Editor’s note: Today’s offering will naturally include spoilers for Romero’s Living Dead films. It also reflects on violence, gore, and death in the films and in the living world, including a mention of sexual violence.

Over the past month, I watched all of George A. Romero’s zombie movies and read his massive zombie novel. They were not at all what I expected.

I’m squeamish about gore on film, so I avoided the Living Dead movies for the first 50 years of my life.

Relatively recently, I became an obsessive watcher of the extremely dark (and darkly hilarious) superhero parody The Boys, and I’ve gotten very good at quickly putting my hands over the center of the screen just before someone’s head explodes or their guts get ripped out.

This newly developed dexterity has opened a whole genre of films that I assiduously avoided for so long. I even watched the original Suspiria the other night, which was a big step for me.

The dead walk in Night of the Living Dead (1968) [Public domain]

I wasn’t surprised by the gore of Romero’s Living Dead films. In fact, I didn’t really see it, except around the edges of my raised hands.

I was surprised by the sense of sadness that permeates the films, a sadness somehow flavored by both despair and hope. It’s an emotional combination that also sits at the heart of my beloved Norse mythology.

The more of Romero’s films that I watched – and especially the more of his novel that I read – the more I also found a theology bubbling up through the blood that aligns with my own theology of Ásatrú, a modern religion that revives, reconstructs, and reimagines the ancient polytheism of Northern Europe.

Horror in black and white

Night of the Living Dead (1968) is far more talky and theatrical than I expected. It seems more closely related to the set-piece TV dramas of Alfred Hitchcock Presents or The Twilight Zone than to the zombie kill-fests that Romero’s films continue to inspire.

I’ve long argued for a progressive theology of Ásatrú that engages with the myriad of issues we face in today’s world, so I was fascinated by the ways that this first feature-length film by Romero sets the stage for the engagements with questions of society and theology that are explored throughout the Living Dead series.

At the core of the first film is the conflict between two of the random characters stuck together in a farmhouse surrounded by the newly-awakened dead.

Ben, who is Black, prioritizes the survival of the group and attempts to plan a strategy that will keep them all safe until help arrives; Harry, who is white, thinks only of himself and refuses to join in the collective work that will protect everyone else. The racial tensions of 1968 rumble under the surface, ready to explode at any moment.

The movie’s ending hammers home the brutality not of living dead but of living men. Ben, lone survivor of the night’s horrors, is shot dead in the morning by trigger-happy white rural militia men.

The film finishes with shots of photos that look like they were taken by war correspondents or reporters covering lynchings, showing dead Ben being dragged out by a white posse with meat hooks and thrown onto a pile of corpses to be burned.

The 1990 remake of the film – written by Romero and directed by colleague, friend, and horror makeup legend Tom Savini – makes the comment on America’s racial sickness even more blunt. Ben and Harry shoot each other in fury even as the zombies are literally coming through the door.

Unlike the running dead of later media knockoffs, Romero’s ghouls are always shambling things, limping along on damaged and decayed legs, lifting arms that look ready to fall off, sometimes spilling their guts as they go.

The point is quite basic: we, the living, could easily have defeated the hordes if we had simply worked together and accepted the fact that our obsession with seeking solutions via violence is ultimately self-defeating.

“Respect in dying”

The elderly priest in Dawn of the Dead (1978), the second film in the series, makes this lesson clear as theological issues begin to come to the fore and intertwine with social issues during the intense housing project sequence near the movie’s opening.

A heavily armed SWAT team raids the crowded buildings, full of African-Americans and Puerto Ricans who have refused to follow the government order that “the bodies of the dead will be delivered over to specially equipped squads of the National Guard for organized disposition,” i.e. to be destroyed before they can reanimate.

The troopers find a priest who has been giving last rites to the dead. He tells them, “You are stronger than us, but soon, I think, they” – meaning the living dead – “be stronger than you. When the dead walk, señores, we must stop the killing, or we lose the war.” He means that the more living people are killed, the more living dead will rise.

At the level of plot, he’s right. By the third film, zombies outnumber humans.

At the level of public theology, the priest asks us to confront the fact that our own value systems are destroying us. Again, he’s right.

Our American fetish for guns, always more guns, as the best way to keep ourselves safe objectively makes us less safe. Our American business of selling bombs and bullets directly enables genocide and pushes the cycle of radicalization on into the next generation.

For a nation that casually and regularly throws around terms like pro-life and human rights, we spend a lot of effort promoting death and violating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

After meeting the priest, the troopers find a basement full of zombies, the after-effect of the project inhabitants refusing to turn them over to the authorities. The white trooper Roger asks, “Why did these people keep them here?” The Black trooper Peter answers, “”Cause they still believe there’s respect in dying.”

Nearly a half-century after this film was released, can we honestly say our nation believes in this respect?

Nearly half the country shrugs off video of a white police officer kneeling on an unarmed Black man’s neck for nearly 10 minutes, waving away the victim’s death as deserved. Physician-assisted suicide is only legal in twenty percent of states, denying a dignified death to the suffering ones who most desire it.

“A look at what hate was like”

This concept of respect for death, the dying, and the dead roars into the forefront of the third film, Day of the Dead (1985).

By this point, as predicted by the priest in the previous movie, the ghouls dead vastly outnumber surviving humans. A small group of scientists work in a militarized underground bunker, supposedly to find “a way to reverse the process, a way to eradicate the problem” of the nightmare epidemic, but the head of the team is actually working on a way to “condition and control” the zombies.

Judith O’Dea as Barbara in Night of the Living Dead (1968) [Public domain]

The result is an overt dehumanization of the living dead as objects to be experimented upon in a horrific manner reminiscent of Josef Mengele’s gruesome and monstrous experiments on Auschwitz prisoners. The head scientist learns that the living dead retain some of their previous life memories and are able to think and feel, yet this knowledge only drives him to commit further atrocities in the name of supposed scientific progress.

The entire bunker system, under the control of an increasingly unstable soldier and his out-of-control military group, looks more and more like an insane Nazi death camp and less like a scientific project.

By the end of the film, the zombie named Bub practically usurps the role of protagonist. His stumbling efforts to recover his lost humanity make him a sympathetic counterweight to the violent soldiers who increasingly reject their own.

As things go desperately wrong, the Black helicopter pilot John offers an explanation for the zombie plague.

We’ve been punished by the Creator. He visited a curse on us, so we might get a look at what hate was like. Maybe didn’t want to see us blow ourselves up, put a big hole in the sky. Maybe just wanted to show us he was still the boss man. Maybe he figure, we was getting too big for our britches, trying to figure his shit out.

You don’t have to be a monotheist to understand what he’s saying. Maybe it’s the Christian god, maybe it’s Mother Nature, or maybe it’s circumstantial happenstance. What matters, and what Romero’s film confront us with, is our human inability to work together to overcome the catastrophes we all face.

Eradicate a pandemic by simply wearing a mask and getting vaccinated? No, we have a right to get infected and spread the disease. Help hurricane victims by putting aside political posturing and focusing on the common good? No, we have a right to spread misinformation and gather militia to hunt federal aid workers.

Romero’s original 1968-1985 film trilogy seems all too timely today. So much for American progress.

“We are them, and they are us”

The 1990 remake of Night of the Living Dead includes a concluding lynching scene, with the posse gleefully stringing the living dead by their necks from trees and giggling at their spinning, kicking, and suffering while being used for target practice.

Barbara, a character rewritten by Romero so that the 1968 passive victim becomes the 1990 active protagonist, witnesses the lynching and other dehumanizing abuse of the living dead by the militia members and says to herself, “We are them, and they are us.”

Indeed, we are a brutal people who all too easily view our fellow people as Others, as less-than-human.

More than half of all Americans currently support Donald Trump’s plan for mass deportation of immigrants, no matter the human cost. Slightly less than half of adult Americans think that Israel’s military actions in the Gaza strip have either “been about right” or “not gone far enough,” despite the daily drip of footage showing young Palestinian children being targeted, wounded, and killed.

Twenty years after Day of the Dead, Romero’s portrayal of the living dead as sympathetic human victims goes into overdrive in Land of the Dead (2005), the first film in his second trilogy.

Pittsburgh has been made into a fortified playground for the rich and a dangerous slum for everyone else. Living humans use living dead for gross entertainment and gleefully blow them up as they raid the surrounding suburbs for supplies.

A Black zombie known as Big Daddy has, like Bub in Day of the Dead, regained some form of memory, intelligence, and agency. He is clearly disturbed by the mistreatment of the living dead and leads a zombie horde into the city.

Eventually, the electric fences built by the rich to keep the zombies out become a trap for the wealthy themselves, who are hunted down and consumed. The film concludes with the zombies leaving the city and looking for a home where they can live in peace – the same quest taken up by the movie’s surviving humans.

Is this all about our dysfunctional relationship with death, our mistreatment of those we see as Other, our obsession with building walls, or our psychotically economically stratified society?

Yes. All of the above.

National pastimes

Romero’s next Living Dead film, Diary of the Dead (2007), returns to the very beginning of the zombie apocalypse and shows it being documented by a group of college film students.

Like the 1990 movie, it ends with a shot of good ol’ boys gleefully using living dead hung from trees for shooting practice. The young woman who narrates the film tells us of the last video footage downloaded by her dead boyfriend, the student who had been using his digital camera to document the disaster.

A couple of hometown Joes who were out shooting targets. That day, they used people. Dead people. You know, just for fun. There was one target different from the rest. A woman, tied by her hair to the branch of a tree. The boys had this one setup just for kicks. They got out their favorite twelve-gauge and… Are we worth saving? You tell me.

Part of what makes Romero’s films so powerful is that they are so eminently believable. Do you have any doubt that Americans would, in the face of societal breakdown and removal of any legal consequences, not giddily descend into the depths of depravity Romero portrays?

Even with the system we have now, one in five women in the United States have “experienced completed or attempted rape during their lifetime.” Of these, one in three “experienced it for the first time between the ages of 11 and 17.” Gun violence reported by U.S. adults has similarly depressing statistics.

One in five (21%) say they have personally been threatened with a gun, a similar share (19%) say a family member was killed by a gun (including death by suicide), and nearly as many (17%) have personally witnessed someone being shot. Smaller shares have personally shot a gun in self-defense (4%) or been injured in a shooting (4%). In total, about half (54%) of all U.S. adults say they or a family member have ever had one of these experiences.

Now that only 27% of adults say that baseball is “America’s sport,” maybe we have to finally come to terms with sexual violence and gun violence being our national pastimes. The reality is far more gruesome and stomach-churning than any make-believe zombie gore served up by Romero and Savini.

Survival of the Dead (2009), the final Living Dead film made in Romero’s lifetime (a concluding film is supposedly in production) functions in the movie timeline as a direct sequel to Diary of the Dead and foregrounds both the social and theological issues that burble up through the other films.

On an island off the coast of Delaware, two inexplicably Irish families (complete with old school Hollywood “Irish” accents) feud over the treatment of the living dead. Neither side has a good ethical position.

One patriarch leads a posse around the island, seeking to keep it safe by shooting any zombies in the head, regardless of their relationship to the survivors. The other patriarch – ostensibly a man of faith – wants to keep their living dead family members close by, so that they can be cared for until a cure is found. Both are scoundrels.

The shooter is a swindler out for personal power and bloody vengeance on his more successful rival. The one who professes to care for his dead family members has actually enslaved them; his own dead wife, chained like a rebellious slave, serves him by cooking his meals in the kitchen.

The two old men refuse to abandon their old feud, even as the numbers of the living dwindle and the numbers of living dead rise. In the end, the two of them kill one another, rise again, and endlessly click empty guns at each other – failed patriarchs whose hatred for their neighbors and love of violence continues beyond the grave.

Can we honestly say our own value systems, our own ethical systems, or own faith systems are somehow superior? How would each of us act when faced with a terrifying apocalypse?

I think our own behavior during the past pandemic and current genocide answers those questions.

Under the sun

Eleven years after Romero’s final zombie film, The Living Dead (2020) was published. Completed by Chicago’s own Daniel Kraus from material left unfinished at the time of Romero’s death in 2017, the novel takes over 600 pages to weave a complicated narrative tapestry that always remains deeply personal.

Beginning at the very beginning of the zombie epidemic and continuing through its end 15 years later, the novel follows a kaleidoscope of characters as diverse as this nation we live in today.

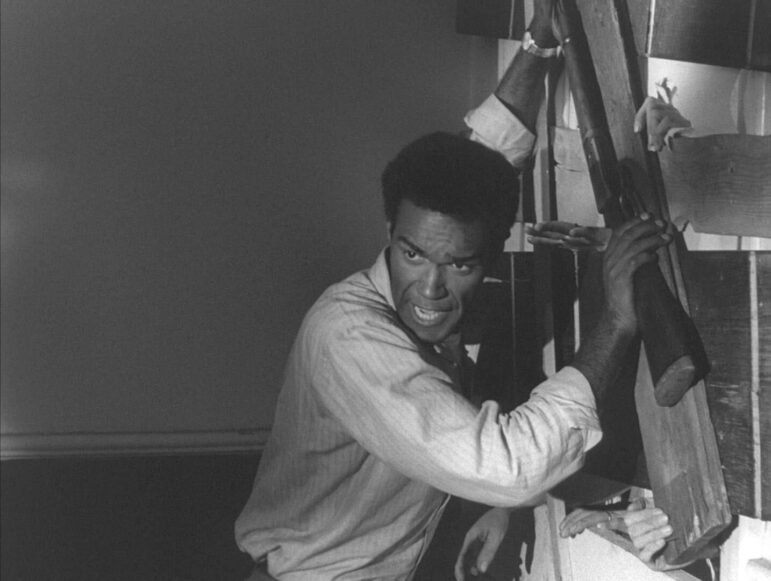

Duane Jones as Ben in Night of the Living Dead (1968) [Public domain]

The cover blurb shouts out that the book is “a work of gory genius,” but the true brilliance of the book is in its unvarnished expression of Romero’s final thoughts about life in this world, even as he faced his own death from aggressive lung cancer.

The mood is one of resolute hope in the face of utter despair, of holding a tiny spark of joy amidst overwhelming sorrow, of finding moments of transcendent beauty within years of grinding horror.

Like the Living Dead films, the novel isn’t exactly scary. Rather than shivers, the words bring tears.

An assistant to an assistant medical examiner lovingly cares for him as he slowly and painfully dies from a zombie bite from his undead mother.

A teenage girl tries and fails to convince her pacifist blues singer beloved to fight the living dead rather than hand himself over to them.

An autistic, asexual, nonbinary government statistician spends the apocalypse happily alone in her abandoned workplace, collecting and transcribing a massive oral history of the epidemic from years of telephone testimonies, then watches all her work burn as the humans who outlive the catastrophe immediately begin killing each other and destroying the new society that was being born out of the ashes of the old.

I fell in love with all these characters, along with many others whose tales form strands within the carefully constructed web of the novel. They may all be tragedies, but they are beautiful tragedies, as we can only hope our own lives will be.

In this book, the concepts and questions of Romero’s films are fleshed out, developed, and interrogated without the budgetary restraints or meddling company men he faced while making them. It’s not a what-may-have-been tale, however, for his movies are perfect as they are. Instead, it’s a glimpse into the unfettered imagination of a visionary in a medium where he was free to communicate his ideas without limit or compromise.

In the end, the novel is a portrait of our relationships with life, death, ourselves, and each other.

What makes Romero’s living dead so unsettling is not that they are monsters from beyond. What makes them deeply disturbing is that, as the 1990 version of Barbara says, “We are them, and they are us.”

We are, each of us, every character who struggles against the living dead who seek to pull us into themselves and make us one of them, for we all look at the cemetery we drive by and know that we will someday join that silent community.

The rot of the zombies – their flesh falling off, their jaws gaping, their skin ripping, their intestines pouring out – is so disgusting because we know that our bodies beautiful will, all too soon, also become things ruined by trauma, disease, and decay.

As in mythology, Romero uses fantastic creatures in order to shake us into considering deeper questions than the everyday ones we face while scurrying about under the sun as it rushes across the sky.

Our death

Like many modern practitioners of Ásatrú and Heathenry, one of my foundational experiences was reading Hilda Roderick Ellis Davidson’s classic popular study Gods and Myths of Northern Europe (1964). The scholarship may be old, but her all-encompassing approach and deeply considered synthesis of seemingly disparate elements continues to be inspirational.

Here’s something I wrote for The Wild Hunt back in February about coming to think of her as the Dream Killer.

Her commonsense explanations of mythological mysteries – the eight-legged horse Sleipnir as “the bier on which a dead man is carried in the funeral procession by four bearers,” Valhalla as “a synonym for death and the grave, described imaginatively in the poems and partly rationalized by Snorri” – made so much sense that they squashed any small hope that the magic of the myths might just possibly exist.

I have long believed that literally (mis)reading religious texts such as myths and poems has caused and does cause many of the great evils of this world. Davidson’s insistence on drilling down into mythic and poetic imagery, while perhaps crushing dreams of magic, also feels right and proper.

This column began by stating that the ideas percolating up in Romero’s Living Dead films align with my own Ásatrú theology. The Davidsonian method helps explain what I mean.

What are frost giants? In the myths and poems, they are the great enemies of the gods, yet they are also their mothers. They seek to take the daughters of the gods, yet they also provide their brides.

What is the thing that takes away life, but also provides solace for the suffering? Our death.

What else are frost giants? They are cold, just as the dead buried in hard northern soil are cold. They take the golden apples of youth from the gods, leaving the divinities to wither with age. The frost giant wizard-king Útgarða-Loki (“Loki of the Lands Outside the Fences”) was nursed by Old Age herself, who defeats all and even brings Thor down to one knee.

What is the thing that chills us to the temperature of the ground, destroys all youth, and conspires with old age to bring us to our final defeats? Our death.

What are dwarfs? They are pale creatures, dwell inside the earth below rocks, and are associated with the maggots that writhe in the ground.

What is the thing that frightens us with its paleness, can be found below the ground beneath a stone, and is devoured by underground maggots? It is us, after our death.

Who fights hardest against the frost giants, sends a dwarf into a funeral pyre, and prevents a dwarf from stealing his daughter away?

Thor, the god associated with protection of the both the living and the dead, with sacred fires and funerals, and with defense of the community from harm.

He is also the god associated with rebirth – positive rebirth, not the walking death of Romero’s films.

Thor uses his hammer to bless the bones of his goats after eating them, and they return to life. He uses his hammer to bless Baldr’s funeral pyre, and the bright god returns to life after the devastation of Ragnarök.

Baldr returns, death defeated, and joins with his likewise returned-from-death killer to build a new community and lead it into a new golden age of peace.

This is nearly how The Living Dead ends. Nearly.

Life itself

Romero’s surviving characters – physically, emotionally, and mentally scarred from spending long years fighting for their lives – finally come to terms with an understanding that the living dead are us, with the realization that we are all the same.

They build a new type of human community that consciously spurns the failings of the world before the apocalypse. They put away their guns in a brick vault with no door. They care for the last of the living dead as they decay into a final death. They care for their neighbors by sharing all work and resources, by embracing responsibility without power. They also care for each other by standing by and offering their love when one of them breathes their last – death with dignity.

This dewdrop world—

Is a dewdrop world,

And yet, and yet . . .– Kobayashi Issa

The joy of the beauty that Romero celebrates is always tinged with the pain of the darkness that he knows is always there.

An American survivor arrives at the new utopian community in Canada, a crass and vulgar man who refuses to contribute any actual productive work to the group, who encourages hoarding of resources rather than sharing, who dehumanizes those he sees as rivals and enemies, who demands that walls be built to fend off the hordes of invaders he insists wait just outside, and who finally whips the community into a bloodthirsty frenzy by appealing to their deepest, darkest, most hateful, and most selfish desires as he points them at a defenseless enemy within their own community.

Just when everything seems set for a new world avoiding the fatal mistakes of the old, an evil that all of us clearly recognizes rises up and tears it all down.

Völuspá (“Prophecy of the Seeress”), the Old Icelandic poem that is the source for so much of what we know about Norse mythology, ends – after the return of dead Baldr with his dead killer and the building of their new utopian community – with a dual image.

A hall she sees standing, fairer than the sun,

thatched with gold, at Gimle [“protected from fire”];

there the noble fighting-bands will dwell

and enjoy the days of their lives in pleasure.There comes the shadow-dark dragon flying,

the gleaming serpent, up from Dark-of-moon Hills [Old Icelandic Niðafjöll];

Nidhogg [“hateful striker”] flies over the plain, in his pinions

he carries corpses; now she will sink down.(Larrington’s translation)

The American writer and the Icelandic poet paint parallel pictures of imagined future utopias that rise from the ruins, both forcing us to face the same truths.

We cannot defeat death, and we are doomed by our own hatefulness and lust for violence.

And yet, there is hope.

Several years ago, I wrote about lessons taught by myths of Odin.

Doing everything we can to provide a better foundation for future generations is of prime importance. The continuation of the human story is what really matters. The wider world is more important than the inner one, and we would do well by turning away from our spiritual self-absorption and into the bigger narrative.

There will always be death. There will always be violence. There will always be men who seek to turn us against each other.

But there will also be life. There will also be love. There will also be neighbors who seek to join together on this journey.

We can embrace both sadness and joy, both despair and hope.

To do any less would be to deny life itself.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.