Last week, a set of images titled “Mordor Metal Fest” drifted across my Facebook feed.

Posted in the public group “Midjourney Official,” the set of quasi-photographical images includes portrayals of Sauron on electric bass, a Ringwraith on guitar, Gollum on vocals, and beer-drinking orcs in the audience.

Generated by artificial intelligence, the visuals are clearly based on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies. The designs of the characters are straight from the films, and the image of Saruman is obviously pulled from photos of Christopher Lee in the role.

Aside from reinforcing the somewhat sad fact that personal imaginings of Tolkien’s legendarium the world over seem to have been indelibly replaced by Jackson’s cinematic designs, what immediately struck me was that J.R.R. Tolkien is possibly the wrongest author to illustrate with AI.

“Odin at Mimir’s Well” by Willy Pogany (1920) [Public Domain]

The attempt to divine what a past author would have thought of current events is usually a bad idea all around, but we do have much pertinent information in Tolkien’s case.

In J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, Humphrey Carpenter writes of Tolkien’s disdain for the supposed progress of technology. For the writer of The Hobbit, “railways only mean noise and dirt, and the despoiling of the countryside.” Even in the mid-1960s, he “did not install any electrical gadgets in the home… Not only was there no television in the house, but no washing-machine or dishwasher either.”

Carpenter also edited The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, a collection that demonstrates the author’s anti-technology bent in his own words. “There is only one bright spot,” wrote Tolkien in 1943, “and that is the growing habit of disgruntled men of dynamiting factories and power-stations; I hope that, encouraged now as ‘patriotism’, may remain a habit! But it won’t do any good, if it is not universal.”

Tolkien writes in 1944 of the “damage” done by “the growth of great flat featureless modern buildings” and even rants against radio: “I daresay it had some potential for good, but it has in fact in the main become a weapon for the fool, the savage, and the villain to afflict the minority with, and to destroy thought. Listening has killed listening.”

Instead of embracing new technologies, Tolkien preferred when “all the world is messing along in the same good old inefficient human way.”

Indeed, he repeatedly writes of the human way of creativity as “sub-creation,” a process of detailing imagined realities fundamentally different from the physical creation by the Christian god. Human creativity is, in his view, “a tribute to the infinity of [the god’s] potential variety.” The object of creativity is “Art not Power, sub-creation not domination and tyrannous re-forming of Creation.”

As the photo-like “Mordor Metal Fest” images demonstrate, AI does indeed slouch towards “tyrannous re-forming of Creation.”

A central goal of AI’s designers and customers is to generate images so lifelike that they seem like actual photographs. This goal will only get closer as the technology is developed, thus saving humans the time spent in laboring over photographing, drawing, painting, designing, illustrating, and other creative tasks.

Is this a labor that should be saved?

“Labour-saving machinery,” Tolkien writes in 1944, “only creates endless and worse labour. And in addition to the fundamental disability of a creature, is added the Fall, which makes our devices not only fail of their desire but turn to new and horrible evil. So we come inevitably from Daedalus and Icarus to the Giant Bomber. It is not an advance in wisdom!”

Given all of the above, I’m more than fairly confident that Tolkien would have been disgusted by the use of AI to generate images based on Hollywood movies based on his books – especially given his dedication to the hard creative work of illustrating his own texts and, when discussing American illustrations of his work, his expression of “heartfelt loathing” regarding “anything from or influenced by the Disney studios.”

What he writes about “labour-saving machinery” not being “an advance in wisdom” makes me wonder what relationship those who follow the Old Way in the modern world may have with artificial intelligence. What does AI mean to those of us who practice Ásatrú, a modern religion that revives, reconstructs, and reimagines the ancient polytheism of Northern Europe?

Tolkien had a deep and passionate love for the corpus of Old English and Old Norse poetry and prose. Embedded in that love was his fondness for the god Odin, the seeker of wisdom and the sharer of wisdom with humanity. The Norse deity appears in Tolkien’s Middle-earth as Gandalf, designed by Tolkien as an “Odinic wanderer” who wanders in and out of the story as the god does in legends of the old heroes.

Wisdom and creativity are key elements in the ancient lore’s portrayal of Odin. They are also key elements in the modern development of artificial intelligence.

Professor Chatbot

In relation to learning and teaching, things with AI have moved very quickly.

In mid-autumn of 2022, AI first began to bubble up as a subject of real concern at the university where I taught. It’s when I first realized that the small subset of sneaky students who would have been copying and pasting from Wikipedia in the past were now using chatbots to write their essays and papers for my courses.

By the early spring of 2023, enough instructors had raised concerns that the humanities faculty had an internal meeting to discuss the issue. I had assumed that the focus of the discussion would be sharing knowledge of ways to catch the offenders and enforce the school’s established code regarding plagiarism and academic honesty.

I was wrong.

![]()

The Wild Hunt is grateful for the recent support.

The Wild Hunt is very grateful to our readers for your recent financial support and amazing words of encouragement. We remain one of the most widely-read news sources within modern Paganism, and our reporters and columnists remain dedicated to a vision of journalism for and about our family of faiths.

As a reminder, this is the type of story you only see here. This is how to help:

Tax Deductible Donation | PayPal Donations | Join our Patreon

You can also help us by sharing this message on your social media.

As always, thank you for your support of The Wild Hunt!

![]()

Senior humanities faculty members plainly stated their surrender to AI. It was here to stay, they asserted, and current students would use it for the rest of their lives. The only possible response from instructors was to redesign courses so that chatbots would be used for all assignments, with professors offering suggestions on tweaking the phrasing of the prompts students would type for the chatbots to complete their assignments for them.

Part of the course redesign would be for the instructors to use AI to generate their own course materials, lectures, and assignments.

I discussed this faculty response with students in my courses on fairy tales, mythology, and religion. The response from students – none of them humanities majors, all of them some form of technology major – was almost unanimously against.

“Why should we take on student loans to submit chatbot essays in chatbot-designed courses?” one asked. “We can just save our money, stay at home, and do this ourselves.”

“This will prevent the spiritual development of humanity,” said another. “It will keep the human race from living up to its full potential.”

Undergrads can be dramatic. They can also be insightful.

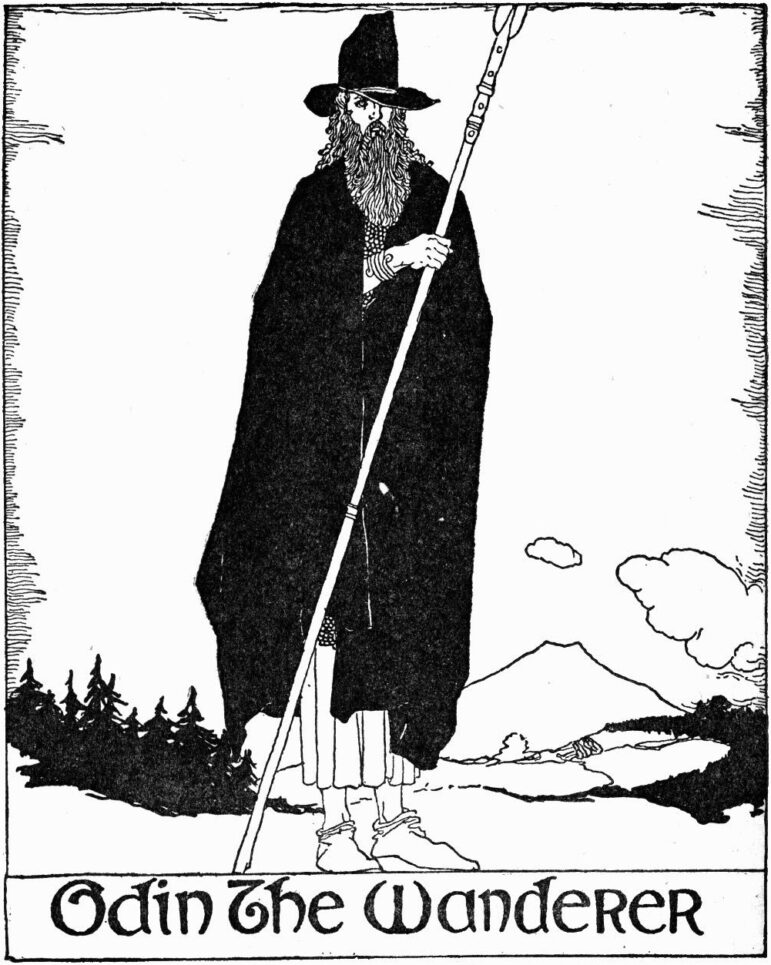

“Odin the Wanderer” by Willy Pogany (1920) [Public Domain]

During finals week of that same semester, the humanities department chairman laid off much of the dedicated teaching faculty without cause. Due to the nature of adjunct professorships, no cause was needed. Such are the ways of modern academia.

The remaining humanities faculty were handed increased course loads and increased class sizes.

Shortly thereafter, the provost sent an email to faculty that laid out “helpful resources related to the intersection of teaching and generative artificial intelligence.” It included a “guide to assigning writing and generative AI” and promised a soon-to-be released “guide on teaching and generative AI.”

The senior humanities faculty members had been right. So had the students.

AI saves bunches of money for the upper administration to bump up to themselves as bonuses for saving the money. AI saves time for downsized faculty to deal with their increased loads. AI saves time for students to breeze through their humanities courses without worrying about listening, reading, or writing.

The old line was that the university lecture is a system that transfers the professor’s notes to the student’s notes while bypassing the brains of both.

The new line is that the university course is a system that sets chatbots up to engage in dialogue with each other for institutional profit while preventing any human discourse whatsoever.

This isn’t just happening at this one Chicago school. It’s happening across the country, including at the most prestigious and most expensive institutions.

The past profit-driven move from full-time, tenured, and salaried professors to adjunct teachers paid per course without contract or benefits inevitably led to this moment in which provosts and presidents are gleefully sharpening their knives at the prospect of removing the need for any faculty members beyond basic AI administrators.

Absolutely, we should embrace advances in teaching. We should celebrate changes that enable greater participation in higher education, that better serve diverse student bodies, and that incorporate improved methods of teaching and learning.

That’s not what this is.

AI courses with AI class sessions, AI assignments, AI exams, AI essays, AI answers, and AI grading do nothing to advance teaching and learning. They do nothing to ensure the growth of wisdom.

Everyone involved – from administrators to faculty to students – knows this.

But it’s seen as inevitable, and anyone who disagrees is painted as a dumb Luddite.

The dragging down of wisdom-seeking is paralleled by a degradation of creativity.

Plagiarism machines

AI isn’t really artificial intelligence. These generative programs are just gussied up plagiarism machines.

There are a bunch of UK comics artists that I’ve been social media friends with since back in the MySpace days. They’re all around my age, and I fell in love with their work in the weekly 2000 AD and the monthly Judge Dredd Megazine back in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

I’ve collaborated with them on live music/art performances, they’ve created the cover art for my jazz and fusion albums, they’ve drawn me as a cameo character in a Judge Dredd story, and they’ve served as judges for almost all of the Midsummer and Midwinter Art Contests I’ve run at The Norse Mythology Blog for more than a decade.

They’ve also been sounding the alarm about AI for quite a while.

These aren’t technophobes, by any means. Neither am I. Many of them pencil, ink, and color their work virtually. From using a digital stylus as a pencil to using Photoshop for coloring, they’ve developed their technical skills to adapt to evolving tech. They do their work on a computer screen, and I read it on a tablet. No paper needed, #SaveATree.

These are professional artists who put in extremely long hours on extremely tight schedules. They turn written scripts into expansive visuals, and they create vast worlds that can be clearly grounded in our reality or soar free in imagined universes. They are individuals who are continually immersed in creativity.

They’re also getting ripped off.

The AI programs that create things like “Mordor Metal Fest” are trained on art created by human artists. That is to say, they steal it.

The Tolkien-inspired work is clearly stealing designs from Jackson’s films. Do the dudes who proudly prompt the programs fill out the licensing forms and pay the fees to use Jackson’s designs? As the UK artists might say, not bloody likely.

At the end of 2023, lists were leaked with the names of over 16,000 individual artists whose work was being fed into Midjourney in order to train it. In other words, these were the artists whose work was being stolen and handed over to the plagiarism machine.

Screenshots were shared that showed the company’s chief executive and developers gleefully high-fiving each other over knowingly violating copyright law while consciously feeding the artists’ works into their image generator.

The leaked list included names of many artists I know on the UK comics scene. It also included Nick Park, creator of Wallace and Gromit, along with a range of artists from Damien Hirst to illustrators of Magic the Gathering.

As of late January, UK and US artists are joining class action lawsuits against multiple AI companies. How the cases are ultimately decided could determine how many careers continue or conclude.

The repeated AI bro rejoinder to artists who speak out is that today’s prompt-writers are merely using AI to do what artists have always done – study works of the past, then create new works that mix influences together into something new.

This is patent nonsense.

The prompters do not create the AI-generated images. The actual visual output is built by computers that generate derivative works for profit by using art created by humans without acknowledgement of or compensation to the original creators. The human prompters simply give a basic command to the program in the same way that a customer gives a basic command to Alexa.

If the AI prompter is the creator of the AI-generated image, then the Alexa commander is the creator of the Amazon item that arrives at their doorstep.

The idea of being an artist without having to do any work is apparently very seductive for a great many people. For those who’ve never felt the deep pride of creating something of their very own, it’s seemingly impossible to resist typing in those little prompts, then show off the resulting images as their own creations.

Maybe more depressing is seeing people who actually have spent years and years working on their artistic craft suddenly seduced by the ease of AI image-generation. Why spend all those late nights drawing, painting, or programming when you can just fuss around a bit with prompts and get a finished work?

Why? Because the human work of creativity is what gives art its depth and heft. Because the struggle to create is what makes the creation meaningful. Because art is about expression and communication.

I’m not impressed that a bot can generate a detailed fantasy painting. I don’t care to read an AI-produced novel. I have no interest in music outputted by AI. I don’t want any of it.

If it wasn’t worth anyone’s time to create it, it sure as shooting isn’t worth my time to engage with it.

Then there are the theological issues.

There’s still time

I’ve long argued that practicing a religion, any religion, should affect how we interact with the world. It should inform our actions on a daily basis, not just when we’re actively engaged in prayer or worship.

So, I’ve been reflecting on an Ásatrú perspective on AI. Not the Ásatrú perspective. Just a possible one.

As with so many theological issues, I turn to the Old Icelandic poem Hávamál (“Sayings of the High One”). In its many verses on many subjects, Odin repeatedly returns to themes of wisdom and creativity – exactly the issues that are key to this particular discussion of AI.

Odin, god of wisdom, places great emphasis on listening with “hearing finely attuned” (in Carolyne Larrington’s translation) and on the direct exchange of knowledge:

Wise he esteems himself who knows how to question

and how to answer as well.

A focus on exchange and reciprocal gifting is key to the old religion and to modern Ásatrú. In lines that we use during the fire offering portion of the celebratory gatherings of Thor’s Oak Kindred, Odin states,

Mutual givers and receivers are friends for longest,

if the friendship keeps going well.

Odin returns repeatedly to the theme of mutuality and explicitly ties it to teaching and learning:

One brand takes fire from another, until it is consumed,

a flame’s kindled by flame;

one man becomes clever by talking with another,

but foolish through being reserved.

The way to become wise, according to the wisdom-seeking and wisdom-sharing god, is to engage in dialogue:

Asking and answering every wise man should do,

he who wants to be reputed intelligent.

By embracing and instituting AI-generated courses, university administrators are going directly against everything Odin teaches. In pursuit of profit, they are throwing away foundational relational ways of learning.

I love Odin as the wise wizard obsessed with gathering and sharing wisdom. As both longtime teacher and lifelong learner, I’m drawn to him as an avatar of education.

As a practitioner of Ásatrú, I can’t support institutions that deride and destroy the relationships between teachers and students.

An illustration of Odin in the flames by Willy Pogany (1920) [Public Domain]

Odin, god of creativity, testifies to the struggle and sacrifice inherent to expressing inspiration.

He describes how he “risked his head” in order to bring the mystical Mead of Poetry to “men’s sanctuaries,” where it fills all who imbibe it with creativity as a beverage that represents the intoxication of inspiration in physical form.

He also recites the famous tale of his self-hanging:

I know that I hung on a windswept tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.With no bread did they refresh me nor a drink from a horn,

downwards I peered;

I took up the runes, screaming I took them,

then I fell back from there.

On the mystical level, the god Odin hangs for nine nights (a magical number) on the World Tree (a magical location) wounded with his spear (a magical object), suffering with a self-inflicted wound and undergoing lonely self-deprivation in order to bring back the runes (magical symbols, at least in this context) from a terrifying and mysterious place in order to share them with humanity.

It’s not difficult to transfer this down to our mundane world and see it as a portrayal of the individual artist working through the night at her desk, suffering cramps from endless detailing, eschewing company and comfort while striving to complete a commission by a given deadline, pull a newly-created work of art from that weird world where new ideas come into being, and share it with her audience.

By stealing the work of creative artists as fodder for their profit-driven plagiarism machines, AI companies defecate upon the very act of creativity that Odin so lionizes.

I love Odin as the mystical inspirer of creativity. As both musician and writer, I’m drawn to him as an embodiment of the creative force.

As a practitioner of Ásatrú, I can’t support companies that steal the work of human artists to generate disposable dross.

Not everyone embraces the wizardly and inspirational aspects of Odin as I do. Some are repulsed by a character whose harmful aspects they can’t get past.

Tolkien split Odin in two, giving his beneficial characteristics to Gandalf and his frightening ones to Sauron. I’ve loved Gandalf since first meeting him in the 1977 Rankin/Bass cartoon of The Hobbit, and I’ve loved Odin since meeting him in the 1920 Padraic Colum retelling of Norse mythology titled The Children of Odin.

I fully acknowledge that Odin does harm, but I also counter that his harmful deeds are done for the benefit of the divine and human worlds.

AI does harm to teachers and students. It does harm to artists, writers, designers, and creatives of all types. It also steals the faces of the dead (like Christopher Lee in the “Mordor Metal Fest”) and the bodies of the living (like Taylor Swift in the recent AI-generated pornography disaster). What is the benefit, beyond mindless amusement and crass profit?

As a practitioner of Ásatrú, I won’t use AI. I won’t share its output.

What I will do is raise a drinking horn to Odin, pray for the failure of AI in all its forms, and support humans who do the real work and bring so much joy to all of us.

AI is not inevitable. We can simply decide it’s wrong and turn away from it. If we don’t use it, then it doesn’t make a profit, and the companies will dry up.

As Odin declares,

I was young once, I travelled alone,

then I found myself going astray;

rich I thought myself when I met someone else,

for man is the joy of man.

And as the singer sings,

Yes, there are two paths you can go by, but in the long run

There’s still time to change the road you’re on.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.