I have a tendency to fall in love with places I have never seen. I don’t think this is unusual; many of us have seen a place in a photograph or a film and found ourselves struck with a longing to see it in person. Sometimes I have pined for a location for many years: I fell in love with the columns of Durham Cathedral in the United Kingdom when I was 18 years old, and nursed that longing for 12 years before I could actually reach out my hand to touch them. This yearning is deep magic for me – the kind of magic that sometimes takes hold of my life and guides it along unforeseen paths.

Earlier this week, The Wild Hunt‘s Sean McShee reported on the Harvard Celtic Colloquium and the new research on medieval Irish manuscripts presented there. As I read the article, I found my mind drifting toward another one of those dreamlands I have fixated on: Station Island, located in Lough Derg in County Donegal, Ireland, the site of a Catholic pilgrimage called St. Patrick’s Purgatory.

The chapel on Station Island, overlooking the “beds” of the saints: stone circles with a cross in the center [Egardiner0, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

I first read about St. Patrick’s Purgatory in a seminar on pilgrimages I took during graduate school – it is the subject of a chapter in Edith and Victor Turner’s Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture, a book whose influence on me I have written about elsewhere. According to the legend of the practice, St. Patrick prayed to his god that, in order to convert the Irish, he needed to be able to show them proof of the afterlife, and especially of the dangers of Hell and Purgatory. His god then revealed to St. Patrick a cave on Station Island where St. Patrick saw Purgatory for himself and could demonstrate the same to any reluctant pagans. (The Turners note that finding Purgatory inside of a cave is likely a holdover from pagan traditions, in which caves frequently bear connections to the afterlife.)

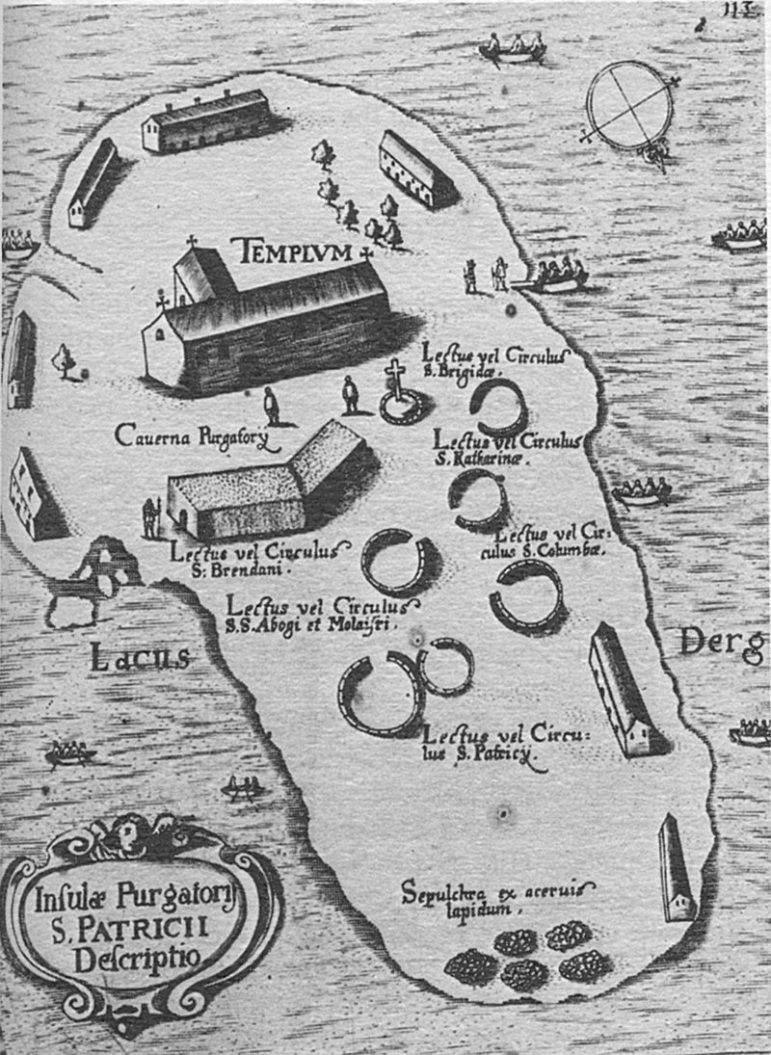

The Turners used Station Island as their example of an “archaic” pilgrimage, one where the current practice seems to reflect a survival of a previous religious form. The theory was intriguing to me, but I was more interested in their description of the ritual practice on the island. Once pilgrims arrive at Station Island, they engage in three days of almost continuous and circuitous prayer, with barely any sleep and only a little food. The ritual revolves around a series of stations – hence the name – that dot the island, including a set of stone circles that are believed to be the remnants of beehive cells that monks once lived in. These stations are each dedicated to particular saints, including many distinctively Irish ones – St. Brigid is among them. A circuit of the stations takes about an hour and 15 minutes to complete, and over the course of the three days a pilgrim is on the island, nine are required.

Four of those circuits, however, take place during a vigil in the Basilica of St. Patrick, in which the priests lead the pilgrims through the stations of the cross throughout the course of a sleepless night. Hundreds and hundreds of Our Fathers and Hail Marys and Apostles’ Creeds are intoned over the course of that night, as the pilgrims attempt to fight off the urge to sleep. (In the past, if a pilgrim fell asleep, they were said to be in danger of being damned to hell; today, they merely lose their chance for indulgences, which are already an archaic notion to most Catholics.)

Now, many readers may read that description and think to themselves, “that sounds horrible,” and I could not blame them for feeling that way. Certainly, St. Patrick’s Purgatory sounds like an ordeal – both in the modern and the classical sense of the term. But to me, anyway, it also sounds like an incredible ritual experience, the kind of thing that, if entered into with a willing heart, could put a participant into a communion with the divine that would not be possible through less arduous means. Certainly, the poet Seamus Heaney, one of my heroes, thought so; his long poem “Station Island” was inspired by his own journeys to the Purgatory.

A map of Station Island from 1666 by Thomas Carve [public domain]

I have often thought of what a ritual like this might look like for modern Pagans. I am reminded of the Vision Quest ritual that I participated in for many years at the Heartland Pagan Festival at the Gaea Retreat, which also involves making a journey through a number of stations. I toy with the idea of something that involves a similar kind of path through shrines and altars over the course of days – something that requires resilience and dedication to complete, and with a similar focus on repetition and devotion, a ritual action done again and again so often that it becomes encoded in the rhythm of breathing.

There is a part of me that thinks of this and then thinks of all who would be left out – it is a form of ritual that assumes one’s body is “able” in a way many are not, including sometimes my own, and just because that is not an issue for the Irish pilgrims does not mean it should not be an issue for us. The logistics of how to have such a pilgrimage be both welcoming and challenging are formidable. But it strikes me as something worth doing, which is why every so often I open my notebook and scribble down new notes for how it might be accomplished.

I have not yet visited St. Patrick’s Purgatory myself, although they do note that pilgrims of all faiths are welcome there; I hope to see it someday, just as I saw the columns at Durham Cathedral. Until then, I will have to do my stations in pen and ink.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.