“All worlds are moved by lovers.”

Orpheus says this in the underworld, which is not quite an afterlife but more a bureaucratic holding space where men have meetings among cold ruins. He is trying to convince his lover, who is Death herself, that they can prevail over the forces keeping them apart. These forces include his own wife, Eurydice, Death’s orders and obligations, and the mysterious portals between being and un-being that each character accesses through mirrors in their own bedrooms.

Through this mirror comes Death, a wasp-waisted María Casares. It is she who compels the plot, first by appearing to Orpheus (a virile and young Jean Marais) after a brawl at the Café des Poets. Cégeste, another young poet, is hurt in the brawl, and Death (in the guise of a princess) transports the young man in her car. Jean Cocteau is a filmmaker obsessed with the bizarre and implacable logic of dreams; the viewer can guess right off that Cégeste is not on his way to any hospital. Instead, the adventure to the realms of the underworld begin here.

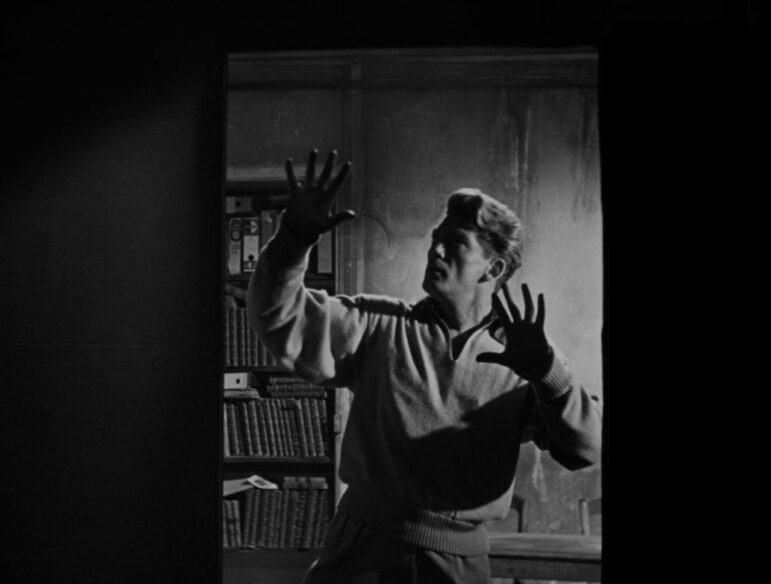

Jean Marais as the title character in Cocteau’s “Orpheus,” 1950 [Film Grab]

Heurtebise, an acolyte of Death, explains the nature of travel through the mirror to Orpheus to allow him into the underworld. He brings the poet to the portal and tells him: “If you look into a mirror all your life, you’ll see Death at work, like bees in a hive of glass.” Thus, Orpheus is shown one of the many worlds not moved by lovers. The body is changed by the lover, certainly, but its decay is not slowed. All worlds have their own rules. Orpheus cannot wake his pregnant wife from death, and Death cannot take the living poet for her own simply because she wants him.

There’s sort of a plot in the waking world: Orpheus receives cryptic broadcasts from his car radio. These come in the form of aphorisms and epigraphs not unlike the ones broadcast by the French resistance during the Nazi occupation. These turn into his poems, which are remarked upon as possible plagiarism, perhaps stolen from the dead Cégeste. All this becomes irrelevant before the life-and-death drama of most of the film, all of it an excuse for Cocteau to tell a very old pagan story in a new way.

In an interview, Cocteau expressed frustration that viewers might try and project a Christian cosmology onto this film. “Among the misconceptions which have been written about Orphée, I still see Heurtebise described as an angel and the Princess as Death. In the film, there is no Death and no angel. There can be none. Heurtebise is a young Death serving in one of the numerous sub-orders of Death, and the Princess is no more Death than an air hostess is an angel. I never touch on dogmas. The region that I depict is a border on life, a no man’s land where one hovers between life and death.

Casares’ Princess Death is costumed primarily in black by midcentury fashion giant Elsa Schiaparelli, but in a few striking scenes, one camera angle shows her in the exact same costume in white. This puts the viewer in mind of image shown in negative, or even of the black and white pillars of the High Priestess card of the tarot. She is the two pillars, she is her own negative, she is Death both as tragedy and as bringer of relief. Older than Eurydice and more worldly in her fashions, her knowing look, her forceful personality, Death provides a counterpoint to the lively loveliness of Orpheus’ young wife. When Heurtebise (whose name is the old French appellation for folks buffeted by the cold and unlucky north wind) asks which woman the poet will seek in the underworld, Orpheus’ loyalty is split. He says he must find both.

Maria Casarès as Princess Death in Cocteau’s “Orpheus,” 1950 [Film Grab]

Death takes Eurydice (a fresh-faced and underutilized Marie Déa) in her sleep and the poet must confront the twisted results of his infidelity. Traversing the realms of the dead, Orpheus finds a ruined landscape of perpetual twilight. One sees the crumbling arches and tumbled stones and cannot help but imagine Cocteau, living in a country still recovering from WWII, perhaps looking upon the ruins of Paris. This world between worlds, says Heurtebise, our Virgil, is made up of men’s memories and habits. Death’s handmaids—two unspeaking corseted motorcyclist twins, carry limp bodies, hold the doors open, stand as bodyguards to her. Cocteau runs the film forward and backwards, showing characters donning gloves in eerie reverse, using this primitive type of special effects to move solid actors through solid mirrors and make us believe it.

Orpheus pursues Death through classic dream scenarios: his fans ask for his autograph only for him to discover he has no pen. He asks Death questions about the nature of the universe: where do her orders come from? A Greek character asks a Greek god about the gods, and she gives a French answer. Her orders are as drums, beating out the news from tribe to tribe. Her orders come down from the mountains and sound like the wind whispering through the trees. She muses that perhaps we are only the dreams of a god, and a bad dream at that. The scene shifts without warning so that Orpheus and Death lie not on the broken stones of a postwar underworld, but on a soft white bed where lovers may pledge their forevers. The poet wrings a forever from Death, the only lover he will ever have who can really promise him that.

Death, who has never waited like a mortal lover, remarks that it must be agony for men to wait all the time as she bids her lover a temporary farewell back into his fleeting life. She is changed by having had him, and changed again to know she must wait to have him for good.

Awakening alive from what seemed like strange dreams, Cocteau’s Orpheus and Eurydice find themselves on the other side of the myth. In the original Greek, Orpheus looks back at his lover and loses her to Hades permanently. Bereft, he plays his lute and sings to death until he is set upon by maenads and torn apart. This tragic 1500 year-old love story has inspired paintings, sculptures, plays and operas, spawning new works of art until Cocteau’s surrealist film in 1950 and the musical Hadestown in 2006. Most of them are faithful to the fate of the lovers, seeing all of love’s labors lost.

It would be easy for the viewer to take in Cocteau’s final scene of morning sunshine and blonde lovers finding one another whole and alive, speaking of their child yet to be born, and assume the director made a fundamental change to the shape of the tale, forcing a happy ending into this centuries-old one of woe.

It is Death’s final words that make this impossible to mistake. Orpheus and Eurydice haven’t dodged their fate. They’ve only postponed it, which is all any lovers can hope for.

All worlds are moved by lovers. Just not for long.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.