Following our first Pagan pit-stop in Hønefoss, my wife, my kid, and I drove south towards the old county of Vestfold where some friends of ours recently moved. Encompassing the coast to the southwest of Oslo, Vestfold is a district characterized by its maritime history, a history that stretches all the way back to the Viking Age. Some of the most notable artifacts from that ancient time were found here, such as the famous Gokstad and Oseberg longships to name but two. I was therefore very much looking forward to explore the countryside and visit some of the local sights.

Our first stop was Larvik, where Synøve and her boyfriend had bought a small apartment in the outskirts of the town. I had been to Larvik once many years back, but only for a few hours, waiting downtown for the train, so I was completely unfamiliar with this neighborhood. Located not far from the highway on one side and a thick, hilly forest on the other, the placid neighborhood seemed like the ideal place from which to launch our various expeditions. These, however, would have to wait: with a nap-less and hungry toddler in tow, the rest of the day would have to be dedicated on more basic chores.

Half a tub of yogurt and a quarter of a watermelon later, the small one was finally in bed, happily snoring. This is when I finally get the chance to ask Synøve, whose family comes from the neighboring countryside, whether she know of any heritage sites worth investigating.

“Well, there’s some old graves near an ancient stone church I know,” she says, “and this stone-monument not far from there. We could try to make it there tomorrow if you want.” It only took her a minute, and I was sold already. I knew this was going to be good.

The medieval church of Hedrum in Vestfold. Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

The following day, after taking an impromptu tour of Larvik’s city-center to check out the local maritime museum, Synøve, my wife, my kid and I set off to the countryside towards our first destination: the old church of Hedrum. Hedrum, or, as it would have been called back in the day, Heiðarheimr (“bright-” or “heath-home”) was actually one of the very first church sites in Norway during the Viking Age. The first church was named already around the year 1080, and the existing structure, a modest stone building in Romanesque style, was likely conceived in the 12th century.

As was often the case in those days, the church in Hedrum was built here because the area had been an important power center for centuries. Located just a few miles north of Kaupang, Norway’s largest Viking Age trading center, the archeological complex in Hedrum includes everything from a longhouse, boat graves, elite imported wares and over 20 grave mounds. However, archeological digs indicate that this settlement probably ceased to exist sometime in the mid-11th century, when the first church was likely established.

Nowadays, little is left of this ancient settlement besides the grave mounds, which, fittingly enough, are located just behind the graveyard. As we park the car by the side of the church, my daughter zooms out of the vehicle, heading towards the mounds. She likes the little sinuous paths that have emerged in between the grassy knolls and starts collecting fallen leaves.

Two of the twenty Iron Age mounds located just outside the Hedrum medieval church in Vestfold. Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

Confident that my girl won’t bother the mound-dwellers, I head towards the church building. The ruddy tower on the western side of the building stands tall under the scorching southern Norwegian heat, casting a shadow towards its older stony walls. Inside the church, I am met with the coolness and dusty-smell so characteristic of medieval buildings.

By the altar, a group of church ladies are rehearsing some hymns under the watchful eye of the organist. I spot a large coffee-table book on a table nearby: it’s a history of the church and the surrounding local area. The organist, noticing my interest and now free from his musical duties, starts a conversation, which quickly results in me receiving the book in question as a gift. I thank him profusely, promising that I will make good use of it (while leaving out the fact that this will be for a Pagan news outlet).

Leaving the church just in time to miss the mass, we start driving towards the stone monument Synøve mentioned earlier. Acting as a navigator, she takes us towards increasingly diminutive roads tucked in between golden fields and green woods.

At one point, she tells us to stop in between two farms. “My grandfather used to live in the one on the left when he was young,” she says, “and my grandmother was from the one across the field on the right. They just basically knew each others since they were kids, and later married, in the Hedrum church even, if I ever recall correctly!”

Talk about a private tour! This is not the kind of guiding you would get from booking an excursion through Tripadvisor, I can tell you.

Soon after passing Synøve’s grandparents’ farms, we reach a gravel road just wide enough for our small rented Toyota to fit in. A minute in, the roads abruptly stops, right by the edge of a small pine and birch forest. As we step out, my daughter takes a few steps in and immediately exclaims, in her characteristic mixture of Swedish, Norwegian, and French: “Look dad! Big rocks! Come and seeeeeeee!”

The main stone ship outline in Istrehågan. Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

The rocks were indeed big, and numerous: 18 monoliths forming the main ship-like outline, alongside a similar but smaller structure, and three modest stone circles. This is Istrehågan, a little information panel informs me, Norway’s largest prehistorical stone monument.

Although shorter than the Ale’s stones we visited last summer, the main ship outline’s stern and bow stones are significantly taller, at over 4 meters high (11 feet). While those are certainly impressive, my daughter is most interested in the smaller, flatter stones on the edge of it. As I begin to inspect the “ship,” she runs back to the woods, grabs a small and stubby branch, and puts it on the top of the stone. When I am done looking and photographing the other structures, the number of sticks has multiplied and a bunch of leaves have been added for good measure.

“It’s good food dad. Do you want to eat?” she kindly asks, only for me to politely decline.

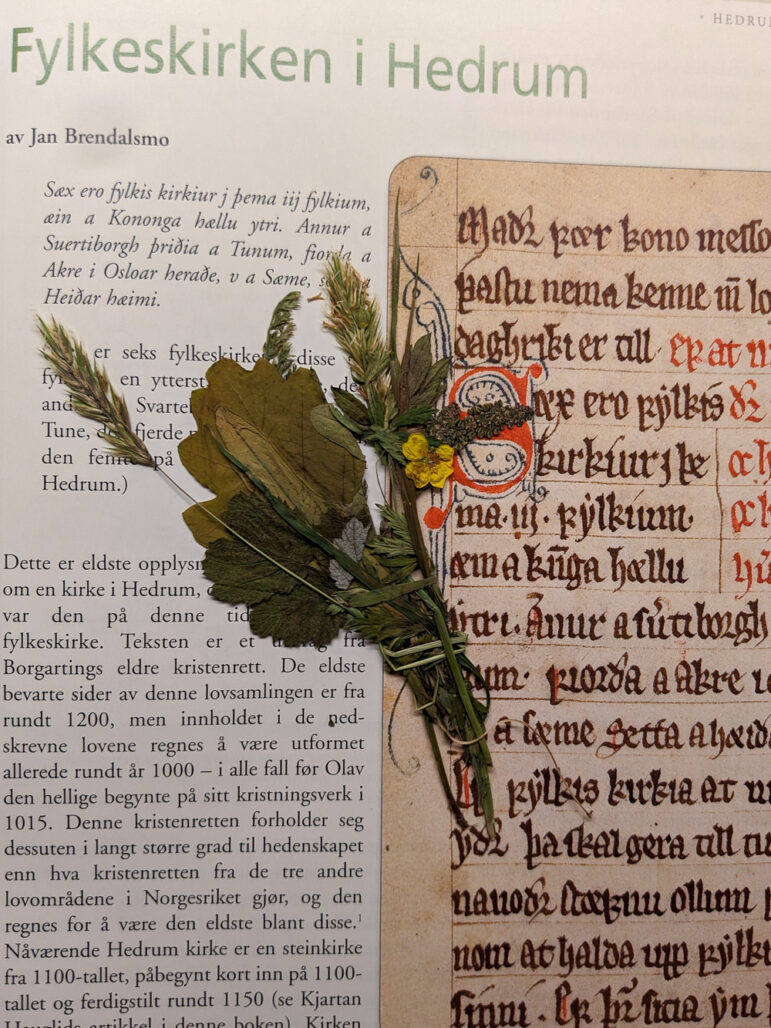

Instead, I head back inside the ship, where green grass and flowers abound, and I start gathering a small bouquet as a memento, like I did last year on the site of the old temple at Uppåkra. True, Istrehågan never was a temple, but, located within earshot of an exceptionally dense network of Iron Age archeological sites, it likely occupied a central place for the local community long before the advent of the Viking Age.

The small ship outline in Istrehågan. Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

With burial finds dated from the sixth to the mid-11th century C.E., Istrehågan probably saw its fair share of Pagan rituals before the new religion took hold. Further underscoring the sacral quality of the area are places like the old Vestad farm, just two hundred yards from the stone circles, whose name literally means “sacred place,” or the enigmatic Bronze-Age stone carvings at Haugen a mile further north (a site I hope be able to visit one day soon).

Even after one thousand years of Christian influence and spiritual control, the wealth of ancient religious heritage sites found in this small stretch of countryside acts as a witness to the resilience of the Old Religion. When the faith ceased to be (at least publicly), the achievements of its followers, the sanctified spaces they built, and the communities they established, endured.

One of the smaller circular monuments in Istrehågan Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

Here at Istrehågan, rituals in the name of the old gods might not take place anymore, but that does not stop people from enjoying the space. As I look past the ship’s stones, I spot an elderly couple absorbed by the view, a guy walking his tiny little dog and a spandex-wearing woman darting out of the wooden path, sprinting like there is no tomorrow. The sun is shining, a warm breeze rustles through the foliage. A intense feeling of peace, harmony, and timelessness emanates from the clearing. “A sanctuary,” I whisper, as I head back.

A small bouquet of herbs and flowers gathered atop the Istreågan stone ship, placed on the top of the Hedrum church history book. Picture by Lyonel Perabo (2023)

“Did you enjoy this, girl?” I ask my daughter, still ecstatic from her stick-collecting project.

“Yeeeees! I like big rocks! I want to see more! And I want to have ice-cream!” She candidly answers.

“We’ll see if we can find more rocks later, kiddo, but I’m sure we can find ice-cream first,” I answer, already planning the drive to the nearby gas station, and the closest prehistoric grave-mounds. Truly, Vestfold is a hell of a place for a summer vacation.

This story will be followed next month by another article focusing on yet further sites visited by the author in the county of Vestfold.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.