“I think we have a problem,” I said to my wife.

She looked up from the baby, who she held in her lap along with a bottle of milk. In our attempts to regain some kind of sleep schedule, we have started the classic routine for a new child: bath, bottle, book, and bed. The baby had already had a bath and was now working on the bottle. I had read a few of the books on the shelf already, and the baby was starting to doze off – soon for the last B of the quartet, we hoped, though at the moment a glint of light still reflected off of the child’s just barely open eyes.

“What’s that?” she asked.

I held up two identical wooden blocks, each stamped with an image of a man bent low under the weight of a massive boulder.

“We’ve got two Sisyphuses and no Graces.”

The Aphrodite block from Uncle Goose’s Greek Mythology block set [E. Scott]

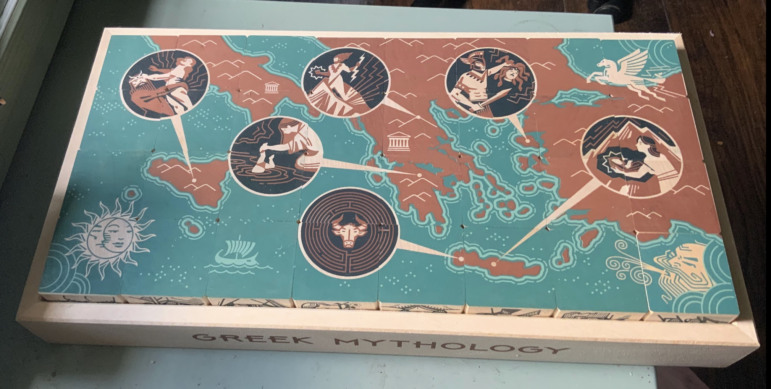

It was from a set of blocks given to us by the mother of my best friend, each of which featured a figure from Greek mythology. The blocks are made by a company in Michigan called Uncle Goose, and each one has an illustration of the character on one face, then faces for the character’s names in English, Roman, and Greek, a face for an epithet – Sisyphus’s is “Iron Fisted King” – and, finally, a face that combines with the rest of the set like a jigsaw puzzle to form a map of the mythic Aegean Sea.

I loved the blocks as soon as we opened the box – it was a very “us” present and a welcome change from the parade of plastic noisemakers that are an unavoidable part of having a small child. Mostly what I love about them, beyond how pretty they are sitting in their basswood tray – I know that before long they will be scattered around the floor of the baby’s room, never to be reassembled – is the future they represent. I picture my child picking up one of the blocks and asking me to tell a story – the myth of Theseus and the minotaur, or the names of all the Muses.

That is to say, I am picturing introducing the baby to myth, and from myth, to a life with the gods.

The blocks of the Uncle Goose Greek Mythology set combine to form a map of the mythic Aegean Sea [E. Scott]

I know that many Pagans can point to a particular book of myths as their introduction to what would eventually become their religion – many point to the D’Aulaires’ books of Greek or Norse myths, for example. Strangely, given that my childhood was not only Pagan but extremely bookish, I can’t recall a particular version of the myths that formed the basis of my relationship with them. I still have A Treasury of Greek Mythology by Alison Witting on my shelf, a book I know I’ve had since I was a child, but I can’t honestly remember ever sitting down to read it.

Looking over my shelves now, I count a dozen or so collections of myths from the Greeks, the Norse, the Egyptians, and the Celts, but in all cases, I recall coming to the books long after I had originally learned the myths within them; my memories are not of discovering new stories, but of finding that the story had been told in different ways by different people, or that some detail I thought I knew was actually an embellishment not found in the original.

(Though I would be remiss at this point not to mention one other major source of my childhood mythological knowledge – namely, Marvel Comics, with their bright Kirby-crackle image of the Norse mythos. I didn’t read anything like the actual myths from the Eddas until I was a teenager. To this day, the first image of Yggdrasil that comes to my mind is the diagram of the Nine Worlds under the entry for “Asgard” in The Official Handbook to the Marvel Universe, Vol. 1: Abomination to the Circus of Crime.)

If the myths did not come to me from books, they came to me from my parents, who must have told me the stories when I was too young to remember being told them. To put it another way, I had myth before I had memory. And long before I knew my wife and I were going to have a child, I daydreamed of telling the stories of heroes and gods to the baby. Indeed, it was the only thing about fatherhood I thought for sure I could handle.

Thor, Loki, Thialfi and Roskva following the giant Skrymir by George Wright, from Mabie, Hamilton Wright, “Norse Stories Retold from the Eddas,” 1908 [public domain]

The baby was born 11 weeks premature, which is to say, the baby spent the first three months of life in the hospital’s NICU, unable to come home with us. The baby spent much of that time hooked up to various kinds of devices: an incubator, because the baby was too small to keep warm; a bubble CPAP machine, because without it sometimes the baby would stop breathing; a feeding tube, because at first the baby was unable to drink from a bottle.

For weeks we could go to the hospital after work and see our baby, hold our baby, and feed our baby, but then at the end of the night, we would have to put the baby back in the crib and make the lonely drive back across the Mississippi River alone, even if the baby started crying when it became apparent that mom and dad were leaving yet again.

Late on one of those nights, after the lights were turned out and the baby had eaten, I reached for my much-loved and battered copy of The Norse Myths by Kevin Crossley-Holland and flipped to my favorite of all myths, the story of Thor and Loki visiting Utgard. I had spent years imagining telling this story to a child, more than any other. I had practiced the voices: the gruff and chummy thunder god and his sly, cat-like accomplice, the booming voices of the giants turning slowly to fear and apprehension as they realize that despite all their trickery Thor is more than a match for their challenges. I imagined my child squealing with delight, shouting out all the answers to the giants’ riddles before I could say them, demanding that I tell the story again just as I got to its end.

The baby was, I think, still in the incubator at that point, still wearing the CPAP mask whose hated prongs led to tantrums every time the nurses changed them out. I put my finger on the first line of the story and paused. The baby was asleep, and even awake, had no sense of language, much less of story, less still of gods and giants. Was there any point to this? Would it have the same impact if I just babbled softly against the plastic wall of the incubator, or read out the news?

The conclusion I came to was this: myth has been for me a bedrock of narrative, a foundation on which I have built everything else about my life. Myths are stories that were part of me before I knew there was a “me” for them to be a part of. I have never not known them. And they are, in the end, the things that made me the person I am.

The baby would not remember this telling of the story, it’s true. But perhaps instead the baby would always remember having been a part of this story, sliding into the chariot next to Thialfi and Roskva, quivering before the might of the giants, but always knowing that the Thunderer would be there to protect all children from harm. Perhaps myth will be as much a part of my child’s life as it has been a part of mine.

“This is my favorite story, buddy,” I say to the baby, who kicks the mattress as if in response. “I hope you’ll like it too.”

I look down at the page of this book, one of the many collections of myth already waiting for us at home, and start to tell the tale.

Author’s note: Uncle Goose immediately sent us a replacement block for the Three Graces, so now the baby has some grace. Dad will take care of that extra Sisyphus.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.