AMSTERDAM – While the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine has resulted in the Russian destruction of churches, cathedrals, museums, and libraries from bombings, burnings, and shelling, the earlier Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 resulted in the plunder of paintings, artwork, and antiquities by Russia. Now a Dutch court has ruled that some objects that have been on loan from Crimean Museums for 9 years in Amsterdam are to be returned to the rightful owner: Ukraine.

However, there is an important and additional piece to the case: Russian attacks have targeted the national heritage of Ukraine. Two years ago, Ukraine’s Minister for Culture Oleksandr Tkachenko noted consistently that Russian forces have vandalized and targeted artwork and institutions that are part of Ukraine’s cultural roots.

Tkachenko has previously remarked, “It’s not only about Ukrainian people [in terms of] human lives [lost] and territory, it’s also about our identity, our culture and our heritage. As soon as Putin and his regime deny the identity of Ukrainians, they’re trying to ruin everything that’s connected to cultural heritage.”

Now, the ancient Scythian artifacts that were on loan to Amsterdam’s Allard Pierson Museum from museums in Russian-occupied Crimea. The dispute arose after Russian troops seized and annexed Crimea in 2014, with both Ukraine and museums in Moscow-controlled territory claiming ownership. Russia argued they were part of their collection because Crimea is part of Russia in the legal dispute over ownership rights of the artifacts.

The Dutch Supreme Court disagreed. The return comes after the High Court ruled in June that the artifacts should be returned to Ukraine. Kyiv considers them part of its national heritage, while Moscow-controlled museums argued for their return to the peninsula based on loan terms. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov insisted the artifacts “belong to Crimea and should be there.” The Moscow-installed governor of Crimea suggested their return should align with the “goals of the special military operation,” referencing Russia’s official title for its war in Ukraine. Ukrainian customs services reported that a truck carrying the artifacts entered the 980-year-old Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra monastery complex for further identification.

A buckle in the form of a Hercules knot – one of the treasures returned to Ukraine. Image via Allard Pierson Museum

As for the objects themselves, the artifacts include a solid gold Scythian helmet and a golden neck ornament, which spent nearly a decade in the Netherlands. The items, dating from the 7th to 3rd centuries BC, were part of the exhibition ‘Crimea: Gold and Secrets of the Black Sea.’ After almost 10 years of court hearings, the National Museum of History of Ukraine announced that 565 artifacts, including ancient sculptures, Scythian and Sarmatian jewelry, and Chinese lacquer boxes, had been returned by the Allard Pierson Museum. The collection will be stored in Kyiv until the de-occupation of Crimea.

The Scythians were nomadic people who inhabited the central Eurasian steppes from around the 9th century BCE to the 4th century CE. Their territory extended from the northern Black Sea across the Caucasus, into Central Asia, and as far as the borders of China. The Scythians were known for their skilled horsemanship, archery, and their distinctive art and burial practices. The Greek historian Herodotus carefully detailed and described their customs, society, and interactions with neighboring cultures.

Scythians had a nomadic lifestyle, meaning they did not have permanent settlements and regularly moved with their herds of livestock, especially horses. This lifestyle was well-suited to the vast grasslands of the Eurasian steppes. Despite their lifestyle, the Scythians had a hierarchical social structure with a warrior elite at the top. They were organized into tribes or clans, each led by a chief or king. The importance of the warrior class is evident in both their social structure and their emphasis on martial prowess and they were known in the ancient world as skilled warriors, known for their horse archery and proficiency in using the bow and arrow. They often fought from horseback, allowing for greater mobility on the open steppes.

More importantly, Scythian art is known for its animal motifs and intricate goldwork. They created beautiful objects, including jewelry, weapons, and horse trappings, often featuring depictions of animals, mythical creatures, and scenes from daily life.

In addition, the Scythia burial practices ensure that much of their artwork would not be lost to history. One of the most notable aspects of Scythian culture is their elaborate burial practices. Richly furnished burial mounds or kurgans were created for their elite members, containing not only the remains of the deceased but also various goods such as weapons, jewelry, and even sacrificed animals.

The Sarmatians were a group of ancient Iranian-speaking nomadic peoples who inhabited the vast Eurasian steppe from the 5th century BCE to the 4th century CE. They were known for their formidable skills in mounted warfare and played a significant role in the complex interactions between settled civilizations and nomadic groups during antiquity.

The Sarmations shared the nomadic lifestyle of the Scythians and their structure. They moved with their herds across the steppes, adapting to the seasonal changes and seeking pasture for their animals. The Sarmatians were skilled warriors, particularly known for their expertise in mounted archery. They were often employed as mercenaries and played a role in various conflicts throughout the ancient world. Their military skills and reputation as fierce horsemen made them formidable adversaries.

The Sarmatians had a distinctive material culture that included unique artistic expressions, such as intricate metalwork and designs on clothing. Archaeological evidence, including burial sites and artifacts, provides insights into their customs and lifestyle. One notable aspect of Sarmatian society is the presence of women warriors. Ancient accounts suggest that Sarmatian women participated in warfare alongside men. Archaeological discoveries, such as graves containing female skeletons with weapons, support these accounts.

The Sarmatians interacted with the Roman Empire, and at times, they were allies or adversaries. They were involved in several conflicts along the Roman frontiers, and some Sarmatian groups served as mercenaries in the Roman military. However, despite those interactions, there is a lack of a written record from the Sarmatians themselves means that much of our knowledge about them is derived from external accounts and archaeological findings.

Tacitus, a Roman historian and politician who lived in the 1st century AD, wrote about the Sarmatians in his work “Germania.” In this ethnographic work, Tacitus provides a brief description of various Germanic and non-Germanic tribes, including the Sarmatians. The Sarmatians were a group of Iranian nomads who inhabited the vast Eurasian steppes.

Tacitus mentioned that the Sarmatians were a fierce and nomadic people known for their skill in horsemanship and warfare. He described their lifestyle, including their reliance on horseback riding and their use of a type of saddle that allowed them to easily maneuver and shoot arrows while mounted. Additionally, Tacitus noted the Sarmatians’ social structure, emphasizing the importance of their warrior elite and their nomadic way of life.

Still, Tacitus’s accounts were not entirely accurate: much of his writings contained second-hand information.

Unlike the Scythians, some environmental changes and the rise of powers in late antiquity, Sarmatian groups declined after the 4th Century CE and were assimilated into other cultures, while others disappeared from historical records.

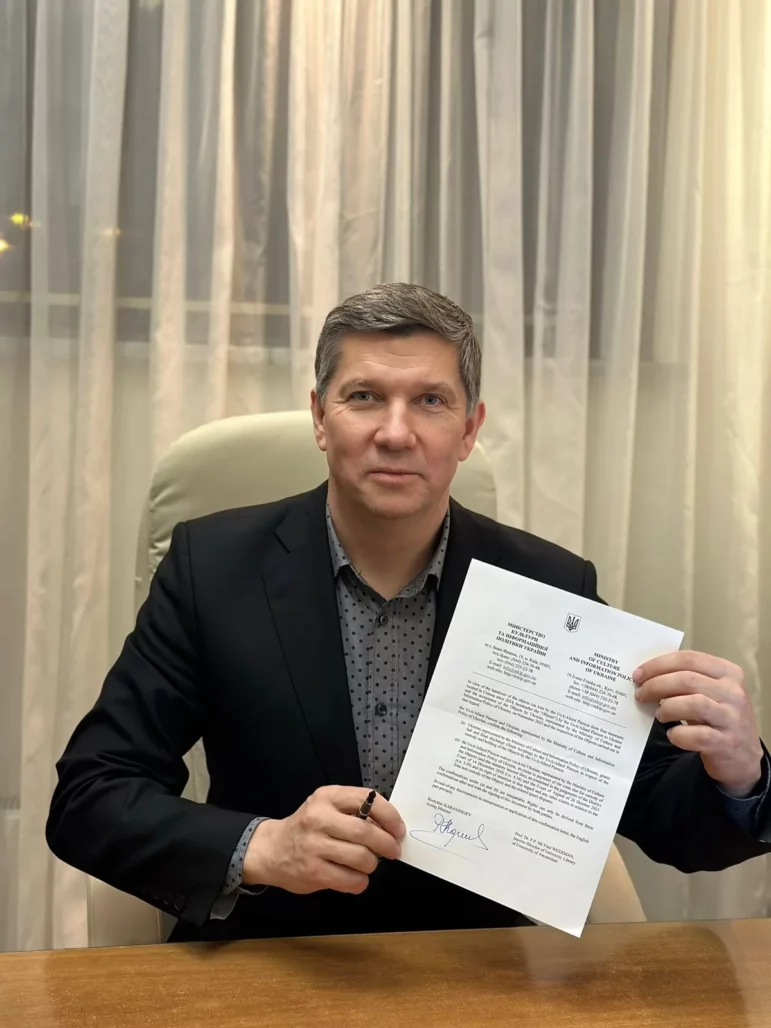

Mr. Rostyslav Karandeev, Ukraine’s acting culture minister signing the return agreement for the objects. Via Ukraine Government

Rostyslav Karandeev, Ukraine’s current acting culture minister, announced the return of the objects 5 days ago. “The return of artifacts of special historical and cultural significance is a significant and multifaceted process. It combines legal, museum, diplomatic and logistical aspects. We are looking forward to the return of the collections, one of which is known as “Scythian gold”, back home to Ukraine,” said Rostislav Karandeev.

Dmitry S. Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman, said yesterday that the objects belong “to Crimea and must be there,” during a news conference, according to Interfax, a Russian news agency.

For its part, the Allard Pierson Museum agreed not to charge Ukraine for the previous nine years of storage, security, and climate control costs. Ukraine covered some moving costs.

It is not clear where the artifacts will be held in Ukraine, though reports confirm they have arrived. Reuters reported that “Ukrainian customs services reported on Monday that a truck carrying “2,694 kg of cultural property” entered the 980-year-old Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra monastery complex, where a further identification process would take place.”

The objects will then remain at the Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine in Kyiv.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.