It’s no secret at this point that everyone wants to have sex with the devil.

It’s a selling point, a mainstay of the brand – and certainly one of the defining religious characteristics of the modern day. From the famously erotic Le génie du mal, to The VVitch’s Black Phillip and his historical antecedents in the witch trial records, to the modern Man in Black – it seems like history is united in figuring the devil as immensely alluring, mysterious, dark, and more than willing to fill his followers with surging, pulsing, ecstatic power.

This is such a non-statement that it is, at this point, much harder to find a depiction where the devil is anything less than a caricature of the most erotically charged image available to the imagination of the creator.

There’s just one problem: nobody can tell me who the devil is.

Maxim models dressed as the devil for Maxim’s Hot 100 Celebration in Sydney, Australia, 2012 [Eva Rinaldi, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

Or rather, the instant that I ask the question things start to break down.

For instance – in high school I was, as an already-confirmed incurable nerd, a big fan of the actor Thomas Mitchell. I’d seen him first as Doc Boone in Stagecoach, and then again as Uncle Billy in It’s a Wonderful Life, and if I hadn’t quite made it my mission to watch every black-and-white movie in the library I was at least going to watch everything I could find with Mitchell in it.

That’s how I came across The Devil and Daniel Webster, a very odd little film from 1941 in which Mitchell plays the non-devil title character. If my Kansas education had not prepared me for the political and social commentary on a lawyer from 1800, my conservative Christian upbringing had left me even less prepared for his antagonist, Mr. Scratch.

The premise of the movie, and of the short story that inspired it, is that Webster is called in for a court case in which his client has sold his soul to the devil. I was familiar with the idea – I had been taught that acquiring souls was the main pursuit and mission in the devil’s book. But the figure in the movie wasn’t the almost-Manichean figure I had internalized, an Adversary responsible for every doubt and hesitation that troubled any good Christian.

Instead he was a charming, underhanded swindler who was bound by the letter – if not the spirit – of every agreement. I was immediately fascinated by his laughing, magical intrusion into a film that – with apologies to Mr. Mitchell – I otherwise found very boring. I knew that the devil was a liar and a thief, but by the end of the film I was convinced it was Mr. Scratch who had been tricked out of his fair share of a bargain.

It opened a whole new fascination for me. By the time college came around I would, at the least provocation, go into a small but polished explanation of the difference between “the devil” and “the American Folkloric Devil.” The figure who appeared at crossroads and made carefully-worded deals that traded souls for musical gifts, or money, or the dearest wish of someone’s heart was a tradition in itself, I’d explain. It didn’t really have much to do with Christianity – in a lot of ways these stories reminded me more of Yeats – and the clever lads that challenged this devil and won never called upon the angels to do it.

This was all about wits, and wordplay, and sick guitar solos – or, in some cases, pure dumb luck. The souls at stake were more the ante in a game than any sort of spiritual truth in themselves. Lucifer was an entirely different thing.

Devil representation in the Žmuidzinavičius Museum in Kaunas [Usien, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

The punchline – which continues to be a punchline in every new name and avenue that I stumble upon 20 years later – is that they are all different things.

Looking into Biblical scholarship about Lucifer led me to a questionable Latin translation referring to the planet Venus. Digging further into the modern Christian idea of the figure dead ends, as so many other modern “Biblical” studies do, in Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Inferno. The story of the fallen angel who had, through pride or vanity, rebelled against heaven stopped alongside Dore’s pinups.

The word “devil” itself was a similar lost thread, spiraling back to Ancient Greek roots that vaguely meant “slanderer” – less a name than a description. It wasn’t until I researched Satan that I found the figure I had learned about in church, the “accuser” who wandered the earth tempting Jesus and prodding God to torture Job. But he was missing most of the characteristics I associated with the devil by that point. Temptation he had in spades, and disease, but those were his main characteristics. He was, with few exceptions, simply the bad guy when one was required by the text.

It was a stretch of the imagination to connect Satan – a spirit big enough that God would engage in a wager – with the broody blonde who headlined Vertigo comics. It was even harder to connect either of them with the small-time con who lost a court case judged by Benedict Arnold.

Once that broke down, the pieces of the devil kept falling away, revealing new origins. Here were Pan’s goat legs and curly hair; there were the blue eyes and bad deals of Charles Hatfield. There were plenty of people who were called “the devil,” sure – but most of them had names. They were specific and unique characters. There were any number of people who had been lumped into the title. They’d picked up family resemblances along the way – a set of horns here, a pointed tail there – but their backgrounds, their modus operandi, even their goals were different.

The only link I could identify with any real certainty was that they were the bad guys – whatever that meant. They were scary. They operated not just outside but against the status quo. Whatever the ‘good’ was for, they were against – and it followed that an awful lot of them were hotter than Hell.

I’ll be the first to admit that my young fascination with Walter Huston’s Mr. Scratch was not exactly a universal experience. But Elizabeth Hurley had her turn as the devil at about the time I was loading Daniel Webster into my VCR. Even in stories where the devil is downright monstrous, they leverage sex as temptation and goad, driving their intended victims into traps of their own devising. Sex is their promise and their punishment, encoded in the animalistic elements of their bodies and the blatant appeal of the temptresses in their cohorts – and it took me years to question why.

Of course they used sex as a temptation. That’s what bad people did.

It was a simple premise. When I got up the nerve to suggest that maybe sex could be good, actually, the premise dissolved and took the entire category – the entire concept of a devil – with it.

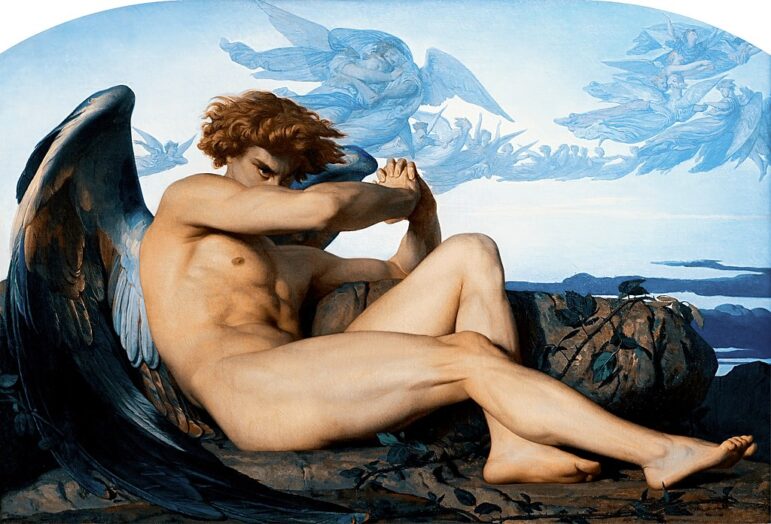

Alexandre Cabanel, The Fallen Angel (1847). Oil on canvas, 121 x 190 cm (47.6 x 74.8 in). Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France [public domain]

The common thread, if there was one, was temptation.

Being tempted meant being pulled away from something – and suddenly, I was aware that I had been defining the devil by what they weren’t. If they used money, sex, and power to tempt people away from the “good path,” then it followed that ‘good’ was a humble, chaste, and ascetic way forward. Even in narratives that did not feature the Church or its attendant spirits, understanding these characters as “evil” centered Christian understandings. Years after I had left the Church myself, I realized that a huge part of my paradigm still featured it, hidden in a concept as foundational as the idea of “good.” Even in my own, third, path, I was defining myself by the Christian I was not.

The stories I had gathered of crossroads deals and fallen stars took on a new life. What if it would be alright to leave a situation that brought me no joy and do something that I loved instead? What if the road called and I answered, banjo on my back and heart full of song?

What if I rebelled against a system that betrayed me – and I was right to do so? What if the people who were chaste and ascetic were not necessarily more moral than me? What if they were just different, and morality could be defined some other way?

Sin was a Christian idea. What did I believe?

The devil asks a lot of questions. For the first time, I let myself enjoy the answers.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.