Stefano Ciotti contributed to this article

BARI, Italy – Research published last month by a team of archeologists from England, France, and Italy asked two questions and reported their findings in the European Journal of Archaeology: “Who becomes an ancestor? What do ancestors do?” This study explores how ancestors were created in this particular village throughout a couple of centuries—a period that may correspond to the lifespan of oral histories within the community.

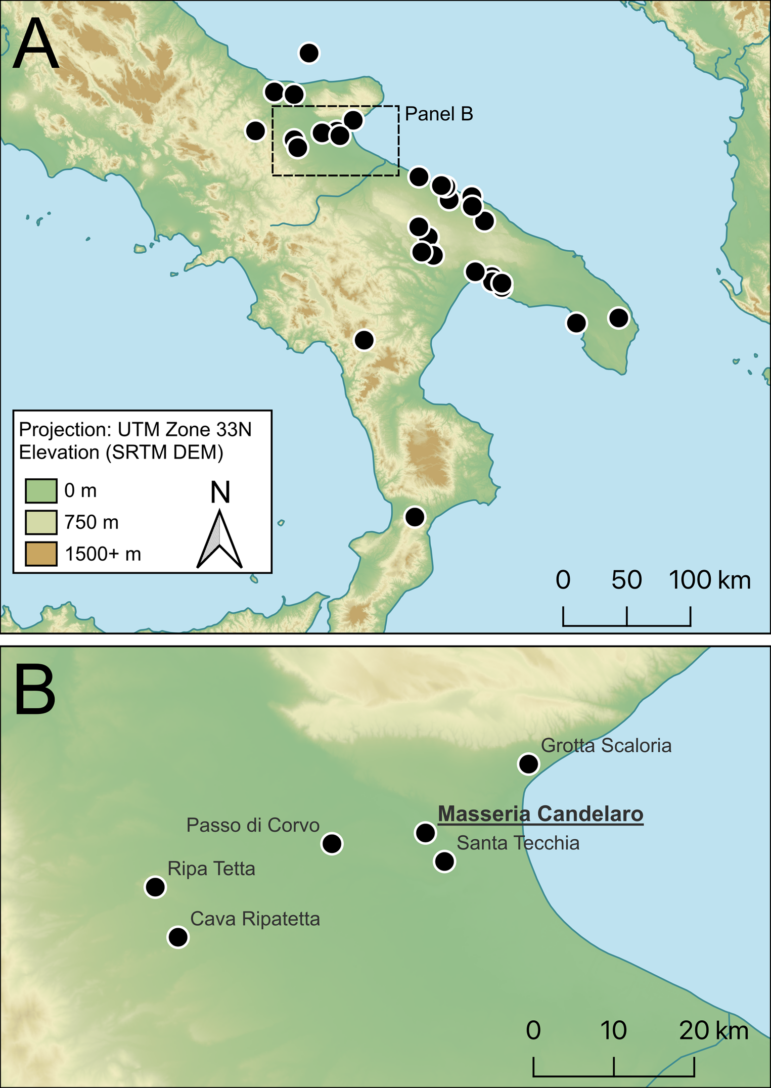

The researchers working at Masseria Candelaro, a Neolithic village in Puglia, Italy (the famous heel of the boot) discovered a collection of 15 human skulls in about 400 fragments purposefully placed on the top of a disused area. The discovery offers a rare insight into the ritualistic and symbolic importance of human remains in Stone Age societies, specifically how and why the deceased remained as ancestors.

Cliffs in Puglia [Pixabay

The researchers noted that Ancestors are not simply born—they are made. The rituals dedicated to ancestors differ significantly from standard funerary rites. While they reference the past, ancestral rituals are inherently forward-looking, connecting the ancestors to contemporary socio-political concerns, legitimizing traditions through continuity, and calling for action in the present.

The transformation of a deceased person into an ancestor is often achieved by altering their physical remains. Practices such as secondary burials or the curation of selected bones extend the memory of the deceased and provide tangible links to their legacy.

The skulls, predominantly male, were discovered in a pile within a sunken area identified as “Structure Q,” which was not designed as a cemetery. Instead, this structure featured alternating layers of domestic and ritual artifacts, suggesting it served as a multifunctional space later adapted for ceremonial use. Radiocarbon dating places the fragments between 5618 and 5335 BCE, indicating they were collected and utilized over nearly three centuries, spanning six to eight generations.

The fragments showed no evidence of cut marks, violence, or healed trauma, ruling out their use as war trophies or the remains of individuals who met violent ends or cannibalism.

The pattern of fractures suggests the skulls were retrieved from burial sites and deliberately handled as part of long-standing ancestor rituals. Lead author and bioarchaeologist Michael Thompson noted: “Human bone had a specific kind of meaning and was perhaps regarded as an efficacious or potent substance, given the regularity with which it was interacted with.”

The researchers propose that these skulls were integral to rituals venerating specific ancestors rather than being part of conventional funerary practices. In many ancient cultures, ancestors were believed to hold spiritual power and function as moral guides for their communities. As the researchers explained, “The cranial cache represents a constantly changing collection, but its long duration suggests an enduring tradition of use, alteration, and augmentation.”

A) Location of Masseria Candelaro and contemporary sites in southern Italy mentioned in text. B) Sites in the vicinity of Masseria Candelaro. [University of Cambridge

At Masseria Candelaro, the skulls likely represented “working ancestors,” actively circulated and manipulated to emphasize their contextual significance over physical preservation. In some cases, the bodies of specific individuals or ancestors may be preserved to enable their display or participation in processions, keeping their presence active within the community.

Once created, ancestors assume a social role. Their remains develop an ongoing biography that includes the use, modification, exchange, and eventual disposal.

Although the final arrangement of the skulls in Structure Q appears ceremonial, researchers suggest it was more likely a “post-use-life decommissioning” of these powerful objects. In other words, once the skulls had served their ritual purpose, they were symbolically retired by being lightly covered with soil and left in a pile.

The researchers said that after up to two centuries of use, around 5450 BCE or later, this collection of ancestral crania and mandibles was deposited in Structure Q, within a specific area on the surface of its upper levels. The crania were not formally buried but may have been lightly covered with soil or placed in an organic container. Around 5400 BCE, the final cranium was added to the top of the assemblage. This act of deposition may not have been a significant ritual event but rather a simple and unceremonious final disposal of a well-used collection of crania at the end of their functional life.

The findings challenge oversimplified views of gender and power dynamics in Neolithic southern Italy. “While adults of all ages and both sexes are represented in these burials, infants and children are rarely encountered, perhaps reflecting a distinction in their status as persons or their potential to become ancestors,” they wrote. However, the researchers advise against interpreting this as evidence of a male-dominated society. Instead, they propose that the practice may reflect specific kinship or ritual identities within a heterarchical system, where age and gender play diverse and interconnected roles.

This discovery adds a previously undocumented layer of complexity to our understanding of prehistoric rituals in the region. It provides fresh insights into Neolithic funerary practices and the intricate ways ancient societies engaged with their dead. The rare cranial curation broadens our understanding of ritual behaviors in European prehistory and may shed light on how ancestors became ancestors and were then actively engaged.

The meaning of “ancestors” at Candelaro revolved around the symbolic power of human bones, likely tied to how the community defined its identity. At Candelaro, ancestors were not carefully preserved but actively used. These “working ancestors” were handled and circulated in dynamic ways that prioritized their ritual and social significance over their physical preservation.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.