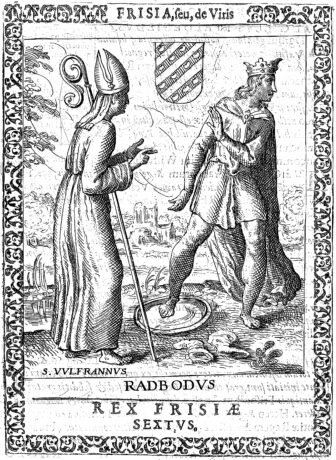

Way back around the year 700, the pagan king of Frisia – a land now divided between the northern bits of Germany and the Netherlands – was about to be baptized.

King Radbod stood with one foot in the baptismal font, ready to step into the holy water, renounce his pagan religion, and forever accept Christianity as his faith.

With one wet foot, he hesitated and asked a final question of Wulfram, the Christian missionary overseeing the baptism.

Illustration of Radbod’s wet foot from Frisia Seu de Viris Rebusque Frisiae Illustrus (1600s) [Public Domain]

Insisting that Wulfram swear an oath in the name of the Christian deity, Radbod demanded to know the truth: were the past pagan kings, princes, and nobles of the Frisian people to be found in heaven or hell?

Without doubt, Wulfram replied, Radbod’s unbaptized princely predecessors were surely damned for eternity.

The pagan king immediately pulled his foot back from the baptismal water and declared that he could not go to an afterlife without his noble precursors and had no interest in spending eternity with a few poor people in heaven.

At least, that’s what we’re told in the Life of Wulfram, a hagiography of the saintly missionary composed in the 740s.

Today’s practitioners of Ásatrú and Heathenry – new religious movements inspired by past paganisms of northern Europe – turn to this tale as evidence for the importance of ancestor worship in the long-ago time and for belief in reuniting with deceased ancestors in some form of pagan afterlife.

Like most of the ancient texts mined by modern Heathens for religious information (bar some short carvings and engravings), this narrative was written by Christians for Christians. Like many other supposedly historical accounts, it was written decades after the event it purports to describe by someone who was not at the event.

Unfortunately, also like many other pagan-ish texts, it has more to do with internal church arguments over Christian theology than with actual pagan worldviews.

In this case, it’s part of the dispute between Boniface and Clemens over the salvation status of past pagans who died without receiving baptism. The argument was related to questions of church construction on pagan burial sites and of what to do with the old bodies when the ground was being newly consecrated.

As in other medieval texts, what appears to be a record of pagan pronouncements seems to instead be a polemical parable designed to further one side of the argument – in this case, that the pagan dead are not welcomed into heaven.

Even in my retelling above (the original Latin text and a scholarly translation with detailed analysis can be found in this excellent article from 2015), it’s pretty clear that Radbod’s concerns are at least as much about class hierarchy as they are about ancestor veneration.

Like leaders of the early Christian church, he openly believes that social divisions in this life continue into the next one. No supping with the poors for this kingly fellow!

Even apart from the Christian theological nature of the tale, is this classist message really something that today’s Heathens should be taking to heart?

Elves and ancestors

Preserved in the late 14th century Icelandic manuscript compilation known as Flateyjarbók (“book of the flat island”), the tale of the 9th-century Norwegian king Ólaf Gudrødsson tells of him instructing his subjects to build a large mound for his imminent death and requiring every man of importance to place a half-mark of silver inside.

Ólaf also tells his people that “there must be no following the example of those who sacrifice to dead men in whom they put their trust while they were alive, because I do not believe that the dead have any power to help” (Hilda Roderick Ellis Davidson’s translation) and insists that heathenish sacrifices made to him after death will turn him into a troll.

Sure enough, when a famine arrives after his burial, his people “resorted to the plan of sacrificing to King Olaf for plenty, and they called him Geirstaðaálfr [“elf of Geirstad”],” evidently asserting his transformation into a helpful elf rather than a harmful troll.

Again, we have a Christian writer telling a tale of the olden days for Christian readers. Again, Christian polemic drives the telling – in this case, a distaste for what Davidson calls “an active cult of the dead in Scandinavia” that is “obviously misunderstood” by the medieval author.

And, again, we have a tale that places class hierarchy at the center, here seemingly mixing together tax paid to the living king and sacrifice made to the dead one.

Notably, what may be the little kernel of past pagan practice at the core of this tale is the making of offerings to a dead figure who is not a blood ancestor but rather someone who is seen as important to the still-living and who hopefully can have a positive impact on their continuing lives.

Here is something that today’s Heathens can heartily take to heart.

For nearly a decade of group practice, those of us in Thor’s Oak Kindred have defined ancestor in ancestor veneration to mean “someone no longer alive who is important to us.”

For many American Heathens, a resolute focus on blood relationships in ancestor veneration inevitably dovetails with neo-völkisch ideas about race determining religiosity. Even in so-called “inclusive” Heathenry, ancestor rites can drift well over the boundary into Third Reich Blut und Boden (“blood and soil”) white nationalism.

We consciously broadened our own definition, theology, and practice to embrace a wider concept of who the ancestors are that we choose to venerate in our blóts, the group rites that we celebrate together throughout the year.

Rather than being focused on class (as in the Radbod story) or blood relationship (as in much of American Heathenry), we focus on those whom we consider important to us and deserving of thanks and veneration.

American history and Malcolm X

For me, the roots of this approach are probably back in 1988, in the summer before junior year of high school.

At Evanston Township High School, the teacher of American History AP was just the right amount of eccentric. One of his idiosyncrasies was that he required an audition to get into the course.

During summer vacation, that sacred time in the 1980s when days were endless, Lake Michigan beaches were full, the forest preserve was invitingly shady, and the Green Bay Trail challenged you to see how far north you could ride your mountain bike, Mr. Mumbrue mailed each of us a list of American history texts and an assignment.

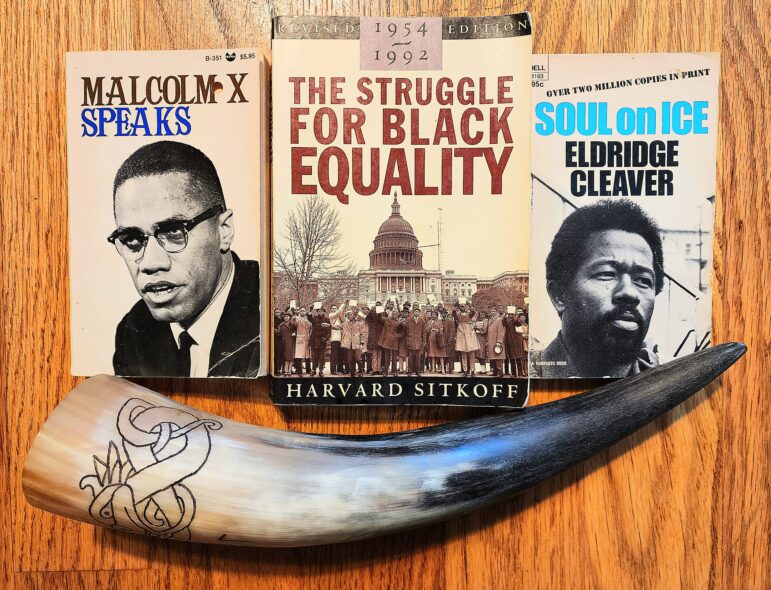

We had to pick a book from the list, read it, and write a detailed report, all during the summer and all before the new school year began. I chose Harvard Sitkoff’s The Struggle for Black Equality, 1954-1980.

I had spent my childhood attending Martin Luther King, Jr. Experimental Laboratory Schools K-8, where we were multicultural long before it was cool. We celebrated holidays from multiple religious traditions. We had guest performers from Native American, African-American, Jewish-American, and a multitude of other cultural perspectives. We had rallies in the auditorium to celebrate the Civil Rights Era and regularly sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (a.k.a. “The Black National Anthem”).

The Sitkoff book seemed like a natural choice, but – unlike the nostalgic feel-good sing-along celebrations at my grade school – reading it was like watching a horror show.

It’s a history of the era for grown-ups, an unflinching portrayal of the extreme violence and utter brutality committed by white people upon African-Americans of all ages who dared to demand basic human equality.

There was no question of who was on the right side of history. The ugliness and violence of the white hatred was disturbing and disgusting. The strength and determination of the Black hope was incredible and inspiring. Mr. Mumbrue knew what he was doing.

From there, I moved on to books like Malcolm X Speaks (the 1965 collection of speeches and statements by the civil rights leader who was never really mentioned at my school named for Martin Luther King, Jr.) and Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice (the 1968 autobiography by the leader of the Black Panther Party who was definitely never mentioned).

Malcolm X Speaks, The Struggle for Black Equality, Soul on Ice, and the Thor’s Oak Kindred drinking horn by Jóhanna G. Harðardóttir of the Ásatrúarfélagið [Karl E. H. Seigfried]

These books helped form who I became as an adult with an adult understanding that the people who positively impact our lives at a deep level – the people who change the world for the better – are not necessarily the most virtuous or the ones with the spotless records of absolute purity so often demanded by today’s younger generations of what used to be called liberals.

What matters is that they performed deeds that matter.

Fast forward nearly four decades on the VCR of life, and I stand around the tree with members of Thor’s Oak Kindred, listening as each one of us takes a turn with the drinking horn during the ancestor round to remember, to speak, to thank, and to make an offering.

LGBTQ+ activists, climate change crusaders, civil rights leaders, authors, artists, musicians, athletes, and many others who have impacted our lives have been hailed over the years. So have mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. So have family friends and colleagues.

What matters is that they matter to us.

Blót heathens and the doing of deeds

A question I often ask myself is are we worthy of them?

Yes, we say wonderful things over the horn at blót. I’ve heard people share intensely personal and deeply meaningful stories as they honor the ancestors to whom they’ve chosen to make the offering.

Yes, we honor the ancestors while standing around the oak tree or around the altar table. I’ve learned about many wonderful departed people who have had powerful effects on those who speak of them, and I’ve joined my hail to theirs to salute these impactful individuals.

Whatever we say about the ancestors at blót, are we living our lives in ways that turn words into deeds that measure up to theirs?

However we honor the ancestors at blót, are we honoring them in our lived lives?

I’ve written before about the danger of becoming a “blót Heathen.” Like a “Sunday Catholic” who is extremely devout on Sunday mornings but lives a decidedly un-Christian life for the rest of the week, we can all too easily make grand speeches over the drinking horn at blót but neglect to put intention into action when we step out into the wider world.

Are we honoring the ancestors in our lives? Or are we dishonoring them?

Do our deeds measure up to theirs? Are we inspired by their struggles and sacrifices to struggle and sacrifice ourselves?

Right now, we’re less than two months away from the start of Donald Trump’s revenge tour. Whatever people may have been hoping for when they voted for him – cheaper eggs, better jobs, something or other about the women’s sports they never actually watch – all of us are heading into dark times together.

Elections do indeed have consequences, and we’re about to experience the results and ramifications of the 2024 election in the United States.

Trump will control the White House, House of Representatives, Senate, and Supreme Court. Leaders from both parties are already lining up to pledge their help and support, offering anticipatory obedience even as corporate media reorients its ship to sail with the new winds blowing in from the right.

Those who thought House committees would save us, Senate impeachment trials would save us, the Supreme Court would save us, Robert Mueller would save us, Merrick Garland would save us, Jack Smith would save us, any of the judges presiding over Trump trials would save us, Joe Biden would save us, and Kamala Harris would save us have finally learned that nothing and no one will save us.

Or have they?

Dishonoring the ancestors

In the name of all the gods, goddesses, land spirits, and any elves disposed to being friendly towards us, I fervently hope that we’re not going to go back to the performative “resistance” nonsense of Trump’s first term.

One-day women’s marches in pink “pussy hats.” People who’ve never thrown a punch in their lives wearing safety pins to declare themselves “allies” of those who are violently brutalized by racist thugs (both in police uniforms and out of them). Hash-tagging #resist and #notmypresident on corporate social media while watching streaming corporate entertainment. Endlessly and impotently complaining about and tsk-tsking at each new Trump embarrassment and atrocity.

It didn’t work.

Politely limited protesting didn’t work. Complaining didn’t work. Voting didn’t work.

Can we rise to the example of the Freedom Riders, who went into the heart of darkness, looked the most evil white racists right in the eyes, and faced unbelievable violence – all to get this country to see its own ugly face in the mirror and maybe, finally, begin to actually live up to the lies it tells itself about equality and freedom?

Can we rise to the example of the Little Rock Nine, junior high and high school students with hearts as brave as any hero of Icelandic saga, Old English poem, or Middle High German epic – beautiful young Black people who dared to walk through screaming crowds of their unbelievably ugly and hideously hateful white neighbors to integrate all-white schools in accordance with the law of the land in the wake of the decision by a saner Supreme Court than our children will ever know in their own lifetimes?

Or are well all just too busy and too tired?

Of course, everybody’s overworked. I’m pretty sure that I’m working more for less pay now than I did 20 years ago. Seems like a whole lot of people are in similar situations.

In our hours away from work, is it just too difficult to get off the couch and leave our digital devices behind?

To be honest, there really is a lot of great stuff streaming right now. Even aside from all the Star Wars and superheroes, I could dive into 1970s kung fu, 1980s post-apocalypse, George Romero, Clint Eastwood, and Charles Bronson movies on Tubi, Plex, and Prime and not come up for air until President Vance’s third term.

But imagine if Martin, Malcolm, Eldridge, the Freedom Riders, and the Little Rock Nine all had said, “Sorry, we already have plans for the weekend.”

Imagine if all those other ancestors we honor and hail for how deeply their past deeds continue to positively affect our current lives had been too busy, too tired, too overworked, and had too much in their Netflix queue.

Each one of us will become an ancestor soon enough. While we’re here, will we do anything worthy of being honored when we’re gone?

Will we honor the ancestors with our own deeds, or will we dishonor them through inaction?

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.