Over the last 18 months, the rising popular interest in Witchcraft has not gone unnoticed by many of us. Just this week, Daniel Zomparelli, fiction author and editor of Poetry is Dead, proclaimed in The Cut that the pandemic had turned him into a Witch. “Here’s the thing about doing spellwork,” he writes. “The process forces me to take note of where I am, what I want, and where I want to go. It grounds me in a way that makes me feel connected to a world that I can sometimes feel outside of.”

The gamut of topics covered as Witchcraft, from rituals and spellcasting to healing and tarot, continues to gain attention on TikTok. As CNN wrote last week, “The TikTok community in which such rituals thrive goes by many names: ‘WitchTok,’ ‘SpiritualTikTok,’ ‘AstrologyTikTok.’ These names are a shorthand of sorts, as the practices shared among followers originate from a multitude of religions, philosophies or cultural backgrounds. As a whole, they are united by a fascination with the unknown, and the unknowable.”

This popular interest in occult topics and Witchcraft has been mirrored by a steady resurgence of interest in mystical and spiritual artwork. Earlier this year, The Wild Hunt covered the renewed interest in the work of Remedios Varo. As noted there, The Guardian had already observed noteworthy general attention to occult arts, commenting that popular culture had been growing “a bit witchy” for a few years, but that a more serious engagement with occultism in arts and culture had happened recently. “Rather than the hipster witchery of a few years ago,” writer Hettie Judah noted, “this new spirituality is rooted in explorations of feminism, anti-colonialism, and alternative power structures.”

Leonora Carrington [Fair Use]

Long before the current interest in occultism and mysticism as a countervalent to patriarchy, Surrealist painter and author Leonora Carrington had been using witch imagery and occultism to dismantle power and chauvinism.

Carrington was an artistic colleague of Remedios Varo, and as that close friendship grew, so did Carrington’s interest in alchemy, Kabbalah and Popul Vuh, a text recounting the history of one of the Mayan peoples that included the sacred stories of their creation, heroes, and founding.

Carrington was born to an upper-class Irish-Catholic family in Lancashire, England, at the end of World War I. But her non-conformity quickly drew the ire of her tutors, nuns, and governesses, and then finally her father, a wealthy textile merchant. Her “rebelliousness” saw her sent to Florence, Italy, where at the age of 10 she was first exposed to Surrealism during a trip to Paris. Her interest in art grew, though her father immediately opposed it.

via #WOMENSART on Twitter

Her father wanted her to be a debutante, an idea she would instead use as the title of a short story in her collection The Oval Room. By her twenties, her father had her committed to a Spanish mental institution, just as the Nazi occupation was taking hold across Europe. “Of the two,” she wrote, “I was far more afraid of my father than I was of Hitler.”

In the late 1930s, she had an affair with German surrealist Max Ernst at the International Surrealist Exhibition, but she fled from Nazi occupation, ultimately to Mexico City where she remained for the rest of her life. Through Surrealism and its juxtapositions and abrupt contrasts, and her longstanding interest in the natural world, especially animals, she would learn to dissect human follies.

In her 1944 memoir Down Below, Carrington wrote about how her lens on humans had been shaped by human madness. In the opening text, she extends an invitation:

Exactly three years ago, I was interned in Dr. Morales’s sanatorium in Santander, Spain, Dr. Pardo, of Madrid, and the British Consul having pronounced me incurably insane. Since I fortuitously met you, whom I consider the most clear-sighted of all, I began gathering a week ago the threads which might have led me across the initial border of Knowledge. I must live through that experience all over again, because, by doing so, I believe that I may be of use to you, just as I believe that you will be of help in my journey beyond that frontier by keeping me lucid and by enabling me to put on and to take off at will the mask which will be my shield against the hostility of Conformism.

During her forced institutionalization in unsanitary conditions, Carrington would experience ruthless therapeutic interventions, sexual assault, and medical experimentation. The experience would forever reveal how power structures will insatiably seek to maintain the status quo. Peter Campbell of London Review of Books wrote that “while other Surrealists played at madness, she was intimate with it.”

Carrington’s first major painting was just a few years earlier: The Inn of the Dawn Horse (Self-Portrait) [1939, oil on canvas]. The painting depicts her sitting on a blue throne with a wild crown of hair in a corner of a room, with a floating hobby rocking horse, a lactating hyena, and a window framed by elegant draperies through which is seen a horse running in a field. The painting is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

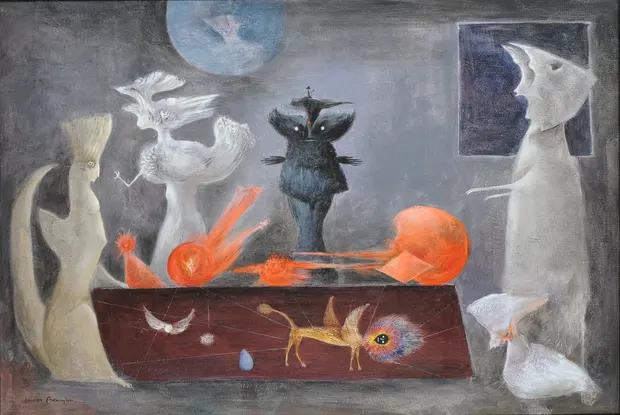

Evening Conference, 1949. Photograph: via Estate of Leonora Carrington [Courtesy]

The painting explores the idea of freedom, but it also had a mythological bent. As Artland notes, “Her interest in Celtic mythology, from her childhood nanny, would mean that Carrington was familiar with the Celtic goddess Epona, goddess of fertility.” The female hyena evokes raw power and wildness, themes that would persist in her work. Critic Janet Lyon would observe that in Carrington’s works, “the appearance of an ordinary human always feels like an aberration, a harbinger of death.”

Carrington would be a life-long advocate that female sexuality must be illustrated as experienced by women, not through the needs or fantasies of men or the male gaze. She would often portray feminine figures in ironic stances.

In Mexico, Carrington would cultivate her interest in Mexican traditions, folklore, and the stories of Indigenous peoples. In 1964, she unveiled a mural, “El mundo mágico de los mayas” (the magical world of the Maya) at Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Antropología (National Museum of Anthropology). The monumental painting shows her reverence for Mayan culture and the scientific knowledge available at the time of its drawing. Yet she maintains her Surrealist roots in a masterpiece that is both visually and culturally complex.

“El mundo mágico de los mayas” de Leonora Carrington [Courtesy : Museo Nacional de Antropología]

Carrington’s commitment to emancipation would also permeate her artistic works and her political life. She would tackle gender identity, aging, and body shaming in her 2004 book The Hearing Trumpet. “Carrington leans into her starkest eccentricities, depicting the subversive power of womanhood with more imaginative zeal than almost any other 20th Century novelist,” wrote Brady Brickner-Wood in Ploughshares. Regrettably, some of her book’s narrative, to a modern Queer reader, is disappointingly dated.

Like Varo, Carrington rebelled against the rampant misogyny in society. She was a founding member of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico during the 1970s. In 1972 Carrington designed mujeres conciencia (“women’s’ consciousness”), a poster for the movement depicting the expulsion from the Garden from Genesis. Like that story, the poster shows a serpent and a tree with two female figures exchanging the fruits of the Tree of Knowledge. In this depiction, Adam is nowhere to be seen.

Carrington died ten years ago in Mexico City at the age of 94. Her mystical piece The Juggler hallmarks her fusion of Surrealism and, at the time of auction in 2008, reportedly garnered the second-highest sale price for a living Surrealist Painter, of whom she was the last.

Interest in her work continues to rise and a new generation is discovering and uncovering Carrington’s subtle use of imagery that echoes the divine feminine with obviously Pagan themes while inviting all of us to ignore the patriarchy and re-wild ourselves.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.