I read about boxing every day.

Sometimes it’s a few pages in a book on the early days of bare-knuckle boxing or the history of the heavyweight champions. Sometimes it’s a report of a fight that just happened or a preview of one that’s about to happen. Sometimes it’s just browsing tweets on boxing Twitter to see what people are arguing about today.

Always, it’s been The Ring.

Since I first got into boxing twenty years ago, the magazine that calls itself “The Bible of Boxing” has been my go-to for everything related to fights, fighters, and the scenes that surround them.

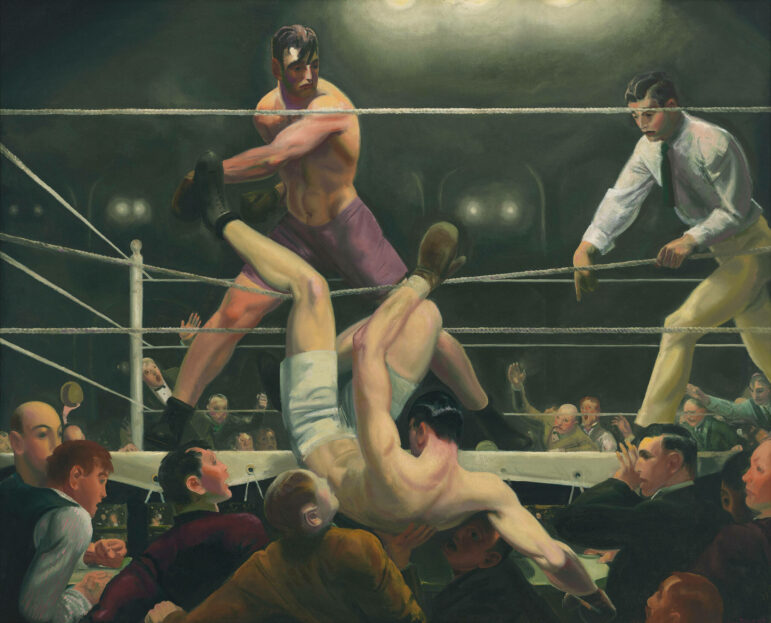

Dempsey and Firpo by George Bellows (1924) [Public Domain]

Those who aren’t steeped in boxing literature might wonder just how much can be written about two guys hitting each other inside a roped-off ring that’s actually square instead of ring-shaped. It turns out that boxing writers, like baseball writers, have and continue to write some of the most amazing prose you’ll ever find.

The fact that the event is so (literally) stripped down, so basic, and so primal while simultaneously being so skilled, so subtle, and so artistic brings out the strongest and deepest writing from authors who feel the attraction of fight night. Some of the most hypnotically good writing I’ve ever read in my nearly half-century as an obsessive reader has been from the boxing bookshelf.

So many authors from so many disciplines have written so excellently on boxing over the last two-hundred-odd years. Some approach it as historians, some as reporters, some as cultural analysts, and some as writers of creative fiction.

Just saying their names to myself gives me a reflected thrill of the excitement and joy that I’ve gotten from their work: Pierce Egan, A.J. Liebling, W.C. Heinz, Nellie Bly, O. Henry, Jack London, Ralph Ellison, Norman Mailer, John Lardner, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Jimmy Cannon, George Plimpton, Robert M. Lipsyte, F.X. Toole, Roger Kahn, Nick Tosches, Nelson Algren, Randy Roberts, Hugh McIlvanney, Damon Runyon, Lewis Erenberg, Joyce Carol Oates, Geoffrey C. Ward, Rod Serling, Red Smith, William Campbell Gault, Herb Boyd, Budd Schulberg, Paul Gallico, James Baldwin.

That’s quite a list, and there are a great many more to add.

There’s also a tradition of wild (and often wildly fanciful) autobiographies written by, co-written by, or ghostwritten for the boxers themselves, like the books credited to Joe Louis, Max Schmeling, Jake LaMotta, Rocky Graziano, and Muhammad Ali. All are fantastic reads, even if they’re sometimes closer to fantasy than to history.

No matter what book I was reading, the latest issue of The Ring was always on my nightstand. It was the constant line that connected the past, present, and future of boxing.

And it just died.

Counted out

In the early years of the twenty-first century, before the first iPhone was born, I would regularly stop by the local newsstand to pick up the latest issues of The Ring (USA) and Boxing Monthly (UK). I had a deep sense of loyalty to our domestic magazine, even if I secretly liked the wit of the writers and the cleverness of the boxers a bit better in the British production.

One of the major thrills of my life was when both publications ran coverage of my 2010 album Portrait of Jack Johnson, which featured my Boxing Bassist Suite, a set of jazz compositions inspired by African-American boxing champs who were also (like me) string bass players – Johnson, Archie Moore, and Ezzard Charles. What can I compare the feeling to? It was just too cool to be in those pages, sandwiched between actual fight news.

Contemporary coverage of Jack Johnson vs. Jim Jeffries (1910) [Public Domain]

But now the concept of newsstands seems like something from a long-past time, and both of the magazines have folded.

Boxing Monthly was the first to go, ending a run that began in 1989 with its May 2020 issue. That was a hard hit, but surely The Ring would go on forever!

Over the past few years, I’d gotten years behind on my boxing magazines. Through a combination of work, family, health, general life issues, and my determined insistence on reading every word on every page of every issue, the row of magazines under my nightstand kept getting longer and longer. I’ve been making a focused effort for a while now to get caught up. I’m now in April 2022 and watching some of last year’s big fights on YouTube as I read about them.

The February 2022 issue of The Ring was a supersized “Collectors’ Issue” celebrating the magazine’s 100 year anniversary. By the end of the year, the chronicle of the boxing world had outlived major mainstream print magazines like Life, Newsweek, McCall’s, Martha Stewart Living, Cracked, and Playboy. This definitely meant The Ring would go on forever!

A few weeks ago, I noticed that my shelf of magazines yet to read wasn’t as wide as it should have been. Turns out the last issue I had was Nov/Dec 2022, a weird two-month designation for a monthly magazine. Maybe my long-term subscription had finally run out.

When I turned to Google, I was blindsided by the months-old news that The Ring had shut down its print magazine at the end of 2022. Impossible, but true. Being so far behind in my Ring reading, I’d completely missed the fact that the magazine was dead as a magazine and had decided to continue on as a website, as so many other of the old newsstand standbys have attempted to do over the years.

And it hit home yet again that I’m a person who loves lost causes.

It’s over before you begin

I don’t mean “lost cause” in the horse-manure sense of racist historical revisionism that pretends the Confederates were noble fighters for freedom and that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery.

I also don’t mean “lost cause” in the sense of deluded and retrograde insistence on enforcing tired, old, oppressive concepts of gender, sexuality, race, religion, and the rest of the things that our de-evolved fellow citizens are so determined to push back to the ways of the bad old days and force upon those of us living modern lives in the modern world.

I mean the romantic and Romantic sense of connection to things that had their time and passed, that once strode boldly across the stage of everyday people’s lives but are now relegated to specialty shops and niche fandoms.

I’ve long been fascinated by the fact that someone (musician, athlete, actor, author) can be a superstar and household name for a decade, then be completely and totally forgotten a decade later. I always assumed that high levels of extreme fame would fade bit by bit over the years, slowly sliding down a very gradual slope into faded obscurity. Instead, bright stars in our collective cultural consciousness tend to burn bright and burn out fast.

I’m not sure why I so deeply love things with big histories that are trapped there in history. Maybe it has to do with a subconscious longing for eternal youth.

Rock ‘n’ roll is one of those lost causes I love so much. Ray Davies of the Kinks perfectly portrayed the feeling I’m talking about in his lyrics for the band’s 1972 track “Celluloid Heroes,” a song that always overwhelms me with feelings of longing and loss.

You can see all the stars as you walk down Hollywood Boulevard

Some that you recognize, some that you’ve hardly even heard of

People who worked and suffered and struggled for fame

Some who succeeded and some who suffered in vainI wish my life was non-stop Hollywood movie show

A fantasy world of celluloid villains and heroes

Because celluloid heroes never feel any pain

And celluloid heroes never really die

Marilyn will always be young, beautiful, hilarious, and tragic. Lemmy will always be raging with the power of rock. Muhammad Ali will always be standing over Sonny Liston, yelling at him to get up off the canvas. For these legends, time has ceased to function.

Not so for the rest of us. I sometimes wish I’d never head Pink Floyd’s 1973 album Dark Side of the Moon, because Roger Waters’ lyrics to “Time” have been haunting my thoughts in the past few years leading up to my fiftieth birthday.

Tired of lying in the sunshine, staying home to watch the rain

You are young and life is long, and there is time to kill today

And then one day you find ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gunAnd you run, and you run to catch up with the sun, but it’s sinking

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way but you’re older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

Another song that I uncomplicatedly loved as a thirteen-year-old kid but now both love and dread as a middle-aged man is The Who’s 1971 track “When I Was a Boy,” written and sung by bassist John Entwistle.

When I was a boy I had the mind of a boy,

But now I’m a man, ain’t got no mind at all

When I was in my teens I had my share of dreams,

But now I’m a man, ain’t got no dreams at allMy how time rushes by,

The moment you’re born you start to die,

Time waits for no man,

And your life’s spent, it’s over before you begin

Now I’m starting to wonder if my decades-long obsession with early-1970s British rock is actually the root cause of my likewise lengthy flirtation with depression.

It’s not just musty vinyl records of past rock styles that appeal to me. I obsess over pulp paperbacks from the American kung fu craze of the 1970s and practice kung fu styles developed in China centuries ago. I perform music written by 19th-century composers on that most unwieldly of all portable orchestral instruments (with the possible exception of the harp), the string bass. I make music by rubbing strings of gut and copper with hairs cut from the tail of a horse. What year is this?

Like boxing, none of these things will ever again have the massive mainstream popularity they enjoyed in the past. So many of my truest loves are of this nature – things that are past their glory days but can still be deeply exciting and profoundly moving, at least to those who can still hear their siren songs.

It’s profoundly sad to me that magazines and books are going the way of the 8-track cassette. I spent so many hours of my childhood wandering between the back shelves of used book stores, searching for something exciting and affordable. I spent many more hours inside, outside, on the couch, and under blanket forts, always reading. The annual used book sale that used to happen in giant tents in a local shopping center parking lot was part of our family calendar. The smell of old pages is still delicious to me.

The used book stores I haunted are all long gone. The annual book sale in the tents stopped happening nearly twenty years ago. Like The Ring, they’re now just memories of a bygone era, a lost cause that had its moment.

Of course, the biggest of my lost causes is Norse religion.

Odin and the Old Way

When I first came to Ásatrú and Heathenry, modern iterations of Old Germanic paganism, I had the typically giddy newbie naïveté that led me to think that, yes, we can bring this back and have temples in major cities and get included in mainstream theological discourse and get invited to participate in interfaith leadership and we can really make a serious impact for positive change in the world.

That was all before facing the condescending and snotty snobbery of corporate media religion reporters, the un-self-aware rudeness of faith leaders in majority religions, the probably illegal statements of open prejudice by college and university administrators, and the realization of just how incredibly deep the racist rot has spread throughout the myriad forms of this thing of ours.

I no longer have any urge to raise a temple in the big city, to sit on a panel discussion on world religions, or to help lead an interfaith organization. The Heathen groups are too compromised, too ready now (as they were decades ago) to “look past personal political differences” and turn blind eyes to the deeply problematic connections and convictions of their members. Largely because of this compromised nature – and I say this because I’ve been explicitly told this by multiple faith leaders – we will never be truly included in the wider theological and interfaith world.

Nowadays, the cause that I care about is to practice Ásatrú with friends, family, and family friends in Thor’s Oak Kindred. Having a relatively small, local, and face-to-face group that has no ties whatsoever to other groups (local, regional, national, or international) is probably closer to the way the Old Way was practiced in the old days, anyway.

I have no illusion that we’re reconstructing some religion of the Vikings or ancient Germanic tribes. Instead, I accept that we’re practitioners of a new religious movement (as academics call it) that looks to the old religions for inspiration and illumination. We model what we do on the best of what they did, and we forget the stuff that doesn’t make sense with our lives today. Honoring lost loved ones while speaking over the horn, yes. Bloody sacrifices to insatiable gods of war, no.

Yes, I read accounts of the Old Way in its day with love and longing. I am profoundly moved when I read the sayings of Odin, whether by myself, in communion with the kindred, or discussing them with college students. I see the lore as touchstones for righteous living, guidelines for right action, and comfort in the darkness. We can deeply care about all of this without pretending that we can go back and do like they did.

Maybe one of the reasons that I so strongly embraced this path is that the sense of the lost cause is right there in the poems, myths, and sagas that we love so much.

Odin spends much of the mythological present wandering the world to gather wisdom from ancient giants, mystically pickled heads, and visionary seeresses living and dead. His goal is usually to find out more about Ragnarök, the doom of the gods.

Odin (Wotan) as the Wanderer by Arthur Rackham (1911) [Public Domain]

Everything he learns confirms that the cataclysmic final battle is coming and is unstoppable. It’s a lost cause.

But the wandering god doesn’t simply accept the inevitable and give in to despair and hopelessness. He does everything he can to minimize the damage, to ensure that life continues past the end of this cosmic time cycle and into the next.

To embrace the lost cause is to declare that something is worth saving, even if all signs point to its ending.

The main event: Thor vs. Jesus

When Christianity came to the far north, Thor became a symbol of the Old Way’s defiance of the major religiocultural shift that was happening. Thor’s hammer pendants already had a long history, but they surged in popularity among pagans in reaction to newly converted Christians wearing small crosses as a sign of their allegiance to the new faith.

The image of Thor having a big red beard comes from Christian writers after the conversion had become settled societal reality. It appears in the context of religious conflict, when Thor challenges converters and converted, demanding that they turn back to the faith of their forefathers and reject the new creed. The thunderer with the red beard becomes the symbolic embodiment of the lost cause.

Illustration of Thor (Donner) by Arthur Rackham (1910) [Public Domain]

One of my favorite moments in Icelandic literature occurs in Njál’s Saga, composed around 1280 but taking place between 960 and 1016. When the belligerent Saxon Christian priest Thangbrand travels to Iceland to enforce conversion, he is confronted by a woman heathen poet named Steinvora.

She preaches the traditional religion to the missionary in a long speech and taunts him by insisting that it was Thor himself who crashed the priest’s ship. “Little good was Christ,” she says, “when Thor shattered ships to pieces.”

The greatest moment comes when she asks, “Have you heard how Thor challenged Christ to single combat, and how he didn’t dare to fight with Thor?”

I’ve long had a mental image of Thor waiting on the black sand beaches of Iceland for Jesus to show up, pacing up and down and looking at his watch as the day draws on, finally giving up at sunset, realizing that the Son of Man is a no-show, and heading back to Asgard.

Did Thor, winning the bout by default, realize that the greater tournament would be lost?

I think a lot about the idea that the divine representatives of these two great faiths were scheduled to fight, and the one who didn’t show up is the one who was eventually handed the championship belt. To anyone who follows boxing and its frankly awful sanctioning organizations, it’s well-known that titles and belts can be awarded to and stripped from boxers for many reasons besides who is and who isn’t the best fighter.

As a devotee of Thor, I realize that I’ve chosen to back the historical underdog, the one who still fights for the lost cause of the Old Way in this modern world.

It’s not a fight to convert others or dominate others. It’s a fight to keep our modern vision of an ancient practice alive like a thunder-hammer beating in our hearts, even when all signs suggest that we will always remain small communities at the edges of the international interfaith milieu.

When you truly love a cause, it doesn’t matter if it’s a lost one.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.