Last weekend, on the eve of the equinox, the members of Thor’s Oak Kindred gathered to celebrate our annual fall blót to the Norse god Týr

At that balance point in the year, when summer gives way to autumn and the nights begin their slow growth to midwinter, we honor the god of gods, the god whose name itself means “god.”

Blót is the central ritual of Ásatrú and Heathenry, new religious movements inspired by Old Norse paganism. In our group, we offer ale to the deities and land spirits as we honor them, thank them for past gifts, and ask for further gifts in the coming season.

When I’m preparing what I’ll speak over the drinking horn as we pass it around the oak tree, I like to review the material about that particular blót’s particular deity that survives from the long-ago time.

For the god Týr, there are two central concerns. The first is commonly referenced by modern practitioners, the second maybe not so much.

Týr and Ásatrú ethics

In the Old Norse corpus, we really only have the one major myth of Týr.

In the endnotes to The Elder Edda: A Book of Viking Lore, Andy Orchard sets out a compelling argument that Loki, not Týr, is Thor’s companion in the poem Hymiskviða (“Song of Hymir”). So, we just have the one myth left.

The tale of Týr and the wolf Fenrir is alluded to in the poem Lokasenna (“Loki’s Quarrel”) and is told in fuller form by the Icelandic antiquarian Snorri Sturluson in his Edda of c. 1220.

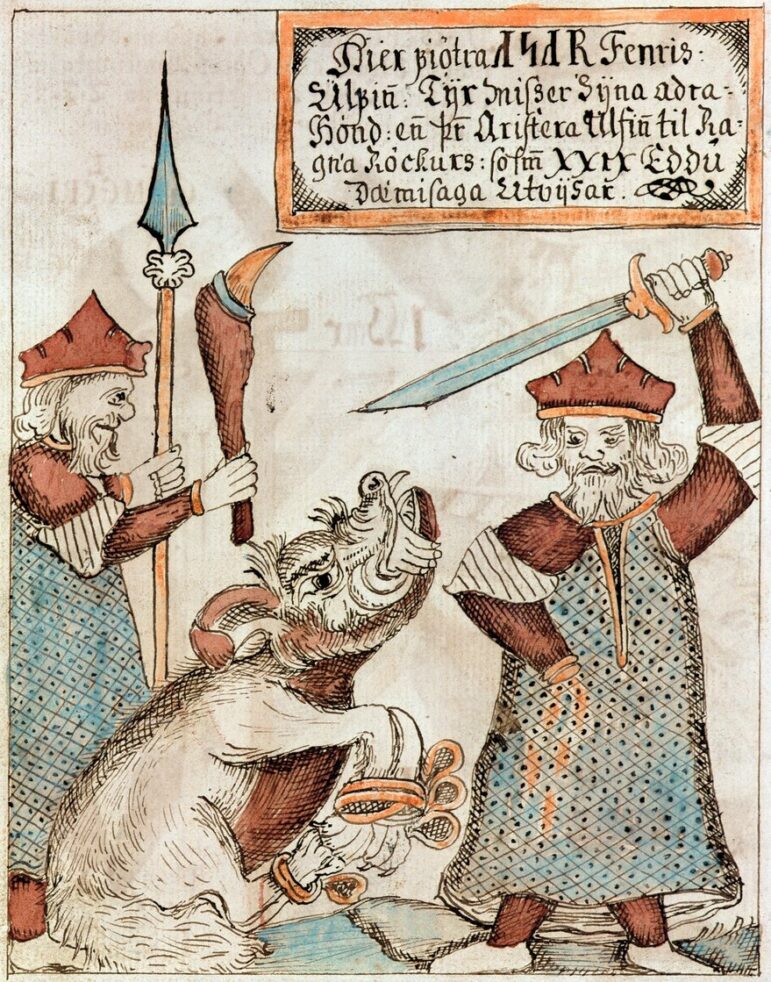

Illustration of Tŷr losing his hand to Fenrir (anonymous Icelander, undated) [Public domain]

Here’s how I summarized the story several years ago, in my article “Týr and the Wolf in Today’s World.”

[Tyr] appears in the Edda when Snorri Sturluson tells the tale of the gods attempting to neutralize the existential threats of Loki’s three monstrous children: the half-corpse Hel, the gigantic World Serpent, and the monstrous wolf Fenrir.

At first, the gods keep and raise Fenrir, and only Tyr is brave enough to feed the growing wolf. However, Fenrir’s rapidly increasing size and the prophecy that he is destined to attack the gods leads the deities to attempt his binding for their own safety. The wolf manages to break out of the various fetters placed on him under the guise of a game, so the gods ask the clever dwarfs to make an unbreakable band.

The gods then take Fenrir to an island overgrown with heather and tell him that, if he is too weak to break the new fetter, they will know he is no threat – and he will then roam free. Understandably suspicious that they will leave him in bonds, he asks to hold a god’s hand in his mouth as a guarantee of their good faith.

Tyr volunteers his own right hand. When the gods see that the wolf is unable to break free from the dwarf-forged fetter, “they all laughed except for Tyr. He lost his hand.” Thanks to Tyr’s sacrifice, the wolf is now bound for the coming ages and will be a captive until the arrival of Ragnarök.

At the first level, the theology of the tale is straightforward: the god stands up to a dangerous force and takes harm onto himself in order to protect the wider community.

At the second level, the applied theology is also plain and of the “as above, so below” variety: as the god was willing to accept harm to himself as the cost of protecting the community, we should also be willing to take the hits that come with publicly standing against harmful forces.

It’s at the third level, that of ethics, that we have to go a little deeper.

Myths are not literal. This is not a tale of mistreating an adorable little wolf cub, cute in his newborn innocence and deserving of a happy life in a wildlife refuge.

As per philosopher Paul Ricœur, mythology is “a species of symbols” and myths are “symbols developed in the form of narrations.”

It’s pretty clear that Fenrir is a symbol of forces that are harmful to the community, not a lupine naïf.

Interpretations that insist the myth is about a cruel and dishonest god betraying the trust of a kindly and innocent puppy get stuck at the literal level while overwriting the basics of the tale with contemporary concepts of aspirational victimhood and the post-Bruce-Lincoln idea that the Norse gods are the villains of their own myths.

They also brush past the ethical fundamentals of Ásatrú.

We can relate the tale of Týr and the wolf to wider Ásatrú ethics by turning to Hávamál (“Sayings of the High One”), the Old Norse poem that provides so many insights into moral concepts of the earlier pagan era.

In the poem, the often-mysterious god Odin is extremely clear about relations between friends versus relations between enemies. There is an entire section of the poem on how we interact with those who bring harm.

Here it is, in Carolyne Larrington’s popular translation:

42. To his friend a man should be a friend

and repay gifts with gifts;

laughter men should accept with laughter

but return deception for a lie.43. To his friend a man should be a friend

and to his friend’s friend too;

but no man should be a friend

to the friend of his enemy.44. You know, if you’ve a friend whom you really trust

and from whom you want nothing but good,

you should mix your soul with his and exchange gifts,

go and see him often.45. If you’ve another, whom you don’t trust,

but from whom you want nothing but good,

speak fairly to him, but think falsely

and repay treachery with a lie.46. Again, concerning the one you don’t trust,

and whose mind you suspect:

you should laugh with him and disguise your thoughts:

a gift should be repaid with a like one.

Subtle and difficult to understand, this is not.

There’s also the oft-cited ending to verse 127:

Where you recognize evil, call it evil,

and give no truce to your enemies.

Again, this is neither elusive nor enigmatic.

The poem, so often cited by modern practitioners as forwarding a Heathen ethical system, really hits the reader over the head on this particular subject. There’s no equivocating, no allusive language – just a straightforward injunction on how to deal with someone who is harmful to the community.

Týr clearly does what is right and proper according to the plainly denoted ethics on this issue.

Heathenry does not follow the supposedly universal “golden rule” or forward Christ’s concept of turning the other cheek. It does not internalize Michelle Obama’s motto “when they go low, we go high.”

No, it’s a basic and fundamental tenet of Heathen ethics that we not only have no responsibility to make fair and equitable deals with those who mean us harm, but that we actually have a duty to stand against the harmful ones and fight them with full force.

At the fourth level, that of applied ethics, the deeds we must do are also straightforward.

Don’t welcome harm-bringers into your community. Don’t cover for abusers. Don’t make excuses for racists. Call them out and kick them out.

Don’t fuss around with being fair to the harmful. Don’t worry that the sexual assaulter’s feelings may be hurt when you report him to police. Don’t give second chances when you find out someone is a white nationalist.

Do follow the model of Týr and the teachings of Odin. Immediately quit any group that protects abusers and coddles racists. Go public with what you know. Make formal police reports and go on the record with the media.

Yes, both the harm-bringers and those who make excuses for them will be mad at you. Yes, they will go after you online and in-person. Yes, things will get a bit miserable with people you had considered your friends.

Nobody – least of all the gods – said this would be easy.

Týr as guiding light

Given the dearth of detailed myths about Týr, I do think today’s Heathens should consider one particular verse from the Old English Rune Poem.

Probably composed around the year 1000, but preserved in a printed edition of 1705, each verse of the poem names and explains a rune of the Anglo-Saxon runic alphabet known as the futhorc.

The 1915 edition edited by Bruce Dickins provides the relevant verse in a somewhat archaic translation:

Tiw is a guiding star; well does it keep faith with princes;

it is ever on its course over the mists of night and never fails.

This short verse provide some interesting information that widens the scope of our lone Norse myth.

Tiw is the Old English version of the Old Norse Týr and, via the OE Tiwesdæg (“Tiw’s day”), gives us our modern word Tuesday.

The rune in question is called Týr in both the parallel Norwegian and Icelandic runic poems.

Týr rune chalked onto tree for fall blót [Photo by Karl E. H. Seigfried]

It looks like an arrow pointing straight up, which makes sense with the identification of Týr as a guiding star – the north star that provided a dependable means of navigation for long-ago followers of the gods and goddesses, a directional beacon that was ever-faithful and never-failing up in the highest sky.

That identification doesn’t necessarily mean that the star was then (or should be now) literally identified as the god Týr. Instead, as poetry so often does, it makes a parallel and suggests symbolic meaning.

As we identify the oak with Thor, we can identity the north star with Týr. Both can be focuses for mediation, reflection, and ritual.

For those of us who travel for work, who must ride the tollways between states late at night, it can bring comfort to gaze up and see the sign of Týr watching over our way from far above.

Such is the literal reading of the verse. A deeper reading can reveal a new road for modern theology and its application.

From our theology of the divinities, we know that Odin is magical, mysterious, multivalent, and not always dependable. Thor is often away in the east, smiting trolls. Like Odin, Freyja wanders the world on her own missions.

Týr, however, guides us, keeps faith with us, stays the course us, and never fails us. In the sometimes-wild world of the Norse deities, that stability and faithfulness can bring great comfort to those who seek it.

For those raising their hands and objecting but he broke faith with the wolf, please see the section on the non-necessity of dealing fairly with harm-bringers above. Practitioners and devotees have, by definition, a different relationship with deities than those who bring harm against us have with them. It’s all of a piece.

How many have been told by Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, and similar 12-step program groups that they must turn to a “higher power” for defense and restoration? How many have been turned off by the monotheistic resonances of this mantra?

Heathens and Pagans overcoming addiction can instead turn to the faithful and never-failing god who guides and walks with us on the way that lies “over the mists of night,” above the painful miseries of withdrawal and longing – the god who is also willing to take harm unto himself to protect members of the community from harm.

That wonderful combination of qualities can also be deeply meaningful in other situations.

Are you caught in the crossfire of a divided family, with each side demanding your allegiance? Týr can help illuminate the path.

Are you out of prison and trying to resist the lure of the old, dark ways that landed you there in the first place? Týr can guide you along the right road.

Are you a witness to abuse within your family, community, workplace, or religious organization? Týr can offer support as you tread the hard way of reporting and testifying.

The ethical concepts of Týr encoded within the myth of his hand and the maw of the wolf work well with this starlike concept of Týr as guiding light works. The first provides a prototype for ethical behavior, and the second offers solace along its difficult path.

Finally, we can apply the divine theology derived from the runic verse to our own lives as a model.

We can ourselves be the guiding light for those in need of guidance. We can keep faith with those who need us to have faith in their hard work of overcoming difficulties. We can help others by staying the course with them and never failing when we are needed.

Is a friend being thrown out by their family because of who they are or whom they love? Help them find a place of refuge or offer it yourself.

Is a colleague being sexually harassed by your boss? Support them in the reporting process and be willing to formally add your own name as a supporting witness.

Is a fellow practitioner being targeted by racists in your religious community? Blow the whistle on the white nationalists and go as public as possible.

As so often is true when we work to follow a better way, this won’t be easy.

New horizons

My theology doesn’t have to be your theology. Your theology doesn’t have to be mine.

Despite what the media, academics, and religious organizations may suggest, there is no Ásatrú authority or Heathen high council.

Instead, there is a widely divergent range of religious beliefs, ethics, practices, and worldviews within the wider umbrella of 21st century Ásatrú and Heathenry.

It’s a bit nonsensical to make accusations of blasphemy when lone practitioners, kindred members, and devotees of larger organizations often don’t agree on even the most basic concepts.

I believe in building a public theology for Heathens of positive intent who may have interest in such a project. If they don’t, they don’t. No worries!

I believe in building a religious system that engages with our lives in the modern world but engages with the old materials in a meaningful way. My path is not dictated for any others to follow. Be true to your own way!

I choose to follow the guiding light of the faithful god who stands against the harm-bringers, and I choose to work on figuring out a coherent theological and ethical system to the best of my ability. Your path may lie on a different road!

Hey, you’re not getting any younger

The Wild West has already been won

Northern nights are growing colder

And the old eastern ways have goneSo, tonight after sundown

You must go from this place

Without a tear, without a frown

Disappear without a traceNew horizons will appear

Oh, I’m going soutbound, dear

Without a word, without a sound

I’ve got to leave this ghost town“Southbound” by Phil Lynott (1977)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.