshing air of friendly enquiry by researchers who genuinely seem to love what they do.

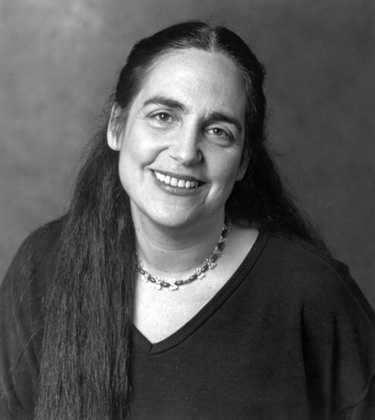

Margot Adler

At the other end of the spectrum is The Occult Experience, a movie length documentary from 1985 that is held in far higher regard than it really deserves. Yes, it boasts classic ritual footage, as well as brief interviews with Margot Adler, Selena Fox, Alex Sanders, and Janet Farrar among others, but the narrative again falls into the all too common trap of presenting both Paganism and Satanism as related currents within the same cosmology. Having so many recognisable faces on display helps to legitimise the wildly incorrect assumptions held by those seeking fresh Witches to burn, and disrespects to the core beliefs of both groups.

If there was an elephant in the room with regards to the media of the period, it would be the presence of The Church of Satan. Indeed, almost all these documentaries at least give Anon LaVey’s group a nod, if not outright reusing the same footage from 1970s Satanis: The Devil’s Mass. Of course it is the rituals from that film which see the most replay, resplendent as they are with dark robes and nude women on altars. This further forges a link between general Witchcraft and inverted Christian symbology in the mind of the uninitiated that does not in truth exist.

Yet the blame does not lie with them. LaVey’s group were expert publicists and revelled in their perhaps deserved notoriety, speaking their truth to a world that was both appalled and fascinated by what they saw. That the Witchcraft community would be swept up in the wake of this likely concerned the average Satanist very little, though that misrepresentation of Pagan ideals lies instead with the documentarians themselves.

Interestingly, American television seems to have refocussed on more general paranormal topics as well as true crime as the decade drew to a close. Starting in 1987, Unsolved Mysteries would become the most popular example of this blending of tall tales and murder reconstruction content. Thankfully it only rarely dipped its spoon in the Satanic Panic spice mix which had flavoured the news cycle since 1983’s now widely debunked McMartin Preschool ritual abuse case.

Aside from opening salvos by Devil obsessed talk show hosts such as Bob Larson and Geraldo Rivera, little changed until the end of the decade, when religious intolerance underwent a democratisation of sorts. Here the shift would be one of origin if not content. The mass adoption of VHS video recorders allowed for a slide away from the large scale production companies that were responsible for earlier documentaries towards low budget attempts filmed by individual churches themselves. Even the most lacklustre research of days gone by gave way to pure fantasy, and the end result was lunacy on film.

The true scale of the tapes produced during that period may never be known; some were limited run and only made available by mail order from church to church. Yet the surviving examples, such as The Edge of Evil and Exposing the Satanic Web, both from 1989, are barely worth the effort to sit through anyway. Little better than sermons intercut with both self-proclaimed ex-Witches and laughably fake law enforcement experts, it offers very little to the wider conversation. At least the hair on display in 1994’s Law Enforcement Guide to Satanic Cults is legendary.

That said, it would be unfair to infer from the previous handful of examples that there was some grand conspiracy to drive all Witches back underground, at least outside of the obvious Satanic Panic content that would go on to dominate the early 1990s. What has been shown is instead the product of a far more organic process, one that stems from a need to push both engagement and social cohesion through morality tales presented as fact. Bums on seats, so to speak, and the audience quietly nodding along as they are told to fear what is different.

That is no excuse, however. Whether an anti-Witch or anti-Pagan documentary’s stance stems from either religious intolerance or social spectacle, the end result is still the same. It is commendable to see the majority of practitioners featured in such tarnished narratives doing so out of a desire to set out the stall for Paganism as both a vibrant and viable reaction to the quickly changing world of the time. But this misguided attempt at setting the record straight also led to their presence in some ways legitimising productions that should have perhaps been avoided.

Ultimately, as has been shown, the Pagan community needs to avoid falling into the trap of looking to the past for friends among the mainstream that were never really there. Yes, neither the future wherein the devil walked down main street on a sunny Sunday afternoon to visit the local church, nor the one where the Wiccan Old Religion supplanted Christianity in the hearts and minds of the general populace, ever came to pass. Witch kings and queens do not rule the UK from their sacred groves, and druids do not own Stonehenge.

The status quo still functions as intended and mainstream religion maintains its market share, despite the number of Witches suffered to live in their midst. But remember, their very absence gives these lost futures power, like hidden traumas they push the cultural narrative in potentially harmful directions, hungry ghosts of half remembered and potentially apocalyptic worlds yet to manifest. So just because those things have never happened does not mean they never could, and for some therein lies a great and terrible fear.

Sources

- Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World. UK: Yorkshire Television, 1980.

- Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers. UK: Yorkshire Television, 1985.

- The Edge of Evil. USA: Word Inc., 1989.

- The Exorcist. USA: Warner Bros, 1973

- Exposing The Satanic Web. USA: Roever Communications, 1989.

- Law Enforcement Guide to Satanic Cults. USA: Gun Video, 1994.

- In Search Of. USA: Alan Landsburg Productions, 1976 – 1982.

- The Occult – An Echo from Darkness. USA: ECRF Production, 1970.

- The Occult Experience. Australia: Cinetel Productions Ltd., 1985.

- The Omen. USA: Twentieth Century Fox, 1976.

- The Power of the Witch: Real or Imaginary?. UK: BBC, 1971.

- Satanis: The Devil’s Mass. USA: Execution Style Entertainment, 1970.

- Unsolved Mysteries. USA: Cosgrove/Meurer Productions, 1987 – 2010.

- The Wicker Man. UK: British Lion Films, 1973.

![]()

![]()

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.