We constantly tell myths to each other and to ourselves. Our tales are not always part of the high mythology of deities and demigods. Often, they are about elements of our daily lives. Sometimes, they are about sports.

As we perform the enchantment of mythicization on our world, we lift people, places, and things from the mundane to the meaningful. The trivial becomes tremendous and the ephemeral becomes enduring.

This mythifying process can have profound effects that reach out to affect subsequent generations. Myth, regardless of veracity, can have more power than any truth.

This power is not always used for positive ends.

Democracy vs. fascism

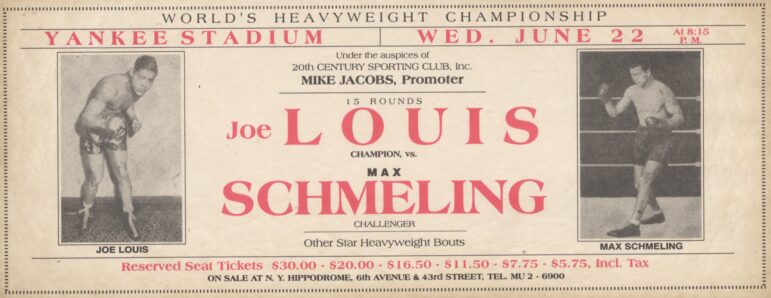

In 1938, Joe Louis was 24 years old, the undisputed heavyweight boxing champion of the world, and determined to avenge the lone loss on his professional record. Two years earlier, before Louis won the championship from “Cinderella Man” James J. Braddock, the German Max Schmeling had knocked him out in the twelfth round.

Advertisement for Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling rematch (1938) [Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture]

At a time when boxing was an enormous worldwide sport that was taken extremely seriously by a vast number of people, African-Americans felt Louis’s defeat as a massive blow, and Germans (including Adolf Hitler himself) saw Schmeling’s victory as a sign of Teutonic superiority. The rematch took on plainly mythical proportions.

In the build-up to the second bout, Louis was cast by American media and fans as the shining paragon of U.S. democracy, while Schmeling was denigrated as the dark representative of Third Reich fascism. In Germany, the Nazi regime’s propagandists promoted Schmeling as the Aryan powerhouse who would again demolish the non-white American as a victory for Germany.

In addition to the 800,000 in attendance at Yankee Stadium for the second fight, 70 million were glued to their radios in the United States while over 100 million listened around the world. Today, when so many people have forgotten about boxing, it’s amazing to see how much weight the world placed on this sporting event of two contestants – two men seen as mythic figures representing their races, their nations, and their political systems in the time just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

The fight itself was not competitive. Schmeling shockingly let out a chilling scream when Louis’ punches shattered two of his vertebrae. The American champion won by technical knockout only two minutes and four seconds into the first round, as referee Arthur Donovan saved the German from the unstoppable assault. Schmeling had only managed to throw two punches in the contest.

The mythic reverberations echoed around the world. Louis was hailed as a hero of democracy and became a uniformed propaganda presence rallying Americans at home and American soldiers abroad. Louis was shut out by the Nazi regime and pushed into combat as a German paratrooper.

“Save me, Joe Louis!”

The myth of the superheroic Louis became so large that a story now known to be fictional circulated even through the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Back in the 1930s, the story goes, a black convict was being executed in a Deep South gas chamber. As he breathed his final, poisoned breaths, he called out, “Save me, Joe Louis! Save me, Joe Louis!” As his life faded, he openly prayed that the great African-American boxer would smash through the walls like (then newly-created) Superman to rescue him from death.

In his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, King presented the tale as true, writing:

In a few words the dying man had written a social commentary. Not God, not government, not charitably minded white men, but a Negro who was the world’s most expert fighter, in this last extremity, was the last hope.

But the tale wasn’t true. Allen Foster, age 19, was the first to die in North Carolina’s freshly fabricated gas chamber. He was convicted of raping a white woman a knifepoint – a conviction based on her testimony and a confession that he said was beaten out of him with clubs.

He didn’t call on Joe Louis during his 1936 execution, but he did die painfully and horrifically. Before his death, he told reporters that he had sparred with Joe Louis – a story that doesn’t mesh with the boxer’s documented dates and locales. Foster’s mother said her son was “half-crazy.” Within a month of Foster’s death, the myth of the Louis prayer was appearing in newspapers.

Likewise, the myth of Louis as the embodiment of American democracy defeating Schmeling as the manifestation of German fascism also doesn’t quite work. After spending the war donating $90,000 (over $1.5 million today) of his fight purses to the war effort, Louis was endlessly hounded by the IRS for back taxes on the earnings he never saw. Chased into insolvency by the same government he had so fully supported during the war, Louis tried to make ends meet by working as a wrestler and as a greeter at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.

The myth of Schmeling as the face of fascism portrayed by the media on both sides also isn’t quite right. During his fight career, he had stuck with his American Jewish manager Joe Jacobs (against the wishes of German leadership), refused to join the Nazi Party, and helped save a pair of Jewish children from Nazi arrest and murder in Berlin. After the war he hooked up with the American multinational Coca-Cola corporation, who made him the face of their German franchise, a company executive, and owner of a bottling plant.

Louis, the supposed force for freedom who was relentlessly soaked by his own government, eventually received financial help from Coca-Cola baron Schmeling, the supposed force for fascism and his old opponent.

Does the fact that the myths were not true erase their value as myths?

The power of propaganda

As a kid, I used to listen for hours to vintage radio shows on Chuck Schaden’s Those Were the Days on WNIB 97.1 FM Chicago, which was then the Second City’s second classical music station. I was such a fan of “old-time radio” that I subscribed to Chuck Schaden’s Nostalgia Digest and Radio Guide (actually printed and mailed out in those pre-internet days) and read multiple biographies of Jack Benny and Fred Allen from the public library.

I also obsessed over the origins of DC and Marvel superheroes and supervillains, likewise devouring any collection I could find at the library. Marvel characters were mostly creatures of the 1960s (aside from Timely Comics holdovers like Captain America and the Human Torch), but DC stars such as Superman, Batman, the Flash, Green Lantern, and Wonder Woman all made their debuts during the early years of Joe Louis’s reign as heavyweight champion.

Between the radio shows and the comic books, I was a child of the 1970s and 1980s inundated with American propaganda of the late 1930s and early 1940s. From Jack Benny to Captain Marvel (the “Shazam!” one, not the MCU one), public figures – real and unreal, in and out of character – hawked war bonds, promoted the Allied cause, and denigrated the Axis powers.

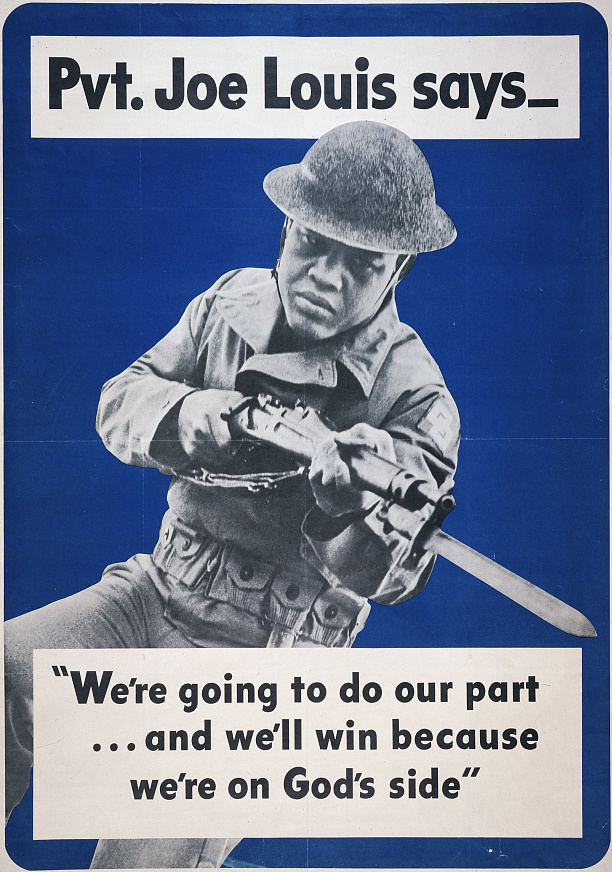

So, I understand at least a bit of what Joe Louis speaking out for the war effort, visiting troops on the front, and publicly donating his purses to help U.S. forces may have meant to Americans at the time. He was a superhero in real life, the unstoppable “Brown Bomber” who famously declared, “We’re going to do our part, and we’ll win, because we’re on God’s side.” He was the top athlete on the planet, and he was standing with us against evil forces.

Joe Louis on a U.S. Government Printing Office poster (1942) [Library of Congress]

It’s all propaganda, of course, and propaganda is designed to bypass the intellect and manipulate the emotions. For a kid, those old shows and comics seemed to portray a nation of people unified by a righteous cause, sacrificing of themselves and working together to defeat a terrifying and totally evil enemy. For an adult, it’s not so simple.

It wasn’t until decades later that I learned how many Americans supported Hitler up until the point that the U.S. joined the war. The German-American Bund was created in 1936 to promote Nazism here and build an American Nazi movement. Its events across the country drew massive numbers. The propaganda use of radio, comics, and sports created a myth of unity designed to build that same unity in actuality.

Humans, however, are unified by nothing more than an common enemy. The imagery of the day – especially in comics and cartoons – featured insanely murderous Germans and frankly disgusting caricatures of Japanese people. The process of propagandistic mythicization is also one of plain dehumanization. It doesn’t take much for a righteous cause to descend into unrighteous slander.

Then again, there is the case of the convict in the gas chamber calling on Joe Louis.

“A scream of joy”

We know that the “Save me, Joe Louis!” story is a fabrication, a created modern myth with elements we can trace and an evolution we can follow. Yet, it expresses a truth in a way that transcends simple factuality.

In her 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Maya Angelou writes of reactions to the radio broadcast when Louis was temporarily in trouble while defending his title during a 1935 fight with Primo Carnera, the Italian giant who was seen as a stand-in for the fascist Mussolini:

My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. It was a white woman slapping her maid for being forgetful.

The men in the Store stood away from the walls and at attention. Women greedily clutched the babes on their laps while on the porch the shufflings and smiles, flirtings and pinching of a few minutes before were gone. This might be the end of the world. If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.

After Louis turns it around and knocks out Carnera, the tone is distinctly different.

Champion of the world. A Black boy. Some Black mother’s son. He was the strongest man in the world. People drank Coca-Colas like ambrosia and ate candy bars like Christmas. Some of the men went behind the Store and poured white lightning in their soft-drink bottles, and a few of the bigger boys followed them. Those who were not chased away came back blowing their breath in front of themselves like proud smokers.

It would take an hour or more before the people would leave the Store and head for home. Those who lived too far had made arrangements to stay in town. It wouldn’t do for a Black man and his family to be caught on a lonely country road on a night when Joe Louis had proved that we were the strongest people in the world.

Yes, people take sports seriously and in a mythic mode. If the fight with the somewhat hapless Carnera had such an outsized reaction in a rural African-American community listening from far away, the joyous aftermath in New York City itself to the victory over Schmeling was like an explosion of jubilation.

Richard Wright reported on the scene in an article published less than two weeks after the fight:

In Harlem, that area of a few square blocks in upper Manhattan where a quarter of a million Negroes are forced to live through an elaborate connivance among landlords, merchants, and politicians, a hundred thousand black people surged out of taprooms, flats, restaurants, and filled the streets and sidewalks like the Mississippi River overflowing in flood time. With their faces to the night sky, they filled their lungs with air and let out a scream of joy that it seemed would never end, and a scream that seemed to come from untold reserves of strength.

They wanted to make noise comparable to the happiness bubbling in their hearts, but they were poor and had nothing. So they went to the garbage pails and got tin cans; they went to their kitchens and got tin pots, pans, washboards, wooden boxes, and took possession of the streets. They shouted, sang, laughed, yelled, blew paper horns, clasped hands, and formed weaving snake-lines, whistled, sounded sirens, and honked auto horns. From the windows of the tall, dreary tenements torn scraps of newspaper floated down. With the reiteration that evoked a hypnotic atmosphere, they chanted with eyes half-closed, heads lilting in unison, legs and shoulders moving and touching:

“Ain’t you glad? Ain’t you glad?”

Knowing full well the political effect of Louis’ victory on the popular mind the world over, thousands yelled:

“Heil Louis!”

It was Harlem’s mocking taunt to fascist Hitler’s boast of the superiority of “Aryans” over other races. And they ridiculed the Nazi salute of the outstretched palm by throwing up their own dark ones to show how little they feared and thought of the humbug of fascist ritual.

With no less than a hundred thousand participating, it was the largest and most spontaneous political demonstration ever seen in Harlem and marked the highest tide of popular political enthusiasm ever witnessed among American Negroes.

Negro voices called fraternally to Jewish-looking faces in passing autos:

”I bet all the Jews are happy tonight!”

As I’ve stated before here at The Wild Hunt, boxing has inspired a staggering amount of brilliant writing over the past two hundred or so years. Among the titans who have published on boxing and boxers, Wright’s writing stands out as something altogether special.

Even in this relatively brief excerpt, he touches upon sports as something that is part social, part political, and part spiritual. The victory of one athlete over another in a pugilistic contest fought in a squared circle has a multitude of deeply powerful meanings to those who observe, watch, or listen to the fight – and to those who read about it or are told tales of it.

The competitors become something much larger than the individual. Both Angelou and Wright show how their social function expands to mythological levels of intense emotional resonance.

In this context, the fabricated tale of the convict praying to Louis for physical salvation at his moment of execution expresses how much the victories of Joe Louis meant to African-Americans. This internally generated meaning is fundamentally different from the emotional response engendered by myths consciously forwarded by propaganda, as it bursts forth from within rather than being manipulated from without.

For a myth to have meaning, it doesn’t really even matter whether it is factually true or not. This goes for ancient myths as well as modern ones.

The wizard

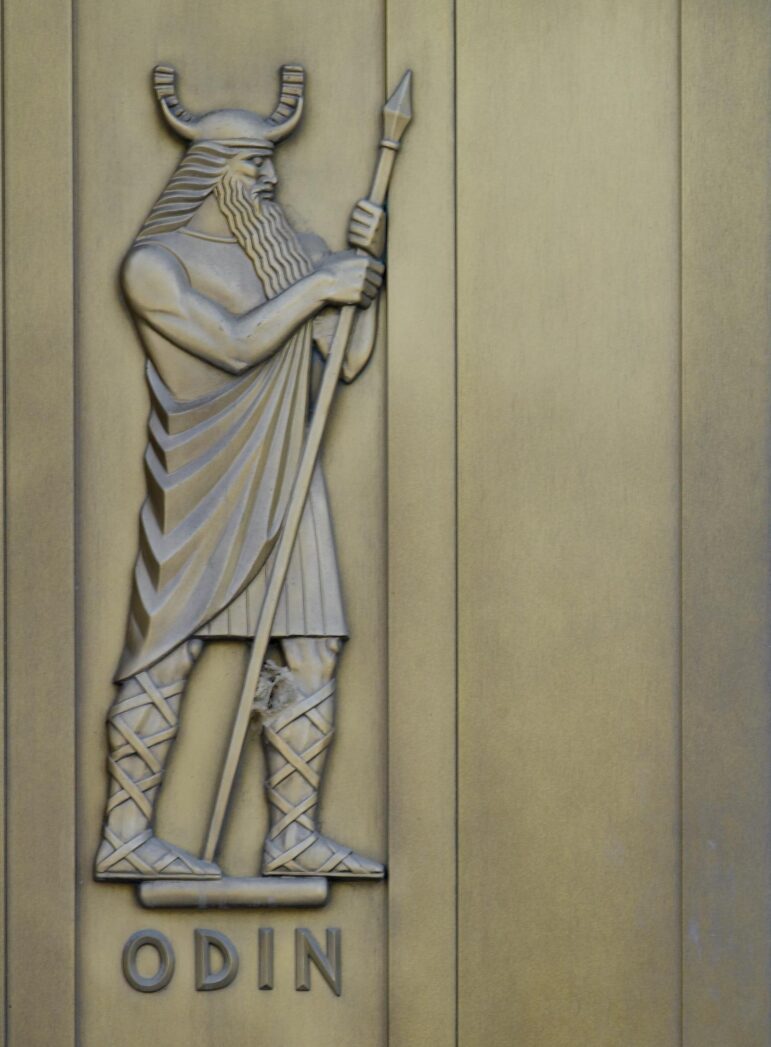

For those willing to listen, the Norse myths have much to say. To appreciate that they are tales of more than surface meaning, to assert that there is more to them than entertaining plot, is not to claim that they are literal records of actual events.

The myths tell us of Odin the Wanderer, the god who takes on the guise of an old man with a spear as a walking stick who advises heroes, challenges other deities, and quizzes ancient giants. We read of Odin as inspirer of creativity, as instigator of conflict, and as dispenser of wisdom.

Bronze figure of Odin by Lee Lawrie on east entrance of Library of Congress John Adams Building [Library of Congress]

If we don’t accept Snorri Sturluson’s classicist euhemerism as inherent to Old Norse religion, and if we take the lessons from history of religions and comparative religions to heart, we can read the mythical Odin as a poetic representation of divine power with a specific set of attributes – as a character of story who enables us to relate to and better understand a spiritual force by giving it human characteristics and setting it into literal dialogue with other such representations.

My single most favorite line from my years in divinity school is from Paul Ricœur, a conservative Christian philosopher with whom I otherwise would have no truck. In The Symbolism of Evil (1960), he writes:

I shall regard myths as a species of symbols, as symbols developed in the form of narrations and articulated in a time and a space that cannot be co-ordinated with the time and space of history and geography according to the critical method.

Following from this, the character of the long-bearded wizard Odin is a symbol for a cluster of forces related to inspiration and possession. Odin, as it were, puts a face on the forces so that we can better grasp what can otherwise be overwhelming – as the warrior Arjuna was overwhelmed when his charioteer Krishna revealed his ultimate, cosmic, and fully divine form to him.

Furthermore, when portraying this divine power in wizardly form, the myths can show us its interaction with other divine powers likewise portrayed as characters of story.

We read of Odin interacting with Thor the Thunderer, the embodiment of the storm, of passion, and of socially sanctioned behavior for the good of the community. We read of the two of them interacting with giants, representations of both ancient inherited wisdom and of destructive natural forces.

The interactions of the god-characters limn as much non-literal truth as do their individual characterizations. The myths ask implied questions and provide possible answers by setting these figures next to and against each other.

By engaging with the myths “as symbols developed in the form of narrations” instead of as literal representations of events “co-ordinated with the time and space of history and geography,” we can get to deeper truths.

But the lure of literalism always lurks.

All too real

The danger of any propaganda, no matter how well-meaning, is that the appeal to emotions over intellect can all too easily slide into celebration of baser instincts. Taking the “good fight” to the Nazis was absolutely necessary, but along with ramping up support for the fight against fascism, the war machine also promoted racist stereotypes and xenophobia.

On a parallel track, the danger of reading any myth as a literal representation of physical reality is that the surface details are elevated and sanctified over the deeper meanings. Gandhi warned of reading ancient myths of battle as always and only about men fighting and killing other men and instead challenged us to read the old tales as representing the internal struggle of the spirit in narrative form.

Should we turn to tales of Odin as instructions for finding an actual wizardly sponsor in the forest who will gift us powerful weapons with which to slay our perceived enemies? Or should we read them as meditations on finding our own paths and coming to terms with our own inevitable deaths?

Should we read tales of Thor as injunctions to heft blunt objects and mortally bludgeon those with whom we have differences? Or should we read them as ruminations on the difficulty of standing up for the good of our wider communities when doing so can bring harm down upon ourselves?

Today, too many tread too easily the path to hatred and violence as they feast upon myths that they tell each other about the Other who lives next door. Maybe they believe a character from Norse myth literally manifested in their bedroom and told them to smash in the heads of those who subscribe to other theologies. Maybe they believe pedophilic snake-people have taken over the political party they oppose and must be stopped by second-amendmenting them to death.

For the violently deluded, the myth has become all too real. The barriers between mythology and reality have broken and breached.

I began this column by asserting that mythification can have profound effects lasting for generations and that myth, regardless of veracity, can have more power than any truth.

I’ll end it by affirming the vibrant value and positive power of myth in our lives, when approached with an open mind and a poetic mindset – and by rejecting the propagandistic approach to myth that reads it literally even as it uses it as an excuse for embalming ourselves in our worst emotions.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.