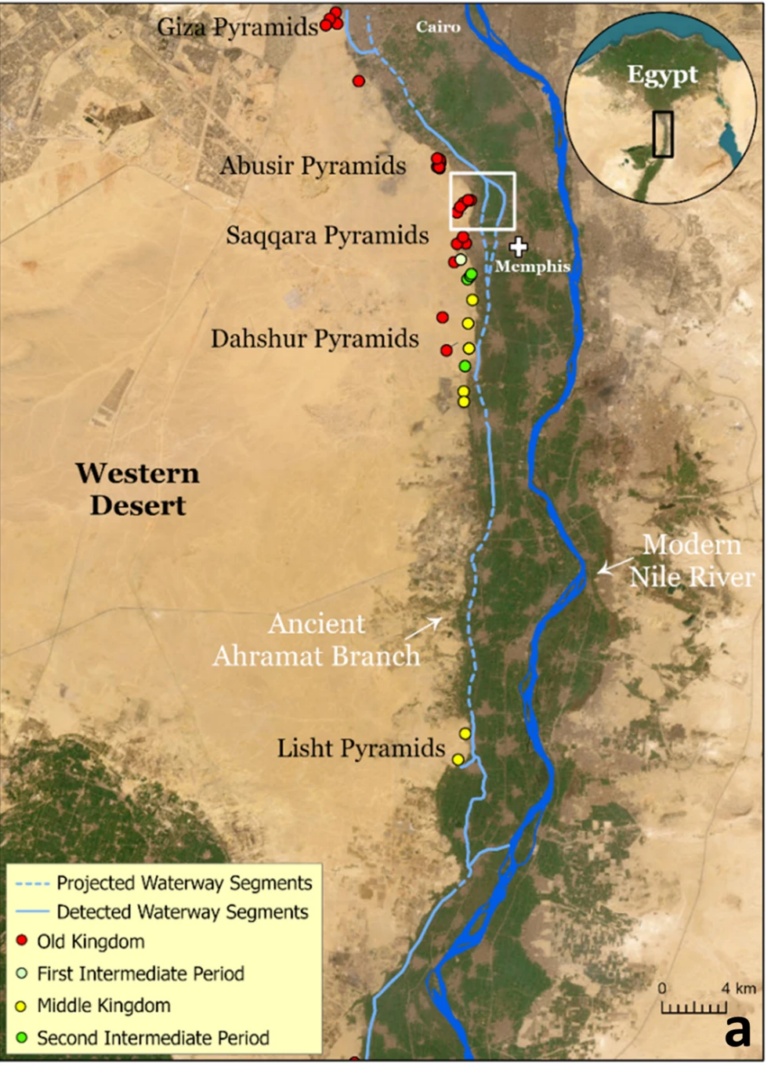

TWH – The science journal, Communications Earth, and Environment, published evidence of an ancient, now dried-up and silted-over branch of the Nile. The research is from the Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences at the University of North Carolina – Wilmington. The authors of that study, Eman Ghoneim et al., named this branch the “Ahramat Branch.” In Arabic, “Ahramat” means “pyramids.” The discovery may explain why pyramid fields were concentrated along this strip of desert near the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis, as they would have been easily accessible via the river branch at the time of their construction.

During the age of pyramid building, construction supplies moved along this branch. That waterway also brought people to perform the rituals of the Cult of the Dead Pharaoh. Ghoneim and her colleagues found that many of the pyramids had causeways ending at the proposed riverbanks of the Ahramat Branch, suggesting the river was used for transporting construction materials.

The Ahramat Branch helps to explain why the Egyptians built the pyramids where they did. The height of the water in that branch varied over time, as did the locations where the pyramids were built. The distance between the banks of that branch and the pyramids also varies.

Ghoneim et al. discussed the changes in land and water in North Africa. These changes influenced the Ahramat as well as ancient Egypt.

The Cult of the Pharaoh

No pyramid was merely the beautifully decorated final resting place of a dead Pharaoh. Pyramids formed parts of ceremonial complexes, which were key elements of the Cult of the (Dead) Pharaoh. Next to the pyramid stood the mortuary temple, where the Pharaoh’s cult continued after death. Egyptians built valley temples on waterways, and a causeway linked the valley temple with the mortuary temple.

Many of these causeways ended at and ran at right angles to the bank of the Ahramat Branch. Ghoneim et al. argued that the valley temples functioned as river harbors.

A ritualist could interpret a ceremonial complex as the built “props” of a ritual, with each structure playing a role in the ritual. One such ritual was the interment of the dead Pharaoh. Those interested in rituals can use their imaginations to envision another ritual involving offerings as part of the Cult of the Pharaoh. One can easily imagine processions walking along those causeways as part of the ritual. Ritualists may understand these valley temples as entry points on a sacred journey.

“The Ahramat Branch borders a large number of pyramids dating from the Old Kingdom to the 2nd Intermediate Period and spanning between Dynasties 3 and 13.” via Communications Earth, and Environment

Climate change in ancient North Africa

As the last Ice Age ended around 10,000 B.C.E., sea levels rose, and the area now known as the Sahara began to transform from an arid desert to a savannah-like environment with large river systems and lake basins. Scientists have labeled this period as the African Humid Period (12,500 to 3000 B.C.E.).

During the African Humid Period, increased rainfall brought large volumes of water to the Nile floodplain. From about 8000 to 4000 B.C.E., freshwater marshes bordered the swollen Nile. As the Sahara became greener, the Nile River valley became more inhospitable.

Annual rainfall in what is now the Sahara ranged between 300 to 920 mm (11.8 to 35.4 inches). Today, the eastern Sahara receives only 0.5 mm (0.02 inches) of rain per year.

The cycle shifted again when the African Humid Period ended around 3000 B.C.E. As the Sahara became more arid, the Nile became more attractive, leading people to migrate to the now more hospitable Nile valley.

The Old Kingdom of Egypt began around 2700 B.C.E.

The Great Sphinx and Pyramids of Gizeh (Giza), 17 July 1839, by David Roberts [public domain

The Ahramat Branch

The Nile had a much greater water volume during the African Humid Period, which lessened during the Old Kingdom. This period saw the Nile frequently branching off, including the Ahramat Branch. As northeastern Africa became more arid, the Nile and its branches carried less water. The desert expanded, water levels dropped, and some branches dried up.

In the developed world, rivers seldom run free and are often managed, like the Colorado River, which functions as a de facto water management system. The developed world keeps tight control over waterways. Before humans had such control, rivers meandered, branched off, flooded, and changed course naturally.

The Ahramat Branch was not a small creek. Before humans began to control rivers, their length, depth, and width varied significantly. Ghoneim et al. reported that the Ahramat had a depth between 2 and 8 meters (6.6 to 26.2 feet), a length of 64 kilometers (39.8 miles), and a width between 200 to 700 meters (656.2 to 2,296.6 feet).

Egyptian civilization developed in the context of declining rainfall, which meant less water in the Nile and its branches. As the Sahara grew larger, the risk of sandstorms increased, causing branches of the Nile to silt up. Its banks grew more solid, and marshlands disappeared. The Nile itself and its branches began to move eastward, marking the beginnings of the Old Kingdom around 2700 B.C.E.

From west to east, Egypt can be described as three regions: the Western Desert Plateau, the Nile floodplain, and the Eastern Desert. The Western Desert Plateau lies between the western border and the Nile floodplain, which bisects Egypt and provides the main water source. The Eastern Desert lies between the Nile floodplain and the Red Sea.

The Ahramat Branch flowed between the Nile and the Western Desert Plateau. According to Ghoneim et al., the volume of water in the Ahramat varied over time. When it carried more water, it overflowed its main banks and covered more ground. The distance between the Ahramat and the pyramids under construction also varied. When the water in the Ahramat rose higher, the Egyptians built the pyramids further west. When the water fell lower, they built the pyramids closer to the Ahramat Branch.

There is no consensus on why the Old Kingdom collapsed. One theory suggests that failures of the Nile to flood adequately over several years led to famine, which in turn led to the collapse of the Old Kingdom.

Soil cores extracted from the area around Memphis show 3 meters (9.8 feet) of sand, likely deposited by sandstorms from the growing desert. This sand would have pushed the Nile and its branches eastward, potentially overwhelming the Nile’s low-lying branches.

Like political boundaries, rivers can change. In 2007, John K. Hillier et al. estimated that at Luxor in southern Egypt, the Nile had migrated 2 to 3 kilometers (1.2 to 1.9 miles) per 1,000 years.

Two factors drove the eastward migration of the Nile and its branches: continued desertification of the Sahara, which increased the amount of windblown sand, and a low volume of water in the river and its branches, which caused more silting. When sandstorms and low water occurred together, the process accelerated. Additionally, northern Egypt sits on a fault line and is prone to earthquakes. Over time, fault line movements caused a relative tilt downwards to the northeast, contributing to the drying up of the Ahramat Branch.

The Ahramat Branch disappeared during the New Kingdom, roughly 1550 to 1070 B.C.E.

An early photograph of the Great Pyramid, taken by Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet in 1839 [public domain]

The zone of interest

In ancient Egypt, the major cities and monuments straddle the banks of the Nile. The ancient Egyptians built their monuments at the margins of the Nile floodplain. As the volume of water in the Nile and its branches changed, so did those margins.

Eman Ghoneim et al. examined a zone of interest west of the Nile, extending from the Lisht Pyramid complex northward to the Giza Pyramid complex. This zone contains the largest concentration of pyramids (31) in Egypt. The Egyptians built these pyramids from the Old Kingdom to the Second Intermediate Period, roughly from 2700 to 1650 B.C.E. Memphis, the capital of the Old Kingdom, is located on the Nile across from this zone. Until now, the reason for this dense concentration had never been clear. The Ahramat Branch would have provided transit for building those ceremonial complexes.

“Many of us who are interested in ancient Egypt are aware that the Egyptians must have used a waterway to build their enormous monuments, like the pyramids and valley temples, but nobody was certain of the location, the shape, the size or proximity” to the pyramids, says lead author Eman Ghoneim in a statement. “Our research offers the first map of one of the main ancient branches of the Nile at such a large scale and links it with the largest pyramid fields of Egypt.”

The Ahramat branch could have provided transport to major pyramid sites. Those sites include the Giza, Abusir, Saqqara, Dahshur, and Lisht pyramid complexes. That article quoted lead archaeologist Ghoneim. She said the Nile served as a “lifeline in a largely arid landscape.” It provided both sustenance and easy transport of goods and building materials. She continued “For this reason … most of the key cities and monuments were in close proximity to the banks of the Nile and its peripheral branches.”

Future research to identify more extinct Nile branches could help prioritize archaeological excavations along their banks and protect Egyptian cultural heritage.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.