One of my favourite things, both as a historian and a Pagan, is discovering elements of pre-Christian belief and practice that have been woven into European Christianity. These syncretic rituals and folk beliefs tell us so much about the lives of ordinary people, before, during, and after the process of Christianisation: the things they valued, the things they feared, the rhythms of their year.

Recently I learned of the survival of an ancient Greek ritual food well into the present day, through its adoption and adaptation by the Greek Orthodox church, and knew it was the perfect subject for my column. This is polysporia, the dish of “varied seed.”

Made up of a mix of all the grains, legumes, and edible seeds grown in any given area, polysporia belongs to that most fundamental class of agricultural ritual: the kind that gets down to the bare bones of the relationship between man and gods, expressing plainly what we want and what we’re willing to give in exchange.

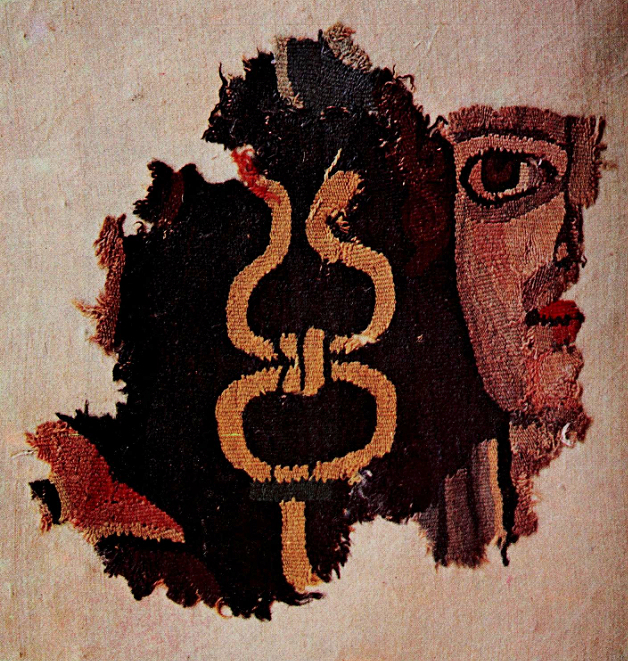

Hermes and caduceus, Loulan tapestry, 3rd century CE [public domain]

Ancient enough that it’s origins are unclear, polysporia, which is also referred to as panspermia in some older texts, may even pre-date Hellenistic polytheism as we know it. Some historians date it to the Minoan civilisation on Crete, a people whose gods and religious practices prior to the Mycenaean invasion remain frustratingly obscure to us. Wherever it came from, and regardless of its original cultic use, by the late Bronze Age offerings of polysporia had become integral to the rites of Dionysos, as both cthonic god and lord of the vine, and to Hermes, for his role as psychopomp, and to Demeter and Persephone, Corn Mother and Maiden.

The inclusion of Hermes among the recipients may seem strange – one of these gods is not like the others. But for the ancient Greeks the production of food was inherently tied to the cycle of death and rebirth. This tie between food and the dead is another thing that carried over through Christianisation, and it can still be seen in the contemporary folk rituals, as well as ceremonies that honour the beloved dead in Greece today.

Persephone is the queen of hell not despite, but because she is the Corn Maiden. Like other dying and reborn vegetation gods, her descent into the underworld isn’t just a symbolic death but a planting. She isn’t just the goddess of the corn; in a very real sense she is the corn itself, and her rebirth into the world above in spring is the sprouting of the crops in the fields. Hermes, as mediator between the worlds above and below, is therefore integral to this process. He serves as a bridge, and a messenger, connecting Persephone, the corn in the earth, with her mother, the generative force above, and also with us, her human supplicants.

Polysporia took on different forms depending on ritual and purpose, forms that have only multiplied and expanded as the thousands of years have gone by since its creation. Sometimes it refers to the raw mixture of grains and seeds, to be sprinkled on the ground or over the heads of participants in the ritual. Sometimes it’s a soup or a stew. On Crete, it can be a salad. Some traditional recipes create a sort of sweet wheat porridge, containing walnuts, pomegranate seeds, and honey, very like another, traditional offering made in honour of the dead.

It may be made and eaten at home, in recognition of certain holy days and seasons, or simply because the family enjoys it.Or it may be part of communal ritual, binding a community together as they reaffirm their relationship with the divine and secure blessings of rain, or harvest, or fertility and survival for the year to come.

This is what we see with the annual Kalogeros carnival, the syncretic offspring of a Dionsyian ritual to call down the rains and the adoption of Christianity, left to marinate in isolated parts of the Greek speaking world for thousands of years. The violent upheaval of the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw refugees disseminating the end result through new parts of Greece, where it’s still celebrated today. As part of the festivities, the Kalogeros, the rain bringer, visits every house in the district, where he is showered with the dried polysporia mix and given wine to drink by the mistress of the house. He then closes the ritual by symbolically fertilising the polysporia with his phallic staff, mixing earth and water together as an act of sympathetic magic to summon the rain and germinate the crops.

We see it again in the St. Andrew’s Day celebrations of parts of North Eastern Greece, where a boiled mix of polysporia is brought to the church to be blessed by the priest and then shared out amongst the community, in hopes of securing the saint’s blessing for the harvest to come. Late autumn and the end of the rainy season, brought, and still brings, the sowing season in turn, when Greek farmers take advantage of the softened soil to plant their spring crops, with St. Andrew’s Day on 30th November falling just when that work would be done. This time of year was marked in antiquity by festivals dedicated to Demeter, Persephone, and the other members of their Eleusinian cult; granting St. Andrew power over the seeds and planting his saint’s day there was an obvious and effective replacement.

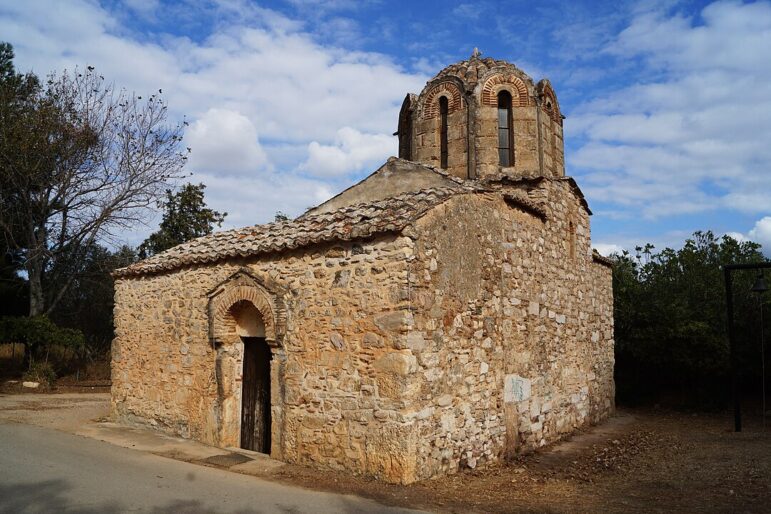

The Church of Panagia Mesosporitissa at Eleusis, Greece [Kostas Vassis, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

Most famously we see it at Eleusis, home of the Eleusinian Mysteries, where the church of Panagia Mesosporitissa, “Our Lady of Sowing”, now stands within the former temple grounds. Here the Virgin Mary, in her role as mother of all, takes over from Demeter as the patron of agriculture and provider nourishment to mankind – a role which is exemplified in the celebration of the Feast of the Entrance of the Theotokus into the Temple on November 21st.

The night before the women of each household would bake loaves of bread and prepare a pot of polysporia, visiting and borrowing from each other any missing components to make sure their household’s offering was complete. The next morning a small portion of the polysporia would be left at the town’s fountain by a member of each household, once again harking back to the Corn Goddesses and their connection to springs and flowing water, before delivering the rest of it alongside the bread to the Orthodox church, where it would be blessed in the name of the Virgin by a priest.

Finally the bread and polysporia, here a sweet, porridge like mix, heavy on wheat berries and finished with pomegranite and raisins, would be distributed among the worshippers, binding the community together in their submission and supplication to the divine.

From Eleusis, this syncretic rite spread across Greece, becoming a standard part of the Greek Orthodox ritual calendar for centuries, until industrialisation and the radical cultural changes of the 19th century saw it fade from use. Eleusis, fittingly, was the last hold out, and it is Eleusis again where the tradition has been brought back, with local women and the church of Panagia Mesosporitissa working together to recreate it for several years. The government in Greece has even applied for UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage status for it, citing its long history of adaptation and survival, changing to meet the people’s fluctuating needs over the centuries.

I think, with the looming climate crisis, it’s no surprise that this, and other practices like this, are seeing a resurgence. People feel the need to reconnect with the natural world now it’s become impossible to live insulated from it. But of course there’s more to it than just that; there always is. As someone who isn’t Greek, viewing the culture from the outside, I can’t speak on the nuances of it. I do think it’s beautiful, and that rituals like this help ground us in the here and now, connecting us to both the land and it’s spirit in ways that can only benefit us all.

Grains [matthiasboeckel, Pixabay]

Polysporia

While I myself am not a Hellenic polytheist – as I said in an earlier column my own practices are rooted closer to home – I think contemporary recipes for polysporia, as well as the historical and archaeological research into it’s older forms, could be incredibly useful resources for those that worship the cthonic-agricultural gods of the region.

This is also the second time that, for all that this is in fact a cookery column, I’m not going to give you a recipe to follow. This isn’t my culture, it isn’t my tradition, and there are so many wonderful Greek cooks and historians out there who have made their recipes and research available for free that I’m going to encourage you to look at their work instead.

- Polysporia as Cretan salad

- Polysporia two ways (soup or salad)

- A different take on it as soup

- Another soup

Unfortunately I can’t find an English language recipe for one of the sweet variations, but if anyone does (or figures out how to make it) please let us know!

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.