Editorial Note: The article discusses experiences of violence and abuse

Spring is here, which means it’s time for baseball books.

Due to the overlong and needlessly contentious lockout of players by owners, this year’s first spring training games were pushed back far enough to nearly coincide with the spring equinox. So, as we celebrate winter’s end by hailing the Vanir in Thor’s Oak Kindred, I also reach for my first baseball book of the season.

This year, that first book was Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original, Mitchell Nathanson’s 2020 biography of pitcher, writer, and activist Jim Bouton. This first biography of one of my favorite baseball players was perhaps a bit too careful, a bit too much from the perspective of a fan.

I was a bit disappointed that Nathanson didn’t really dig deeply into the questions I’ve had after reading every book Bouton wrote. One area that was lightly skipped over was an analysis of the writing that those in the Bouton circle themselves published in the wake of Ball Four’s success. This bit, in particular, struck me as odd:

In 1975, Joe Pepitone published his tell-all, hoping to even the score with Bouton by dishing on the Bulldog’s sexual habits. It caused a sensation. Then it disappeared.

This seemed odd. Could first baseman and center fielder Pepitone, one of the most colorful colleagues portrayed in Bouton’s book, really have written an entire book about Bouton’s sex life just to get even? I headed to eBay.

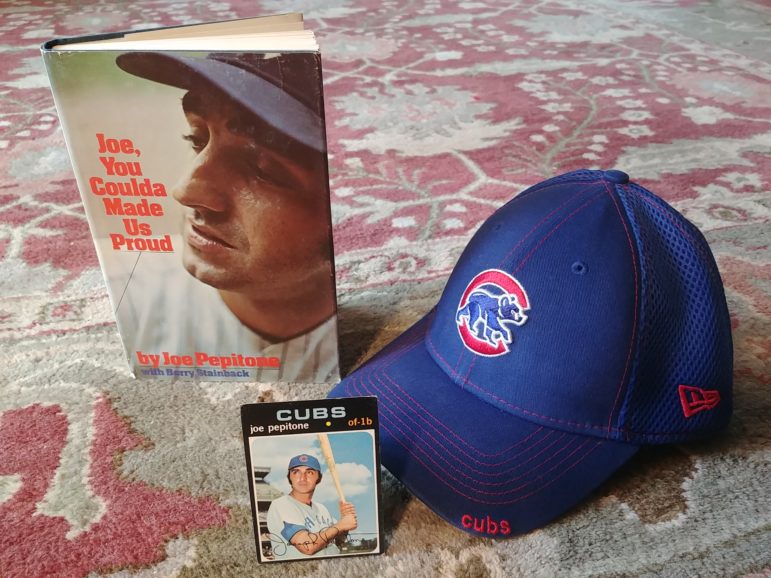

1975 first edition of Joe, You Coulda Made Us Proud, 1971 Topps baseball card of Pepitone with the Chicago Cubs, and modern Cubs cap [Photo by K. Seigfried]

The only bit about Bouton’s dalliances in the entire book is one paragraph in the penultimate chapter, in a section of short anecdotes that seem to have not quite fit the flow of the book’s narrative and were included as outtakes at the back. In that single paragraph, Pepitone and another player hit on a girl Bouton is talking to in a bar and end up leaving the pitcher standing alone as they walk out with her. That’s it. Not quite the “dishing on the Bulldog’s sexual habits” that Nathanson claims.

What is Pepitone’s book really about, then? It’s a soul-baring autobiography that, at its core, is about extremely violent child abuse and the long shadow that abuse can cast over a life. The book’s title reflects the self-destructive adulthood that followed the battered childhood: Joe, You Coulda Made Us Proud.

Pepitone’s detailing of abuse and its consequences can be meaningful for Pagan readers and, especially, Pagan clergy.

“Joe Pepitone’s old man is gonna ruin that kid.”

Published in 1975, just two years after his final game in Major League Baseball, the autobiography by the then-34-year-old spends its first five chapters detailing the grim reality of Joe’s abuse at the hands of his father, William Pepitone – known as “Willie Pep,” after the Italian-American midcentury boxing champion. The Pepitone patriarch was quick with his fists and is introduced by Joe as “bigger and a helluva lot tougher” than the boxer and “the toughest guy” in “a very tough neighborhood.”

“He had a furious temper,” writes Joe, “and, when he wasn’t spoiling the shit out of me, he was beating the shit out of me.” That dichotomy, instantly recognizable to victims of abuse, plays out throughout the first section of the book. Young Joe both worships his father and is terrified by him.

To be clear, this is violent child abuse in extreme form. Joe writes, “He never pulled his punches, left me black-and-blue and bloody, particularly as I got older.” If Joe is even five minutes late for curfew, “Willie would punch the shit out of me.” If Joe’s younger brother gets into a fight, Willie explodes at Joe for somehow failing to protect his sibling and would “beat the hell out of me with his fists, bloody my nose, leave bruises all over my face.” When fifteen-year-old Joe is involved in a gang-fight at a roller-skating rink, his father punches him full force in the back of his head and smashes his head through a washing machine window.

But, like the violent frenzies of Viking-age berserkers, Willie’s rages are followed by exhaustion. Joe writes,

Usually, right after he’d beaten me, my father would cool down and apologize to me, saying he was sorry, that he didn’t mean to hit me so hard. Almost every time he’d beat me, he’d come back minutes later and apologize. Finally I told him, “Dad, don’t apologize to me–just stop beating me, or at least make sure I deserve it.” But he couldn’t control that temper. It would just explode!

There is that recognizable split in the violent abuser, and there is the also sadly recognizable split in the victim – the deep desire for the abuse to stop coupled with the sense forced upon their psyche that they somehow “deserve it.” Indeed, Joe tries to rationalize his own childhood abuse:

He wanted only good for me, wanted me to do right, wanted to teach me about obligations, responsibilities. It took me years to understand, to realize that the beatings were a reflex, his way of teaching me, the only way he knew. The constant beatings followed by apologies were not the best way, not for me. Willie didn’t know that. I think he loved me too much, wanted too much for me, expected too much from me.

Joe continues, “I know I loved him too much” and reflects,

I wonder if ever a father has been such a god to his son? I know now, though, why being alternately praised and put down by a god was so painfully confusing, disorienting. Bless you, Willie; damn you. I miss you.

The final blow comes after Joe becomes a breakout local baseball star for the Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs semipro team. His father is such a problem at games – fighting in the stands, fighting on the field, wrecking Joe’s concentration, and bringing his playing down – that professional baseball scouts start to lose interest in Joe and say, “Joe Pepitone’s old man is gonna ruin that kid.” When Joe’s agent-advisor finally calls Willie and tells him to stop coming to games, Joe’s father predictably explodes and tells him that Joe will never play baseball again.

After Joe responds to what seems the needless killing of his baseball career by telling his father “I hate you!”, Willie throws a thick glass ashtray at him. Joe twists out of the way, but the ashtray shatters the china closet, and shards of glass slice into Joe’s face. He can’t open his eyes as blood pours down his face.

In one of the most painful episodes of the book, Joe describes Willie’s reaction to his own horrifying violence.

My father let out a cry like a dog that had been run over. I felt him hug me, lift me up, sobbing, his body shaking, and felt him carry me down the stairs to the street. He gently eased me into the car, then raced to the hospital, his hand clamped on the horn, never stopping once.

In the emergency room, the doctors force open Joe’s bloody eyes and pick out the shards of glass. Amazingly, there is no permanent damage, but there is a lasting result:

My father never hit me again, though, after this incident. I think the glass in my eyes scared him so much that he finally forced himself to stop punching me.

Instead, Willie vents his rage at his son’s perceived failings by smashing his fists through walls and windows. He also turns from beating to screaming the worst insults he can imagine at young Joe – to the point where Joe begs, “I’d rather you hit me, get it over with!” After the physical damage of years of beatings, Joe is torn down psychologically by his father and made “to feel incompetent even though I knew damn well I wasn’t. It wobbled my head, affected my play.”

At the beginning of Joe’s final season of high-school baseball, both he and Willie end up in the hospital. The father has a serious heart attack, and the son is shot through the middle by another student as part of surging teen violence in 1958. When both are recovering at home, Willie argues with Joe and screams at his mother. What follows is one of those moments that reverberate through the entirety of a person’s life.

I got angry, absolutely furious, and I said, “Mom–I wish he’d die. I really wish he’d die!”

The next night, Joe is woken up by the sound of his father’s grating death-rattle in the next room.

“I kept turning the screw deeper and deeper”

Understandably, Joe has an intense reaction.

Then I went crazy, completely lost control of myself in my guilt over what I’d said the day before. I wanted to hurt myself, to pay myself back for those words about my father.

A deep depression follows. The seventeen-year-old can’t sleep, even with the help of “the most powerful sleeping pills.” It gets so bad that his heart begins skipping beats and he stops going to school, developing blurred vision and losing fifteen pounds. His mother finally recruits his friends to drag him back into daily life, and he’s soon in the middle of a three-way bidding war that leads to a contract with the New York Yankees.

The loss of self-control, the guilt, and the depression continue to swirl around Joe as he moves through the drag of the minor league system and up into the glaring spotlight of major league ball with Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, and a young pitcher named Jim Bouton. As soon as he begins his professional career, he embarks on an epic quest of self-destructive behavior.

He spends more than the money he earns and gets deeply and dangerously into debt, living far beyond the means of even the New York Yankee, All-Star, Gold Glove awardee, and World Series winner that he quickly becomes. The pranks he pulls for laughs cross into criminal territory, as Joe and another player decide to “pull a fake holdup” of an auto parts store they frequent, complete with masks and realistic-looking fake guns, “just for laughs.” Passerby, owners, police, and Yankee management don’t think it’s funny.

In New York and on the road, Joe lives the life of a sex addict. In pornographic detail, he describes endless one-night stands (often several per night) with any and every available woman. Underage, elderly, groupie, prostitute, half-paralyzed (!) – Joe hops into bed with them all, during and despite his marriages and fathering of children. Looking back, Joe reflects that

it wasn’t fun, it was wacky. I think I was simply trying to escape through sex the pain that was crouching deep inside my head; the guilt that went back to my father’s death. Each conquest pushed aside for another night the memories I couldn’t bear to think about. Of course, all the time I was accumulating more guilt over the treatment of my family, and while it was small, insignificant, in relation to those feelings about Willie, my self-destructive performance took its toll.

His first wife rightfully tells him she wants a divorce. Adding another weight to Joe’s load of guilt and depression, his little daughter runs up to him as he’s about to drive off with his clothes.

“Daddy, don’t leave,” she said, hugging my leg. “Daddy, don’t leave me. I’ll never see you any more.” She was crying.

He does leave, and – after a failed attempt at child abduction – his daughter is out of his life, and he has another image of pain and loss seared into his brain that he attempts to push away with night after night of debauchery. Her words play in his head on repeat during baseball games and in the middle of sexual acts.

As a young Italian-American baseball superstar, he is embraced by New York’s “racket guys,” the mobsters who frequent the all-night clubs Joe loves to hang out and be seen at. He embraces them in return, welcoming their protection and the women they supply him with. Despite the haze of endless booze and constant sex, he does have the good sense to turn down their very serious offer to break the legs of the main Yankees first baseman, so “a Italian” like Joe can have the position to himself.

He also discovers that even stardom can’t protect him from the debts he’s racking up at mob-associated venues, as goons show up at Yankee Stadium to inform him that there will be violent consequences if he doesn’t settle his debts. By this point, however, Joe is so committed to drowning the guilt and depression he carries from his father with any sort of rush at all that he finds “the whole thing exciting, another game. It was a kick being able to talk your way out of anything.”

Joe’s life becomes “one long agonized scream” that he tries to cover up “with endless partying.” His pranks and outrageous behavior with women begin to more seriously alienate his teammates, managers, friends, and family. Process servers appear at games around the country to hand him court summonses from the multiple parties to whom he’s delinquently in debt. The constant drinking, the all-night pursuit of sex, and the lack of sleep seriously affect his playing on the baseball field.

Inescapable self-destructive urges lead Joe to first reach out to childhood friends from the old neighborhood, then to a hospital stay with psychiatric care. Instead of opening up to the doctors about his relationships with his father and as a father, he rants about problems in professional baseball. As he leaves, he reflects, “Who wanted to be around a man who was living in agony? Who, I wondered subconsciously, could possibly love such a man?” At least for a while, the answer is another wife.

Then another daughter arrives, then more cheating coupled with insane jealousy. Joe fires the psychiatrist he has been talking to for two years and digs deeper into his personal hole. His second marriage falls apart after his wife finds a suitcase literally filled with bits of paper, each one inscribed with a different woman’s phone number. Joe describes this, yet another low point:

I was running so hard, even my conscience couldn’t keep up to me. Here I was still running, but on my own, with no one to fuck over except myself.

By 1968, Joe is twenty-seven and has “simply lost all interest in baseball.” He’s welcomed on the clubbing scene with jeers and challenges from former fans, and he gets arrested in Detroit for nearly smashing in the head of one of these after-hours hecklers – fully adopting the furious violence of his own father. His behavior becomes increasingly erratic, and, in late 1969, he reads in The New York Times that the Yankees have traded him to the Astros.

Joe quickly chafes at the regimentation of the Astros, walks off the team, and demands to be traded to the Mets or Cubs. The Chicago team takes him, and things are great. Baseball is fun again, he gets married a third time, and he opens his own lounge. But a bad streak with a .125 batting average leads to Joe getting benched at exactly the time he’s back in court for delinquent alimony payments to his second wife. He tells the Cubs vice-president he wants out of baseball.

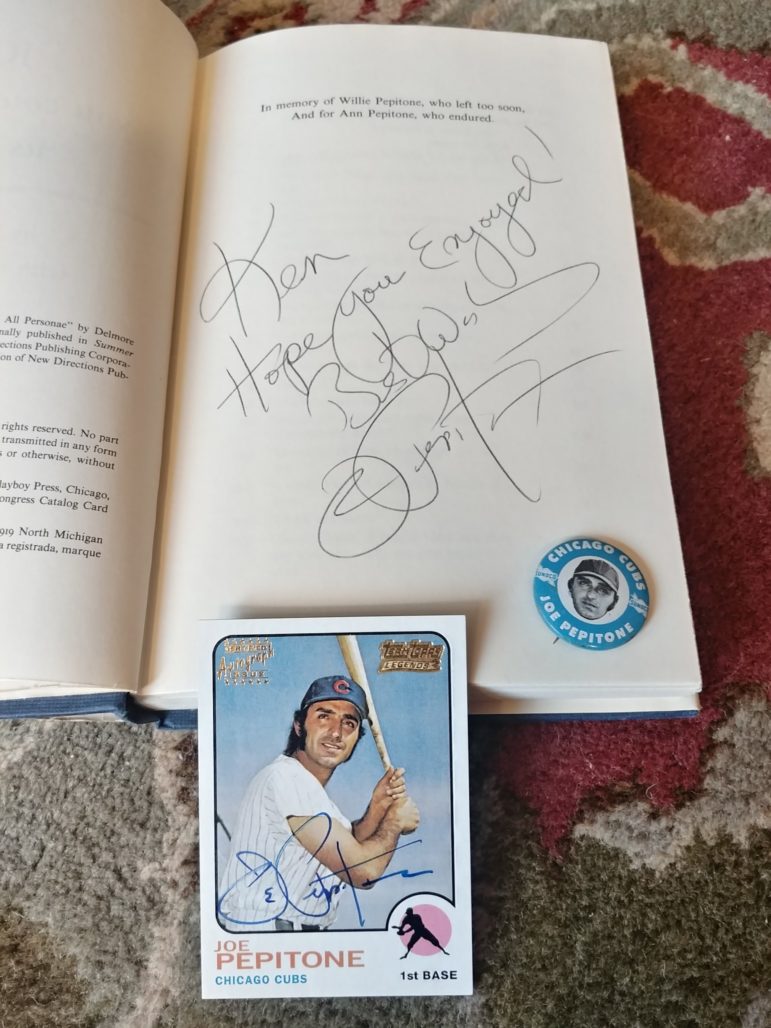

Signed dedication page of Joe, You Coulda Made Us Proud, autographed 2001 Topps baseball card of Pepitone as a Cub, and 1969 Cubs button of Pepitone [Photo by K. Seigfried]

Weeks later, he’s begging to come back and goes on to play a mediocre season. His lounge comes under police investigation in a drug probe, loses its customers, and shuts down. The Cubs have had enough and trade him to the Braves. He soon decides he’s fed up and quits major league baseball for good. A brief gig playing in Japan goes terribly, and then it’s all over.

Joe ends his book with an attempt to figure out what went wrong in his career and in his life. He reveals that nearly every night of his life, beginning with the night his father died, has been filled with “gory, grisly, violent, vicious” nightmares. The beginnings of his personal problems are clear, he writes,

But I don’t understand why I extended the bullshit for so long, why I had to put myself through so much grief for so many years without making some changes. I guess I was too screwed up to change, so I kept turning the screw deeper and deeper . . .

His children have grown up without knowing him. His days of playing baseball are over, and he’s still in debt. The mobsters from the Yankee days tell him he’s let down Italian-Americans as a whole, hence the book’s title. Another attempt to start a business sputters out. A newly rented house burns down.

Joe valiantly attempts to end the book on a high note, insisting that being with his third wife is all that matters. But more darkness was to come.

A year after the book was published, he attempted a comeback in the AAA Pacific Coast league that only lasted thirteen games. The Yankees brought him back as a coach in the early 1980s, but he was arrested in 1985 when police found large amounts of cocaine, heroin, Quaaludes, cocaine paraphernalia, records of drug transactions, and a loaded gun in a car with Pepitone. He was sentenced to six months in prison. This was followed by arrests for public brawling and for a spectacular 1995 DUI accident in the Queens-Midtown Tunnel. He eventually separated from his third wife.

Finally, at nearly eighty, he found some relief via psychiatric therapy. Diagnosed as bipolar, he claims to have been sober since 2000 and to have rebuilt relationships with two of his wives and three of his children. In 2015, he said that he still has vivid waking flashbacks about his father’s violence against him and his own actions toward his wives, but he now lives “a very normal life.”

Responding to abuse and the role of Pagan clergy

Such is the long shadow of abuse. Violence in the 1940s stretches its clutching hand into the second decade of the twenty-first century even as it spirals out to affect an increasing number of lives.

As painful as Joe Pepitone’s story is to read, it can be a meaningful learning experience for the wider Pagan community – especially for those of us who serve in the clergy or other leadership roles.

More frequently than we like to admit, dark tales of abuse burst out of Druid, Heathen, Wiccan, and other Pagan organizations. A member of the clergy has been abusing those who come to him for counseling. A ritual leader has been abusing followers under the guise of spiritual initiation. A congregation member has been stalking and harassing women in the group. When enough people begin to speak publicly, the news is carried by Pagan media such as The Wild Hunt. When shocking enough, the reports are amplified by corporate media.

Inevitably, there are reactions from Pagans that generally fit into three categories.

Everybody knew this was going on. This is usually the response from those looking for internet clout by acting as if they know more than others about what’s really happening on whatever Pagan sub-scene is in the spotlight. UK boxing columnist Steve Bunce calls these sorts of folks “after-timers,” meaning that – after the story is out – they pose as experts who knew it all along. The obvious question is if everyone knew about the abuse, why didn’t they speak out earlier and do everything necessary to protect the victims from further harm?

The group is fundamentally positive and this was just a bad apple. This response comes from those who are invested in the specific community for a multitude of reasons, and who are unwilling to jettison the relationships or status they have built up in it. The abuser is shunned, excluded, banned, and generally portrayed as a non-entity who doesn’t reflect the values of the group – even when the abuser has been a long-time leader or the actual founder. The dismissal of the abuser as an aberration can have the unfortunate effect of leaving all the mechanisms of abuse fully in place.

This group is fundamentally corrupt and everyone should quit. This is often the response of the victims of abuse and those who stand by them. Sometimes, the victims quietly leave the group to avoid denunciation by the loyal troops as slanderers of leadership. It’s only when victims or their advocates begin to forcefully speak out that the abuse is publicly addressed by the group or covered in the media. This, of course, is a heavy load to place upon those who have already had much put upon them. The true nature of the organization can be seen in how it, as a whole, responds to revealed abuse and what real actions it takes.

Pepitone’s book can teach us several things.

It can be simultaneously true that everyone knows what is going on and no one will or can do anything to stop the abuse or its consequences. Within his extended family, who can young Joe turn to for protection from his father’s violent wrath? His mother, uncles, and everyone else is scared to place themselves in the path of Willie’s anger. Today, how many who know of abuse within their Pagan organizations are willing to publicly announce it, report it to the media, or contact law enforcement? Whisper campaigns, righteous tsk-tsking, and subtweeting in online forums may make the witness feel like they’re standing against the abuse, but they do almost nothing to stop the abuse or help the victims.

The “bad apple” concept manifests in both the deluded self-understanding of the individual and the distancing censure by the group. Pepitone simultaneously builds walls around the lasting pain of his childhood abuse and the unpleasant actions he himself takes in response to that pain. He both understands his father was a deeply troubled man who committed horrific acts of abuse and knows that he deeply loved his father as a role model and granter of approval. So much of Joe’s out-of-control behavior with parties, alcohol, sex, and drugs is to separate and bury the knowledge that his father repeatedly and intensely beat him – to recontextualize those beatings as merely things that his father did and not fundamental aspects of who his father was. Ditto for Joe’s own acting out; he repeatedly emphasizes how much he loves his wives and children, how his decades of nightly infidelity really meant nothing next to the feelings he had for his family. Such is the logic of the “bad apple” in Pagan organizations. The fact that an abuser has used the group as a happy hunting ground, sometimes as a leader or with full knowledge of leadership, is walled off to deny the depth of rot in the community.

Full condemnation of self and group is the most difficult path of all. For Pepitone, to admit that his foul treatment of his wives and his functional abandonment of his children is, in fact, parallel to the psychological abuse his father subjected him to after the near-blinding is simply too much. It would make him as bad as his father at his worst moments, so he throws himself ever deeper into means of escape in order to avoid this line of thinking.

For organization members, to denounce the group as basically flawed and unsalvageable is to admit their own culpability in supporting a system that allowed the abuse and protected the abuser.

For the individual, the best path can be full removal from the situation and a commitment to serious therapy and treatment.

For the group, full acceptance of responsibility is sometimes best served by the total dissolution of the organization. This sort of reflective honesty is not easy, to say the least.

As clergy, we must work to build our own understanding of these issues in order to help the victims of abuse, even when those victims themselves have become the abusers. Pepitone’s story shows us that the line between victim and abuser can be almost invisible. How do we both do right by a truly suffering victim of abuse such as Pepitone and fully stop further actions of abuse by a determined perpetrator such as Pepitone?

Too often, Pagan clergy have let their understanding of the cycle of abuse sway their sympathies overly much to the side of the abuser who is acting out the pain of their own past suffering. Yes, Pepitone was treated absolutely horrifically by his father. No, this does not justify the way he treated the women and children in his life. How often have we heard of Pagan leaders circling the wagons to protect an abuser? How often has their understanding of the complications of the abuser’s own situation blinded them to the damage that the person was doing to others? Much is at play here, not the least of which is the tendency to privilege men’s internal conflicts over the overt damage done to women.

When it is true that the abuser is acting out as a consequence of their own abuse, yes, we should be sympathetic and offer all the help we can. But the first step must always be to ensure that the abuser has absolutely no pathway to abuse others. The bodies, minds, and spirits of the victims are not a playground for the abuser to work out their own issues. That must be the baseline upon which further clergy actions are taken. Unfortunately, the instinct can be to prioritize the protection of the abuser, to keep them from embarrassment, and to stop the wider world from finding out what has been happening within the group. This tendency towards secrecy, even when supposedly taken for the privacy of the victims, can be driven more by a desire to keep the organization from losing members and attracting negative public attention. The unfortunate result of this veil-drawing can be a continuation of the abuser’s harmful actions in the shadows.

Pagan clergy must become familiar with a variety of local resources. We must know how to confer with and recommend mental health professionals, crisis hotlines, abuse shelters, and specific offices within law enforcement. When Pepitone opens up about the things that did help him in either the short or long run, he cites both psychiatric care and deep conversations with his close friends and family members. We must build a sense of when it is time to put someone in contact with specialist professionals and when it is helpful to engage as active listeners and spiritual counselors. There are times when medical intervention is clearly needed, there are times when legal consequences are required, and there are times when pastoral care is paramount. These methodologies should work hand in hand to create a helpful and healing environment for all involved.

Pagan clergy have unique knowledge and skills. They know the mythological, literary, historical, and archaeological backstory of their tradition. They lead specific rites with specific ritual practices throughout the wheel of the religious year. They also need skills that are not so unique but that are common to clergy across unrelated religious traditions. The ability to deal immediately and deeply with instances and histories of abuse is one of them.

Whether through personal study, continuing education courses, or focused workshops, even long-established Pagan clergy can strengthen their understanding of the issues and their own role in addressing them. Sometimes, it is best to step aside and let a variety of professionals do what they do best. But we must also make sure that we have the skills to step up at the times when the clergyperson is the one upon whom the responsibility falls and the one from whom guidance and decisive action are needed.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.