TWH – In early October, the Harvard Celtic Studies Department presented two events. The 17th John V. Kelleher Lecture and the 40th Annual Harvard Celtic Colloquium. The Celtic Colloquium took place from October 8th to 10th.

Two topics presented for discussion would likely be of interest for modern Pagans.

First, what was the context for the production of medieval Irish manuscripts? Those manuscripts provide most of what we know of ancient Irish mythology. Second, how was Irish folklore collected in the 1930s? In that project, schoolchildren collected a massive amount of folklore.

A scholarly perspective can help provide context for medieval Irish manuscripts. In the Medieval period, books were not a mass-produced commodity. Patrons would commission someone to write a new book or a scribe to copy an old book. Without moveable type, scribes would laboriously write the book by hand. Scholars can explain what the manuscript meant to the patron. They can also examine how that meaning affected the content of the work.

No one would describe ancient or medieval Ireland as an egalitarian society. It had a definite hierarchy ranging from petty chieftains to high kings.

“Ancestors, Gods and Genealogies”

On October 7, Professor Ruairi Ó hUiginn of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies gave the 17th John V. Kelleher Lecture, “Ancestors, Gods and Genealogies.”

Genealogies form a distinct category of medieval Irish manuscripts. Unlike other manuscripts, most genealogies remain untranslated. Many genealogies contain material that explained power relationships among powerful Irish families and also contain the origin stories of those families. Mixed in with the genealogies are praise poems and other poetry.

These manuscripts reflect their times. They link those powerful families with powerful ancestors from the Judeo-Christian tradition. The “Book of Invasions” has a similar technique. It links people from myths of the settlement of Ireland to people from the myths of Noah’s flood.

The Duanaire

Emmett de Barra of Trinity College Dublin spoke about the Duanaire. He said that Duanaire has two meanings. According to one meaning, a Duanaire creates or performs poetry. In the other meaning, the poet or presenter creates Duanaire. In the second meaning, Duanaire referred to a songbook, poem-book, or anthology of poems. In this family material, the praise-poems could offer praise to one person or to their ancestors.

To understand the Duanaire, it is necessary to understand the people who wrote them. The filid (professional poets) wrote Duanaire. According to the online Encyclopedia Britannica, “After the Christianization of Ireland in the 5th century, filid assumed the poetic function of the outlawed Druids, the powerful class of learned men of the pagan Celts.”

In contemporary terms, praise-poems combined a legal argument about legitimacy with a nominating speech from a political convention. They also reiterated and enforced the values of the Irish elite in that period.

De Barra argued that praise-poems functioned to provide legitimacy to a specific ruler. More broadly, the filid legitimatized the Irish nobility. Duanaire was critical to this legitimization.

The opposite of a praise-poem would be a satire of the noble. If de Barra’s interpretation is true, then a filid’s satire could delegitimize the power of the chieftain. It would also challenge his authority. More crudely, it could invite the chieftain’s rivals to topple him and seize the chieftaincy. That would be consistent with the fear that a filid’s satire could produce in a chieftain. Those poets had “clout.”

The Book of Fermoy and The Book of Lismore

Tatiana Shingurova of the University of Aberdeen spoke about two books. She said these two books contained a history of two, interconnected, noble Hiberno-Norman families, the Roches, and the FitzGeralds, who intermarried.

Their interrelationships are documented in The Book of Fermoy and The Book of Lismore. Both the Roches and the FitzGeralds had an interest in preserving Gaelic culture.

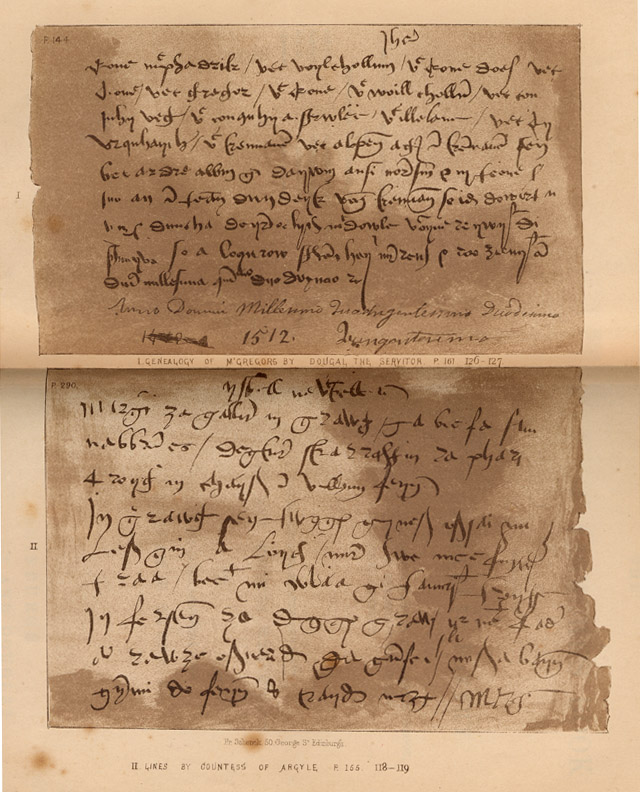

Image credit: Uknown; Rev. Thomas McLoughlan; William F. Skene. – The Dean of Lismore’s book: a selection of ancient Gaelic poetry from a manuscript collection made by Sir James M’Gregor, Dean of Lismore, at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Public Domain

Both books share similar content, style. The same scribe appears to have written both. The Book of Lismore was written in South Munster between 1450 and 1500. The Book of Fermoy was written between 1467 and 1561.

The Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in Royal Irish Academy lists the contents of The Book of Fermoy. To modern eyes, it does not resemble a book. It looks more like the contents of a poorly organized filing cabinet. Some parts of the original may have failed to survive. That could explain its disorganized appearance.

The Book of Fermoy does contain a great deal about the Roches and the FitzGeralds. It contains parts of the Book of Invasions. It also contains a great deal of Christian material such as Gospel history and extracts from Church fathers. In addition, it contains a few medical texts. Intriguingly, it contains the “Story of the man who became a woman.”

These medieval manuscripts gave modern Pagans what we know of ancient and polytheistic Ireland. Understanding them is not simple.

Irish schoolchildren collect folklore

Nikita Koptev of the National University of Ireland, Galway, discussed the collection of folklore by Irish schoolchildren, aged 11 to 14. Some older children also participated. From 1937 to 1938, 50,000 students collected 740,000 pages of folklore. This collection took place in the 26-counties of the Republic of Ireland.

The students collected and wrote this folklore in English, Irish, or both languages. This massive effort to collect living folklore occurred as Ireland was modernizing. Note: It is not clear if a similar collection occurred in the six counties of Northern Ireland. If not, the folklore of Ulster would be under-represented in this collection.

Koptev described the process. Students would write down the stories. Then, they would submit them to their teacher. Teachers also collected a few stories. If several stories were similar, the teacher would select the best. They did this to avoid repetition. Adult cooperation proved essential.

The types of folklore collected included riddles, children’s games, folklore about their home district, Holy Wells, butter churning, “the wee folk,” and caring for farm animals.

When students collected folklore, it differed from that collected by adults. Students’ stories tended to be shorter. School children used less elaborate dialogue. They also used fewer fillers and additives than adults did.

This material has already been transcribed but has yet to be digitalized.

If anyone wants to learn more about a scholarly perspective on Celtic culture, they should visit Mahindra Humanities Center Seminars on Celtic Literature and Culture.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.